🎨😢 The algorithm doesn't care about your art

Navigating the landscape of social media feeds with Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld

We’re hiring a Senior Software Engineer for our Public Spaces Incubator! Learn more and apply here.

Join Plurality Institute and The Council for Tech and Social Cohesion for a symposium on comment section R&D at the Internet Archive in San Francisco on May 2.

“The way that art is made and distributed now is not how it was for the past few centuries,” writes New Yorker columnist Kyle Chayka in his new book Filterworld. Now, everything is different:

There was no constant heckling from an audience in a quiet studio or workshop or at a writing desk. Innovation came not from adaptation to a metric of constant engagement but in creative leaps that might have been shocking at first glance. When you conform to expectations too much in advance or rearrange your imagination to fit a particular set of variables, it can mean that leap is denatured or cut short. That’s bad for both artists and consumers.

After reading Filterworld, I think Chakya has a lot to say about the way ranking algorithms and recommendation engines have reshaped our lives, our culture, and the world we live in. He also charts this shift’s causes, its many consequences, and what might be done to change it.

While the book contains a lot of commentary on music, visual art, and even poetry, it also goes deep on how algorithms work and their ripple effects throughout society. The weekend after President Biden signed a bill forcing the sale of TikTok, considering the power of these feeds could not be more salient.

This is a key topic for anyone building or maintaining a digital platform or online community. It’s important to appreciate different ways in which the design features of our digital spaces can affect us, in both small and profound ways. Let’s dive into my book report of Filterworld.

Welcome to Filterworld

Chayka places our contemporary social media feeds in the context of ongoing technological change. Ranking feeds essentially sort content and decide what should be on top. This has been an important part of the internet since the beginning: Xerox PARC engineers wrote programs to filter their emails in 1992, and Google’s founders started work on PageRank back in 1996. As social media spread, Facebook introduced the News Feed in 2006. It's worth remembering why the “like” button exists at all: it’s a powerful signal for ranking.

But Chayka marks an important turn towards our “filterworld” in the last decade — Instagram and Twitter’s switch from chronological feeds to algorithmically-sorted ones, and the launch of TikTok and its powerful For You Feed. Now, large language AI models join this lineage, with incredible powers to sort language and evaluate quality.

From TikTok to Spotify, algorithmic feeds are everywhere — they’re the cultural water we all swim in. “The dragnet is inescapable,” writes Chayka. He argues that these feeds are not neutral. According to Chayka, algorithms not only push us towards popular content, they have a sort of flattening effect. By optimizing for engagement, many social media feeds push us towards pieces of culture that are more Western, ambient, empty, cheap, and ephemeral.

“The perfect piece of algorithmic culture, after all, is almost intentionally uninteresting,” writes Chayka. In identifying the sameness of art meant for global, universal appeal and amplification, Chayka invokes pieces as varied as Lofi Girl and Marvel movies.

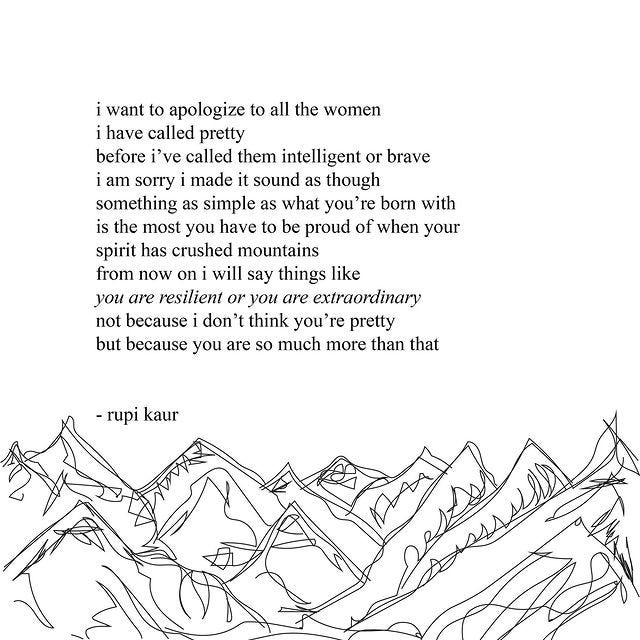

Indeed, artists and influencers are constantly anticipating the preferences of social algorithms and adapting accordingly. Musicians are writing shorter pop songs. Poets are even optimizing their stanzas and couplets to go viral on Instagram. Chayka argues that while deeply challenging works of art can still emerge, the overall cultural landscape is shaped by algorithms, which promote “passive, frictionless consumption.” Chayka writes, “Ultimately, the algorithmic feed may not be the death of art, but it often presents an impediment to it.”

Chayka also notes that often, platforms foster an illusion of endless diverse options. YouTube and Netflix might seem like they have unlimited libraries. But only a small percentage of YouTube videos have even hundreds of views, and according to Chakya, Netflix hosts fewer titles than the average Blockbuster franchise once did.

