☮️ Lessons from a radical, anti-establishment bulletin board

From the Berkeley Free Speech Movement to context collapse

This week at a glance:

🚫 Our contemporary, context-less social media is not inevitable

🏖 A sense of place helps ground a network in context

💰 Incentives and funding structures help explain context collapse

I want to start with an anecdote from the prehistory of the internet. Here’s author, educator, and artist Jenny Odell in her book How to Do Nothing (emphasis mine):

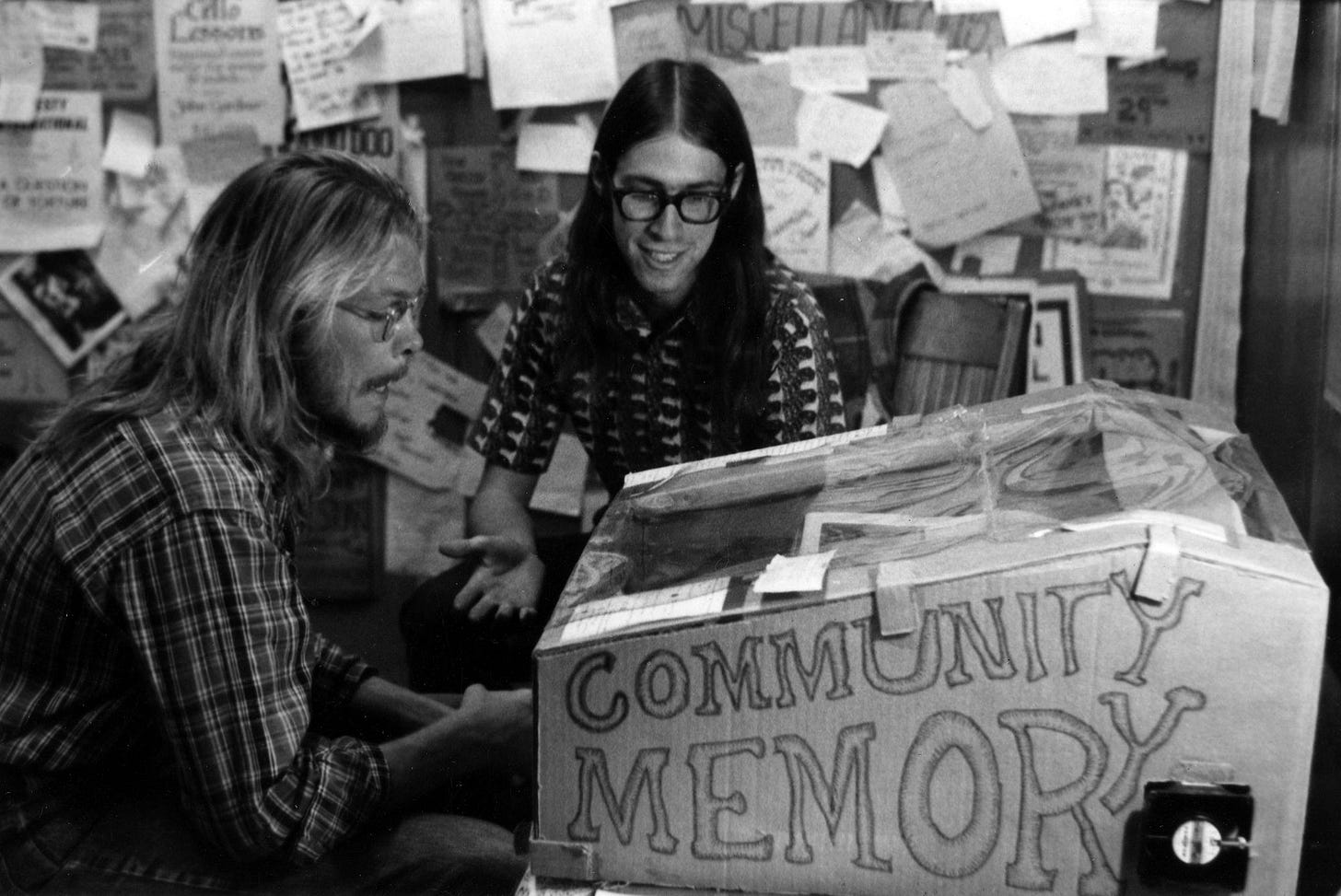

In 1972, the world’s first public bulletin board system (BBS) appeared in the form of a coin-operated kiosk at the top of the stairs to Leopold’s Records in Berkeley. It was called Community Memory, and it contained a teletype machine connected via a 110-baud modem to 24-foot-long XDS-940 time-sharing computer in San Francisco. Every day, over and over, the modem made and received calls to the San Francisco computer, ultimately printing messages for users on the teletype machine.

Whether or not you’ve ever heard of a BBS before, it might be a bit hard to understand Community Memory’s significance to our project here at New_ Public. Sure, this is one of the earliest examples of a new kind of digital communication. But without proper context, there’s a risk that you miss out completely on why it is such an important touchstone for the development of flourishing digital public spaces. Let’s go back to 1964:

🕦🕚🕥🕙🕤🕘🕣🕗🕢🕖🕡🕕🕠🕔🕟🕓🕞🕒🕝🕑🕜🕐🕧🕛🕦🕚🕥🕙

Eight years before Community Memory, “the Berkeley campus of the University of California was rocked by the Free Speech Movement,” as the school’s library website puts it. A season of sit-ins and mass arrests culminated in changes to university policy and kicked off at least a decade of vibrant counterculture.

