#17: Checking Out the Library’s Social Secrets

+ What would Jane Jacobs be like as a video game character?

Welcome to Civic Signals, the newsletter about the (internet) AND (public space).

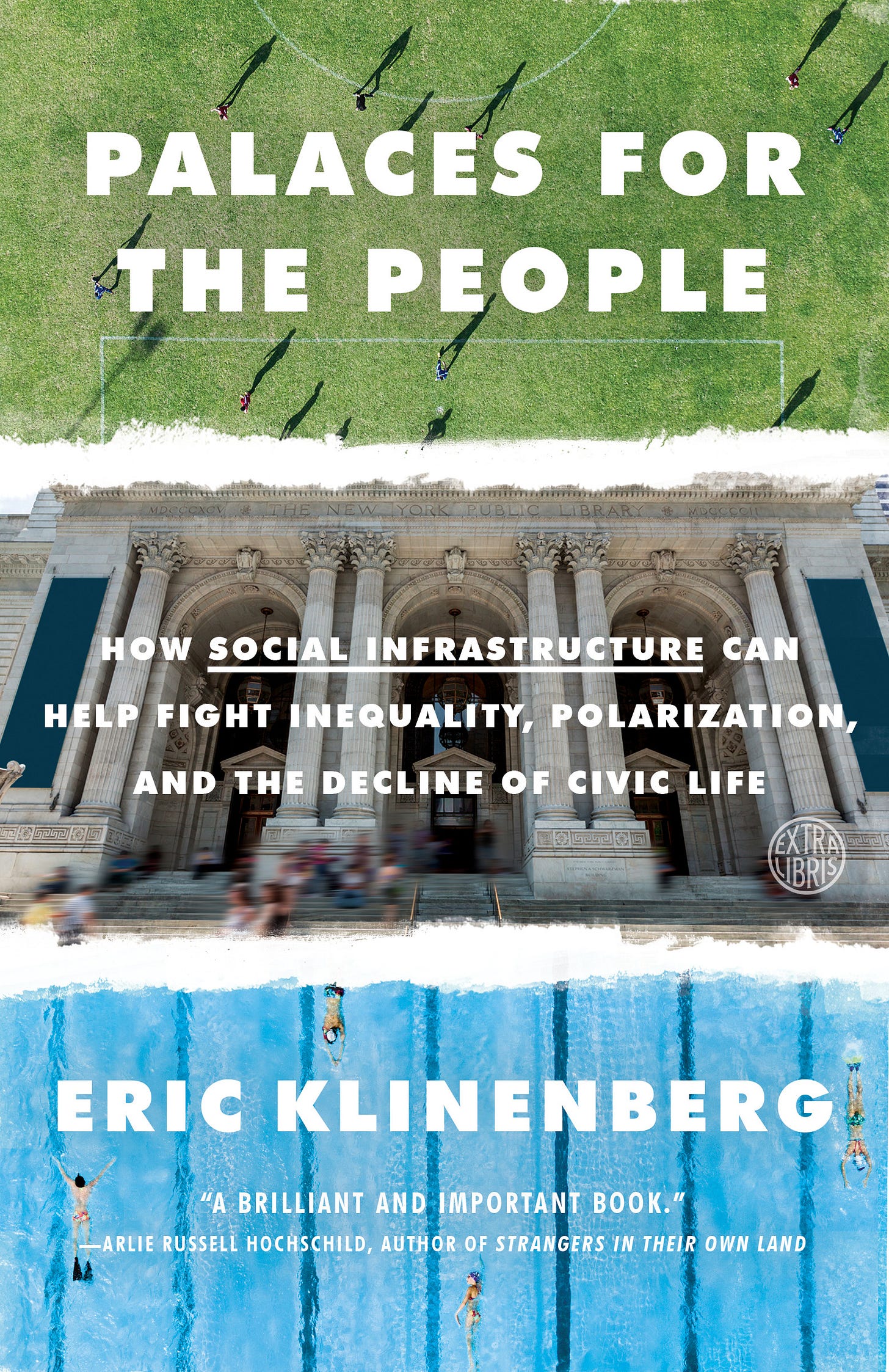

This week: A deep dive into libraries, online and off, with Palaces of the People author Eric Klinenberg. Find out what he learned from spending an entire year in libraries, and why he thinks the internet could use a lot more librarians. First, let’s get positively Aristotelian…

Keywords: Boolean

Adj. Denotes a system of symbolic logic that uses various combinations of logical operators such as "AND," "OR," and/or "NOT" to establish relationships between items.

Created by mathematician George Boole in 1847, Boolean algebra applies mathematical logic to language, setting a key foundation for the information age. Drawing from Aristotle’s logic, Boole turned categories into a way of organizing human thought through numeric representations of “true” or “false” statements. Boolean search is now the language of databases like libraries and search engines, applying limits to a query. Boole describes how language places limits on the “universe of discourse” in An Investigation of the Laws of Thought (1854).

