🕵🏼♀️✅ Fact-checking’s future: can social media handle the truth?

Who should decide what’s true online?

We’re still seeking candidates for Head of External Engagement.

Readers: This newsletter is a little bit special, because as a companion to the essay below, we’re hosting a conversation with our community using a few prototype tools we’ve been building. Please help us learn more and refine these tools by adding your voice on the issue below.

Going back to Eisenhower, American presidents have used their farewell address to warn about threats to the nation. Last week President Biden cautioned: “Social media is giving up on fact-checking.”

Biden was referring to the announcement from Meta Founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg that the company’s social media platforms, Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, would no longer be using third-person fact-checking, and instead would be switching to a system similar to Community Notes on X (formerly Twitter).

And whatever you think about Zuckerberg, fact-checking is connected to a larger, complex problem. While many conservatives have strongly opposed Meta’s fact-checking and moderation practices, some progressives have also voiced concerns about their political speech seemingly being suppressed by Meta’s platforms.

But is it the job of social media platforms to pay for independent, neutral fact-checkers? If so, how did it become their job? Is Biden correct that they are giving it up? And if they are, how alarmed should we be? Or, is this task better-suited to the wisdom of the crowd or something else?

Below, I’ll explore the past, present, and future of fact-checking on social media. Specifically, I’ll attempt to identify who has traditionally had the responsibility for accuracy of social media content, how that is shifting across platforms, and which approaches actually seem to work best, according to research and experts. We want you to weigh in as well, and we’re excited to get your opinion.

Moderation vs Fact-checking

Let’s be as clear as possible in what we’re talking about here: “moderation” is how platforms ensure that content being posted by users follows the rules. It’s important to note that most platforms do not have a legal responsibility to remove false or even slanderous speech. Not only does Section 230 shield companies from those kinds of lawsuits, the Supreme Court has actually gone further, ruling that moderation itself is constitutionally-protected speech. But there are, of course, other incentives for moderation, including advertisers, bad press, angry politicians, civic obligation, etc.

Platforms typically moderate in a few different ways: posts, comments, or account info (like a bio) can be flagged for review, or identified by automatic systems, and then if those items are found to violate a policy, they might be removed or result in action like a suspension or ban.

“Fact-checking” is often part of moderation, but it’s very specific, and usually refers to verified, non-partisan professionals outside of the platform deciding what’s true. Once they have made that determination, the platform takes moderation actions based on their judgement.

In fact, most moderation doesn’t involve the active participation of outside fact-checkers. Fact-checking, even the “industry-leading fact-checking program” Zuckerberg described to Congress in 2021, is relatively slow and labor-intensive, with fewer than ten items on Facebook being fact-checked on average each day.

Moderating typically looks more like setting a red line in platform guidelines (based on a government agency, a history book, or something else definitive) and saying that everything that crosses it will be reviewed. Examples include Reddit during COVID, Discord after the pandemic, and Snapchat’s rules about denying events. If a comment clearly goes against your company rule about denying the Holocaust, it’s far easier for a moderator to take action, without an expert fact-checker actively involved at all (except in some cases by helping determine where that line is beforehand). Content moderators don’t have to assess whether something is a lie, just whether it’s breaking a rule.

Contrast that with Meta’s automated systems and tens of thousands of content moderators worldwide, who review millions of items a day. While Meta is also making changes to their non-fact-checking moderation practices, and that is really important, let’s keep focused on fact-checking.

That isn’t to say that the distinction is completely straightforward: LinkedIn’s policies say that they’ll remove “specific claims, presented as fact, that are demonstrably false or substantially misleading and likely to cause harm.” But they say nothing about how they determine that, and if they use any fact-checkers to do it.

Where social media fact-checking came from

For most of the history of social media, moderation as described above — setting a line and holding that line — was enough for most platforms.

But, as you may remember, Facebook took quite a lot of heat after the 2016 election. After widespread Russian interference, the platform leaned hard into external, third-party fact-checking. In checking in with researchers, most of them now regard 2016 as when misinformation began to be taken seriously.

