📕 Overdue, Part 1: the birth of public libraries

Franklin, the library movement, and the start of free, public libraries

This week, we kick off our first two-parter on library-building in the US, from Franklin through Carnegie.

In most American towns, suburbs, and cities, there’s usually a library where you can borrow books, use the internet, or simply rest safely for a while. And while they aren’t perfect (more on the current state of libraries next week), libraries are still striving to be what steel magnate Andrew Carnegie called “palaces for the people.”

“Palaces for the people” is actually the title of the 2018 book by sociologist, author and New_ Public Advisory Board member Eric Klinenberg. Here’s how he described libraries to us in 2020:

The library as a built structure really dignifies people who come in to use it, there's something about walking into a library where you feel the generosity of the building and of the people that support it. The library lifts you up because when you feel dignified by a place, when you feel welcome there, when you feel like the place is going to teach you generously and recognize your humanity—that really encourages you to be the best version of yourself.

From the beginning of New_ Public, we’ve been asking ourselves: what would a public library look like on the internet? We are sincerely hopeful that something like this is possible. But who will advocate for this effort, and who will fund it? This week and next week we’ll be returning to the public library, and examining a crucial turning point in its history.

In 1886, there were 600 public libraries in the United States. By 1929, Andrew Carnegie had funded the construction of 1,679 more. This change had a tremendous impact, and built what Eric describes as a social infrastructure that we still rely on today.

What was the library movement? How did Carnegie dramatically expand on its vision? Who was left out? What responsibility do the mega rich have in investing in social infrastructure, and what can we learn from Carnegie’s example?

Let’s take it back, way back, to Benjamin Franklin and the post-revolutionary era:

🕦🕚🕥🕙🕤🕘🕣🕗🕢🕖🕡🕕🕠🕔🕟🕓🕞🕒🕝🕑🕜🕐🕧🕛🕦🕚🕥🕙

Mr. Electricity

Famously an inventor and a founding father of the United States, Ben Franklin was also incredibly wealthy.1 A printer, Franklin valued books tremendously, and any history of libraries in the US often begins with him. In 1731 he founded the colonies’ first membership library, the Library Company. Paying members could borrow books freely, but non-members would have to leave a deposit in order to borrow.

In Massachusetts, the town of Franklin asked their namesake for a donation, hoping for a bell. However Franklin opted to send them a collection of books instead and start a library.

These two examples are representative of a larger trend: throughout the nation’s first century, many libraries would be private, members only organizations, and nearly all libraries were subject to the private benevolences of wealthy individuals. Also, women, people of color, and books of popular fiction were not necessarily welcome in most libraries yet.

1800-1850: Libraries spread

As an American middle class developed, there was rapid growth in cities. Immigrants and workers from rural areas were arriving in large numbers. According to The Library, an Illustrated History by Stuart A. P. Murray, a new movement for universal literacy and mandatory schooling was gaining momentum, tied to a nationalistic belief that democracy “required educated, informed citizens.”

Libraries started to spread to small towns and rural areas. Two years later, New York state passed an innovative law allowing school districts to raise taxes for school libraries. These new libraries would be school-administered, but also open to the public, including adults. This method of library-making spread throughout New England, where Murray writes that more than a thousand school libraries were established between 1800 and 1850.

1850-1900: A movement takes off

By the mid-19th century, the school library model was starting to crack a bit from the strain of inadequate and inconsistent funding. Many local public libraries popped up, but without regular funding, they couldn’t last.

Enter: the library movement. Many communities were eager for a library, and a growing chorus of academics and civil servants in America and parts of Europe was increasingly advocating for expansion. For example, there was Melvil Dewey, of the famous organizational system, who created New York’s “traveling libraries.” These were collections of 100 books that would rotate through library-less communities. “Traveling libraries, essential to their mission, began to appear in state after state, sometimes government-sponsored, sometimes private,” writes Murray.

I see a lot of parallels between the library movement and the contemporary chorus calling for a new generation of more responsible and ethical social media platforms. The men (and before long, women!) of the library movement had an evangelical fervor for building these new, public institutions. They believed that as opposed to private, pay-to-join libraries, it was only right that everyone have access to high quality information for their self-betterment. In the years after the Civil War, they saw a direct connection between libraries and democracy.

Between 1850 and 1900, the library movement celebrated many victories, including the formation of the American Library Association and the installation of a free public library in “virtually every large city,” according to Murray. The number of public libraries in the US soared during this time.

Growing pains

However, several significant stumbling blocks remained for the burgeoning American library system, some of which dated back to Franklin. Approaching the 20th century, public libraries were still dependent on private wealth to sustain them. Unlike with schools, many municipalities were not committed to supporting libraries consistently. Also, free public libraries were mostly in cities — smaller towns and rural communities couldn’t afford to build them, let alone buy books and pay staff. The library movement had plenty of enthusiasm, but it needed money.

Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-born founder of US Steel, arguably had the opposite problem. He had convinced himself that nothing was worse than “millionaires who died with their fortunes intact,” and if he wanted to live up to his values, he had a lot of money to give away. He soon found his niche: library-building. In the first years of the 1900s, Carnegie built a philanthropic machine so efficient that it was paying for new libraries every day of the year and giving away hundreds of millions of dollars in today’s money, with hardly any effort on his part.

Next week: how Carnegie did it. What was the full impact of his philanthropy, and what lessons can we apply to the growing movement for flourishing digital public spaces?