What’s clicking

🌐 Online

How Apple will declutter its home screen - OneZero

More Americans are being harassed online because of their race, religion, or sexuality - The Verge

Social media giants support racial justice. Their products undermine it - New York Times

🏙️ Offline

Nine ideas for making public spaces more race equitable - Los Angeles Times

Design hacks will dominate the coronavirus recovery landscape - CityLab

When luxury stores decorate their riot barricades with protest art - New York Times

🔗 Linked

How Uber turned a promising bikeshare into literal garbage - Motherboard

Can a neighborhood become a network? - Curbed

Fireworks are booming in American cities. Conspiracy theories are booming on Twitter - The Atlantic

☞ This week’s Double Click

Making the rounds this week is this fun senior thesis video from Micah Epstein called Age of Automobility. Epstein, a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, created this video-game-style battle of bikes vs. cars.

We asked Epstein to tell us a little more about their inspiration for the animation. Epstein shared the video on New Urbanist Memes for Transit Oriented Teens, the urbanist Facebook group, which they credit for showing how this rackous political discourse could actually be fun and playful. Epstein writes to CS:

I chose the format (8-bit video game) because I think transportation advocacy can oftentimes be a really dry topic. I wanted to create something that made these really important topics a little more fun and accessible. I wanted to depict neoliberalism and car-based transportation as “the bad guy” (which is certainly how I see it). I thought making a quippy, underdog protagonist would help people cheer for sustainable transportation. Finally, I wanted to depict urbanist interventions (Transit-oriented development, bike lanes) as these kind of magical powers, that have a positive impact in the world.

From our Advisory Board: Danielle Allen spoke with WBUR’s On Point Radio about reimagining democracy for the 21st century

Card Infrastructure

Behind the scenes at Civic Signals, we’re currently working on a design sprint with a group of architects, designers, community organizers, educators, and librarians. This team is striving to come up with a prototype emulating the public small-group meeting—think of a story hour for kids or a seminar for entrepreneurs. Until the recent pandemic, these are the kind of gatherings that a library would host. But as these small meetings have migrated to online video conferences, the ability to create new social ties that analog meetings casually produce has been diminished. The problem is you can’t exactly put search terms on those relationships like looking for a book or website.

To get at why libraries are such great facilitators of these kinds of in-person interactions and generally improve democracy, Civic Signals spoke with our board member Eric Klinenberg, the author of Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, to get at what it is about libraries that make them such important places for meeting strangers and building community. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length with emphasis added.

SMALL: For those of us who have not yet read your book: What is "social infrastructure?"

KLINENBERG: The way I see it, social infrastructure refers to the set of physical places and organizations that shape our interactions. When we invest in social infrastructure, when we design it, when we build it, when we maintain it, we get all kinds of benefits. We are more likely to get to know the people around us, to have serendipitous encounters, to bridge divisions. But if we don't pay attention to social infrastructure, if we don't invest it, if we don't maintain it, if we don’t design it well, we're much more likely to get atomized and hunker down on our own.

Think of a playground as a piece of social infrastructure: Try to imagine how many relationships between families exist because two parents take their kids to the same playground frequently enough. Communities form because after that initial relationship is developed, people find other ways to connect. When you think about what it would mean to live in a neighborhood or town that doesn't have a playground, you can start to see what social infrastructure does and why it's so important.

SMALL: It's that serendipity of soft ties that online space tends to lack.

KLINENBERG: You can be surprised by a website or someone's tweets, but that's a very limited kind of serendipity. The kind of relationships that emerge in physical space from face-to-face interaction are more pregnant with possibility and meaning.

Let me be clear, not all serendipitous encounters are happy or healthy ones. When you have a divided society, when you have an unequal society, encounters with someone else or between groups can be fraught with danger and insecurity. There's certain kinds of social infrastructure that encourage us to interact in a more peaceful and productive way and others actually heighten our divisions and make us more kind of confrontational.

Think about what it's like to interact with someone you disagree with on Twitter versus what it is like to disagree with someone in a school or in a library or a conversation group. They're very different contexts and that really shapes who we are and how we relate to one another.

SMALL: A lot of internet culture looks to the library for its ethos with the notion that "everything should be free." Reading your book, I suspect there's another sense of what it means to be “free” in a library.

KLINENBERG: The library is the main social infrastructure that I write about in Palaces for the People. The title of the book comes from a phrase used to describe the library as a palace that is generous to everyone who enters into it.

Andrew Carnegie was kind of a jerk, he’s not my role model or hero and he was pretty comfortable with all kinds of inequality, but it's worth saying that he was a great benefactor of libraries, in the United States and around the world. He believed in this idea that the library should be a place where people could go to make more of themselves and he had this notion that the library would work best if it was open and accessible. Carnegie partnered with cities around the world and said, "Look if I build this, I put the funding into building the structure, I need you to take it over.” That deal has changed a lot of places, it's changed civic life in a lot of places.