Living amongst the algorithms

Beyond the content itself, Chayka says that platform algorithms foster certain unusual behaviors and emotions, both from people who create and post about culture, as well as those who experience it.

For those of us scrolling through our feeds, Chayka identifies “algorithmic anxiety,” a modern phenomenon of having to “constantly contend with automated technological processes beyond our understanding and control.” And for those posting content, Chayka cites a “double negotiation” of having to please both an unknown, massive audience of strangers as well as the algorithm.

Crucially, Chayka argues that social media’s algorithmic feeds run counter to the qualities required to form personal taste, learn new things, and form community. He advocates for the mutual learning that happens in fan culture, as well as carving out the time and space to develop taste. It’s much harder, he says, to become a connoisseur of anything through TikTok. And even worse, the algorithm suggests that you might not even need your own personal taste anymore.

Chayka illustrates his book with examples from his own life. As a millennial around his age, there’s plenty I connected with personally, including building websites on the early web and joining Facebook as it began. (We also know each other from when we were both freelance writers in D.C.) Through blogging, tweeting, and eventually trying an algorithm “cleanse,” Kyle’s experiences add a welcome richness, humility, and levity.

Chayka also argues feeds are flattening and homogenizing culture throughout the world. Here, I think he maybe overreaches a bit. Feeds may spread cultural ideas everywhere, but not evenly or uniformly. In a year of traveling Asia, I went to many places that have most American social media apps, but not Western-style AirSpace Airbnbs. By emphasizing coffee shops in Iceland that remind him of home, Chayka risks overly generalizing and simplifying the world, much of which remains mind-numbingly diverse, surprising, and unflattened.

Similarly, Chayka makes the case for Instagram supercharging certain kinds of international tourism. The photo-sharing app has undoubtedly shaped contemporary travel, it is hard to sort out causation: Are people taking more photos now because they have smartphones, or because they want to post on Instagram? Obviously both are true.

So what do we do?

Longtime readers of this newsletter will be familiar with many of the regulatory and policy ideas Chayka explores in Filterworld. He has a strong grasp on potential solutions to the excesses of algorithms, and confidently explains some of the largest hurdles to reform, including monopolization, Section 230, and the capitalist "growth-at-all-costs mindset."

Chayka highlights the efforts of experts we enthusiastically support, including Nate Persily’s focus on transparency and Daphne Keller’s advocacy for limiting viral amplification. He also shares our high hopes for meaningful European legislation.

But Chayka is most passionate in favor of greater agency and curation. “We users are what makes social media run,” he writes, “and yet we also aren’t given full control over the relationships we develop on the platforms, in large part because algorithmic recommendations are so dominant.”

Even though there are only a few companies running these platforms, Chayka reminds us that we can walk away, as many have from Twitter/X. Alternatively, we can choose to support — with our time, attention, and money — the people and platforms doing it right. This concept came up in my conversation with Sari Azout from Sublime, and Bluesky CEO Jay Graber has also elevated the idea of “algorithmic choice.”

For Chayka, doing it right means cultural stewardship, or curation. With examples like art curators and independent radio DJs, Chayka shows that curation isn’t just deciding where on the wall to put the painting. It actually often requires “hundreds of hours of research, writing, thinking, and maintenance," he writes.

Chayka argues strongly for experienced, creative, and considered curation over recommendation feeds. I thought immediately of Jason Kottke, who has been blogging for decades, building up an intricate canon of his own recommended links. I know that I like a lot of what he blogs about, and even if I don’t like it, it’s usually interesting enough that I’m glad I’ve seen it. I happily support him with my yearly membership. But bloggers like Kottke are few and far between. Chayka is on to something:

The internet might have an overflow of curation, but it also doesn't have enough of it, in the sense of long-term stewardship, organization, and contextualization of content — all processes that have been outsourced to algorithms.

Chayka longs for the social web to have the freedom, individuality, and customization of early web hosts like Geocities. He also gives plaudits to small but sustainable streaming efforts, like the Criterion Channel and classical music app IDAGIO. Chayka recognizes that not all culture needs to be highbrow, and he recognizes that even the mind-numbing passivity of TikTok’s feed has a place. It just shouldn’t be every option, everywhere.

He ends on a somewhat circumspect note, offering that generative AI might be about to supercharge the flattening of culture. Already, AI images trend towards a superficial, stereotypical glossiness. And where calling something “algorithmic” has been shorthand for cheap and slick, “AI-generated” is coming to mean something similar.

Chayka, at least, is trying to lead by example. In addition to his writing at New Yorker, he has also started indie publishing projects like Dirt, and more recently, One Thing, a newsletter of cultural recommendations, one at a time.

Sound off in the comments: Who are your favorite non-algorithmic cultural curators?

Thrilled to have assistance from Haoshu, our new Communications Fellow,

–Josh