Community Memory emerged from that thinking. It was created by Resource One, a project of several ex-students from Berkeley who sought to use computers — which few people had experience with in the early 1970s — for the anti-war and anti-establishment movements. If that sounds deeply serious, know that they also prioritized play and experimentation. Set in an abandoned candy factory, this scene of radical technologists was more Ghost Ship than Xerox PARC.

Here’s how Resource One wrote about the project: “The idea is to work with a process whereby technological tools, like computers, are used by the people themselves to shape their own lives and communities in sane and liberating ways. In this case the computer enables the creation of a communal memory bank, accessible to anyone in the community.”

Several aspects of Community Memory are worth highlighting: It was run on a donated mainframe, and posts were free to read but twenty-five cents to write. It was also facilitated in real time by an employee who would sit next to the terminal and assist users. And while posts initially followed the norms of the physical bulletin board next to the terminal, it didn’t take long for the posts to venture into poetry, ridesharing, bagel recommendations1 and politics. Because you could only read posts written on the same terminal, the content was necessarily specific to the location. Later, when there were additional, unconnected kiosks, each terminal took on its own unique character.

Each piece — the human sitting next to you, the nominal fee, the common location — contributed to a rich, contextual collective platform. As we’ll explore below, contemporary platforms often lack this, resulting in the widely discussed phenomena of context collapse.

If a concept keeps coming up, or we think it's a particularly good one that could use a little unpacking, we'll take a closer look here, in "Better Know A Concept."

Context Collapse

The background: The term “context collapse” was coined by researcher and author danah boyd, who explains its origins here, crediting Joshua Meyrowitz’s 1986 book No Sense of Place as an important influence. boyd wrote in her 2002 MIT Media Lab thesis, “Without knowing the context and history of a given [group] or individual, or the social norms of a given time period, messages can be easily misinterpreted.” For example, when you encounter a tweet, you often know who writer’s location, their professional and cultural background, what they were going through when they wrote the tweet, etc. Remember that Twitter began without the ability for users to retweet a post, amplifying it out of its original context. Over time, most of the popular platforms have become less contextual and their business models have tended to prioritize maximizing advertising revenue over all other interests, including meaningful context.

In action: There are many consequences to context collapse, as you may have observed in your own experiences on social platforms. As Odell said in a Talk at Google, because you don’t know who will be reading your posts and what type of familiarity they have with you, writing for contemporary social media means you will be “really boring and banal and uninteresting to everyone, or you're going to offend someone.” Another common result is the uncanny sensation of emotional whiplash scrolling through your feed — seeing the extremes of the human experience with no way to process what you’re seeing can leave you feeling numb and empty. Or, because you missed the origins of a controversy, particularly bad take, or inside joke, nothing you’re seeing makes sense.2

In digital public spaces: We believe that even though context collapse can be found on nearly all popular social media platforms, it is not inevitable. One example we point to is Vermont’s Front Porch Forum. Writing in The Atlantic, Anne Applebaum and Peter Pomerantsev describe it as a reliable venue for civic discussion, job hunting, and everything else. “Instead of encouraging users to interact as much and as fast as possible, Front Porch slows the conversation down: Your posts come online 24 hours after you’ve written them,” they write. “Everyone on the forum is real, and they have to sign up using real Vermont addresses. When you go on the site, you interact with your actual neighbors, not online avatars.” Notably, FPF is ad-supported, but advertising does not drive the design of the platform. They also run on donations and are set up as a benefit corporation, or “B Corp.” I discussed the platform recently on the Look Both Ways podcast:

Scott Hermes, host: Interactions on the Vermont Front Porch Forum are a lot more like Community Memory than Facebook and Twitter. Why? Because the CONTEXT of those interactions is clear and contained. Anything being submitted there isn’t written for EVERYONE that person knows. Messages aren’t aimed at gaming the algorithm and going viral. Because in addition to being part of the same physical community, the shared characteristic of people there is the fact that their attention is NOT being sold.

Josh: You understand that these are people in your community talking about things that they care about. And so if you want to, like, sell a tractor, or plan an event, this is a great way to do it. And, you know, there's a serious caveat, which is that these are small communities, and they're all pretty rural. And they're all pretty homogenous. But there is something here, you know. And there are platforms like this that currently exist, that have the kernels that we're really excited about, that we think could end up fueling the next generation of big platforms.

If you want to hear more about Community Memory, Front Porch Forum, and my attempt at a conversational explanation of New_ Public and digital public spaces, please listen to the whole episode here. (I think it came out really well! Thanks to producer Maxx Parcell for inviting me on.)

Off next week

We’ll be enjoying the holidays with family and friends, so we’ll see you back here early next year. Happy Holidays! Thanks for making our first full year of the newsletter a success and for reading each week as we continue to experiment. If you’ve enjoyed the newsletter, please consider sharing it with someone who you think would like it.

Also, starting Monday and running through the end of the year, every day on Twitter we’ll have one fun, non-article tweet, which we hope will be like opening a little present from us to you. 🎁

Hearing those sleigh bells jingling (ring tingle tingling too),

Josh

Images from the Computer History Museum, banner design by Josh Kramer.

New_ Public is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin, and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America.