To write the book I went to public libraries almost every day for a year—branch libraries, the little ones, not the grand ones with marble lions—and just watched what happened there. I can see why the library would be a model for people who design sites on the Internet because the library does some extraordinary things. The rooms are programmed to support certain kinds of behavior so that some rooms that are clearly for young people who are there to get to know books and build literacy or meet their neighbors, take classes. Other rooms that are there for older people to read newspapers or take knitting classes together.

Libraries are also programmed by people these magical creatures called librarians and turns out one of the things I learned spending time and physical social infrastructure is that having people there to organize and moderate and secure the peace makes a massive difference. One of the things about life online is there's not a lot of moderation most of the time. So you've got this weird situation where you've got people treating each other like bubbles on the screen not really recognizing their common humanity. That's just very different from the library, which recognizes it immediately.

SMALL: It struck me just like the example that you used in the book of people playing Wii Bowling as a throw back to Robert Putnam's Bowling Alone. I think a lot of people would assume that we don’t need a library for playing video games.

KLINENBERG: There's a scene in the book you're describing where a lot of old people at a branch library in Brooklyn come together every week to participate in a virtual bowling league. They do it together in the basement community center of the library and compete against the teams organized by other branch libraries in Brooklyn over a Wii system. It's just amazing to see all these old people who have every reason to be home and alone, feeling disconnected from technology and civic life. On its face, they come to the library to do media and technology, but it's more about their social life together. There are all kinds of ways in which libraries support activities like that.

SMALL: Is there any lesson from the library that we can translate into digital space?

KLINENBERG: The library as a built structure really dignifies people who come in to use it, there's something about walking into a library where you feel the generosity of the building and of the people that support it. The library lifts you up because when you feel dignified by a place, when you feel welcome there, when you feel like the place is going to teach you generously and recognize your humanity—that really encourages you to be the best version of yourself.

I just don't know that the Internet is built in such a way that we go into it like it honors and benefits us. In the last decade or so [the web] become more of a site for commerce and we are the product, I think we feel that. But when you're on the site where you're not necessarily the product, where the designers of the site have built it in such a way that makes you feel dignified and recognized when there's some kind of public good or social good that they're trying to produce.

Maybe where you're given the capacity to shape this way the site works, where there are people who are moderating, trying to ensure that the communication is robust and healthy and mutually respectful. Maybe an environment like that you can do something a little bit better and maybe you can start to reproduce something like what the library is.

SMALL: You wrote this book pre-COVID, but you pointed to how we spend more time socializing on the internet as evidence of how these public places have declined. What do you think it’s shown us in their absence?

KLINENBERG: It’s highlighted the lack of maintenance we've done for social media as social infrastructure. We have made social media operate as a kind of communications infrastructure, but that can't really be social infrastructure in the way the library or a park or a playground is. And I think one of the very hard things at this moment is that we've had to use them in that manner.

SMALL: Civic Signals is in the middle of a library-inspired sprint, working with architects, designers, librarians to design a digital tool or prototype for an idea that might imitate the library’s virtues online. What features of a library can you see being emulated online?

KLINENBERG: The library is organized around the principle of inclusion and access and so everyone is welcome in the library. You don't have to be a citizen. You don't have to be of any particular age, it doesn't matter how much money you have, what race you are, what gender or sex you are—you're welcome in the library, it's your place.

Access to the internet is profoundly unequal in the United States. The internet is a consumer good. You pay for it, you pay a lot for it. The first and most important thing we need to learn from libraries is to be inclusive and to create access.

Another thing we need to learn from the library is how helpful it is to respect people's privacy. We need to encourage people to roam where their minds take them, to follow their interests without worrying about having a digital record that you can't erase. A library respects people's privacy, a librarian will never ask you why you're looking for something or turn over the records of what you're taking out to the government. Online, it's very hard for citizens to control the record of their own data, their own search history. It's not private, it belongs to the companies that dominate the Internet companies that run our sites.

Finally, I would say there are enormous issues about who could replicate the work that librarians do on the Internet. What would it mean to have a moderator and community, who pays for that? We pay for librarians, they're public servants. Are we willing to make a public investment in people who would organize the Internet in some way? That could generate some concerns but also great goods, but we haven't even started conversations like that in most places.

Editor’s note: Follow along on Twitter for more on our library design sprint and stay tuned to see how some of these very principles are reflected in Civic Signals’ framework for digital public space coming later this summer!

#MakeItDigital Mailbag

We’re still taking in ideas for our #MakeItDigital callouts, where we look at online analogies to our favorite urban features. We wanted to give a quick shoutout to our first participants:

Michael Tolhurst writes to us on Twitter about the corner store. He says that the Facebook page set up to promote curbside dining in his city has become something he regularly checks to hear from people posting about their favorite restaurants while restaurants update customers on their hours of operation. Meanwhile, Maya Agapova tweets that she’s always found a community with her online fandom spaces, though no word on whether there’s one for street chess fanatics.

Keep sending us your ideas about your favorite online and offline places at civic.signals@gmail.com or @ us on Twitter with #MakeItDigital.

See you soon,

Andrew Small

Illustrations by Josh Kramer

Civic Signals is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America. Please share this newsletter with your friends!