In this new feature, we’ll highlight a few tweets and then do something unusual — explain them in context. Stay tuned as this space evolves and changes!

Damon Beres, Editor and Chief at Unfinished Media, where we’re a network partner, has this quote from a Wall Street Journal article by Justin Scheck, Tom McGinty and Newley Purnell. As Beres notes in his tweet, this error of Facebook’s is “adding up to millions of dollars for Meta” because of the lucrative deals Facebook has made with cell companies. This is illustrative of a fundamental, recurring problem at Meta: not enough attention to users outside of the US.

Along the same lines, here’s Rest of World Photo Editor Cengiz Yar, highlighting a piece by Ramon Royandoyan about internet vending machines in Manilla, Philippines, called “pisonets.” Two companies, Globe and PLDT, have had a duopoly on internet connectivity for decades. These pisonet machines are in a legal gray area, and they fit into a larger Philippine practice of buying things as needed as opposed to in advance.

Hey, we’re on Twitter too! I wrote this tweet about Neil Young taking his music off Spotify in response to Covid misinformation, specifically Joe Rogan’s podcast, which Spotify owns. I’m spoofing the lyrics to “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue).” This fight with Spotify is only the latest chapter in Neil Young’s long, complicated history with streaming. It’s worth noting that you can still find pretty much any Young song on YouTube, a platform with arguably far worse Covid misinformation problems than Spotify.

Log Rolling

Three quick reminders for you:

Our book club is coming up, but you still have plenty of time to buy and read the book: Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore.

We have three job openings available: Head of Project, Community Architect, and Design Facilitator. Learn more and apply here.

There’s an Open Thread coming up on Feburary 1, at 12pm EST. Keep your eyes peeled for an email inviting you to the conversation.

Looking for Neil Young MP3s on my external hard drive,

Josh

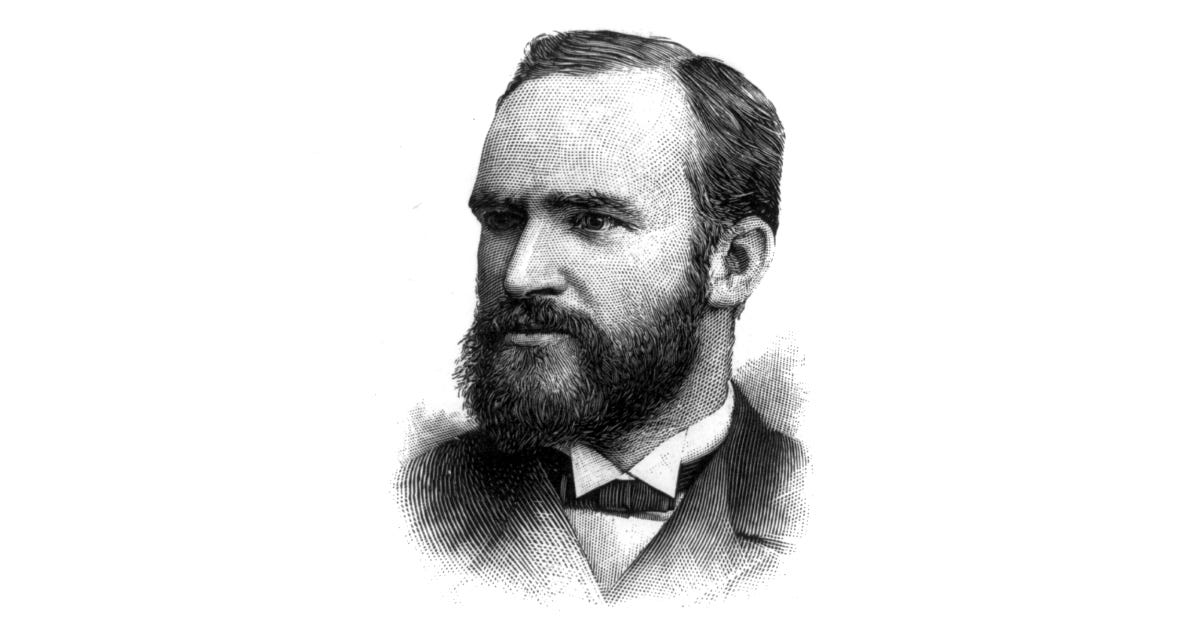

Design and illustration by Josh Kramer. Dewey photo from the Library of Congress, Benjamin Franklin painting and Carnegie photo from the Smithsonian.

New_ Public is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin, and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America.

Foreshadowing Carnegie, Franklin also understood the value of philanthropy that would grow in value and usefulness over time. His will allocated a small fortune to the cities of Philadelphia and Boston, but stipulated that they not be fully released until 200 years later, after it had compounded with interest.

There's a great deal of anxiety, nuance, and complexity in the history of the public library movement, alongside the evangelism of heroic men and women (who deserve much more than parenthetic reference), and which offers deeper lessons regarding pitfalls and perils attending the incorporation of movements into institutions. Look to the story of Chartist reading rooms in the 1840s and 50s in England, which put pressure on official culture to sanction reading access for the people; look to the story of libraries in the Jim Crow South, how they went along--and how resistance operated.

".. private, member’s only organizations.." Too many apostrophes. Adding apostrophe s usually does not make a noun plural. It actually turns into a contraction: "... member is..."