“We do not want to be arbiters of truth ourselves, but instead rely on our community and trusted third parties,” Zuckerberg wrote in November that year. Facebook set about partnering with the International Fact-Checking Network, creating neutrality standards and verification requirements, including independent assessment and peer review.

Zuckerberg later explained to Congress how the program worked:

If content is rated false by one of these third-party fact-checkers, we put a warning label on it. And based on one fact-check, we’re able to kick off similarity detection methods that identify duplicates of debunked stories. When content is rated false, we significantly reduce its distribution; on average, this cuts future views by more than 80 percent. If people do try to share the content, we notify them of additional reporting, and we also notify people if content they have shared in the past is later rated false by a fact-checker.

In the years since, other platforms have adopted third-party fact-checking as well, including TikTok, which has a “Global Fact-checking Program” … for now. (As of this writing, TikTok’s future operating in the US seems tenuous at best.)

Meanwhile, even before the 2020 election, Twitter used fact-checking to help identify COVID misinformation and apply warning labels, including to tweets from President Trump. They were also experimenting with a whole new system that would be released as Birdwatch, later rebranded as Community Notes and used widely under Elon Musk as CEO.

This novel approach lets users write labels for posts, which are then sorted and picked by an open-source algorithm that prioritizes bridging different perspectives and opinions. This crowd-sourcing of helpful context has provided a new model for Big Tech. Not only has Meta announced its intention to adopt something similar, YouTube has also implemented a pilot for user-generated notes picked by a bridging algorithm.

What actually works

So, after eight years of fact-checking on Facebook, and several years of Community Notes on X, what do we know about which approaches work best?

There is also a lot of research that both third-party fact-checking and Community Notes can be really effective at reducing misperceptions. But — and this is a significant caveat — neither works well as a complete solution for lies on social media.

When Twitter was working on Birdwatch, they claimed it would “not replace other labels and fact checks Twitter currently uses”. But as I’ve written about before, Musk scaled back Twitter’s Trust and Safety team significantly and positioned Community Notes as the replacement. As Yoel Roth, Twitter's former head of Trust and Safety, told WIRED, “The intention of Birdwatch was always to be a complement to, rather than a replacement for, Twitter's other misinformation methods.”

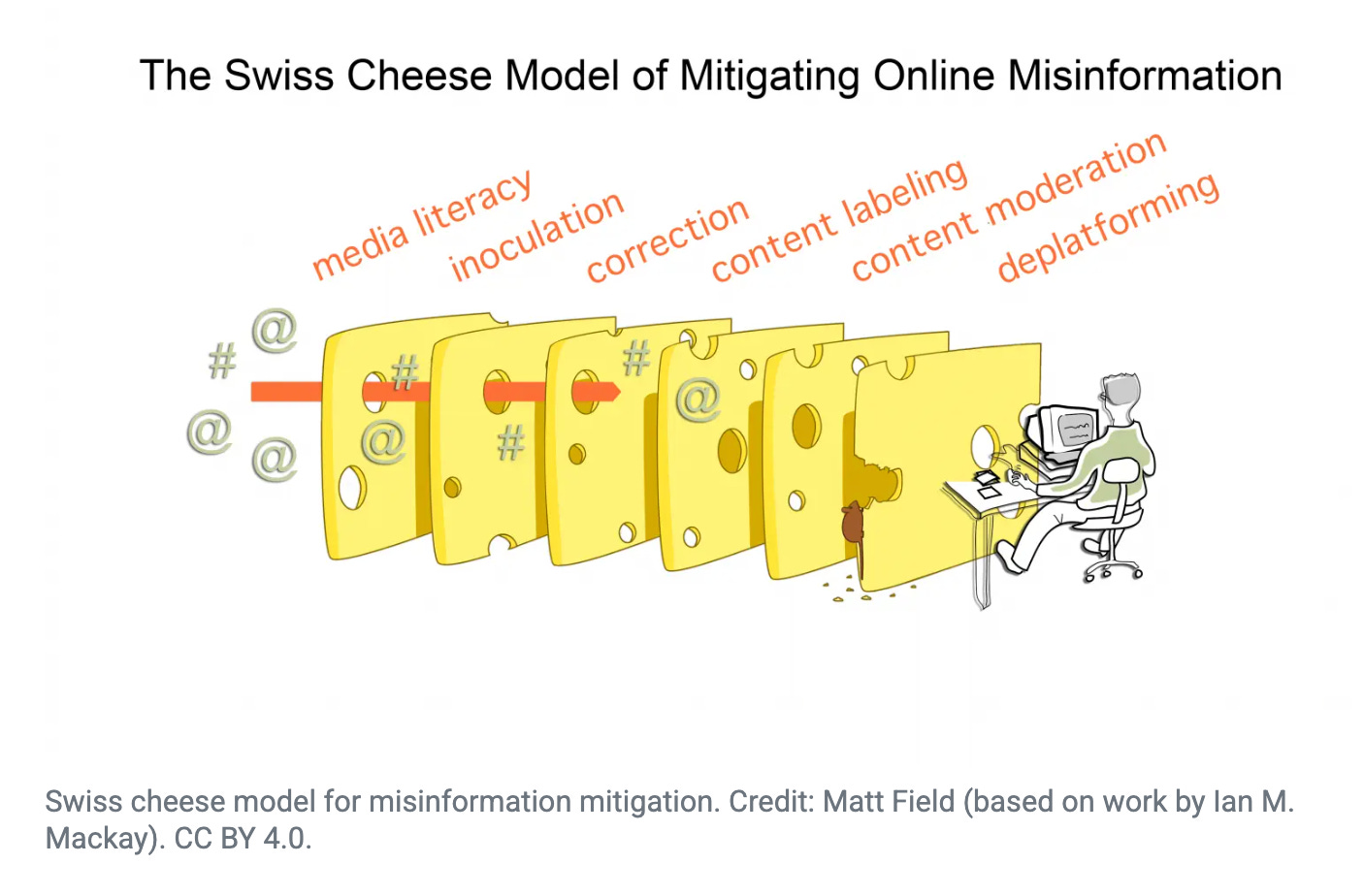

In fact, research on various attempts to mitigate COVID misinformation found that a layered, “Swiss cheese” approach might work best, where some efforts work well sometimes, but collectively the system catches most falsehoods.

In terms of fact-checking’s effectiveness on Facebook, researchers Jonathan Stray and Eve Sneider say it simply “never achieved scale.” As discussed above, there just weren’t enough items being fact-checked to have any real impact on a platform with billions of users.

But with false information, it can be hard to know whether it’s better to label and correct it (and risk amplifying it further) or just remove it. But there is also some question of whether fact-checked posts or Community Notes actually reach as many people as they should. A report from the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that even though there were many accurate Community Notes labels proposed for false tweets about the 2020 election, they were often not actually applied or shown to most users.

Timing is also a factor. Bridging between different notes or getting an outside fact-checker to weigh-in takes time. If the label comes too late and most of the re-posts have already happened, that’s not a very effective intervention. New research suggests that AI-boosted “Supernotes” could be added as soon as two hours after posting (as opposed to an average of 15 hours for normal Community Notes on X). But even if Meta implements the very best version of Community Notes, no single approach will be perfect.

Other fact-checking considerations

Fact-checking isn’t deployed uniformly by every platform. Some, like Snapchat, use it primarily for advertising, having fact-checkers verify “all political and advocacy ads.”

In fact, some social media platforms more organized around smaller groups, like Discord and Reddit, empower their community stewards to take on fact-checking if they want to. Moderators can build and install bots that use an API from Google’s Fact Check Explorer, bringing vetted fact-checking in from outside sources.

Even more could be possible in spaces that are actually decentralized. On Bluesky, users can not only choose their own feeds and filter content however they like, they can also choose their framework for moderation — above a floor set by Bluesky.

Last week, New_ Public’s Co-Directors, Eli Pariser and Deepti Doshi, joined the Free Our Feeds project as advisory Custodians, and explained their thinking in MIT Tech Review. Here’s what they had to say about choice on Bluesky:

At the core of Bluesky’s philosophy is the idea that instead of being centralized in the hands of one person or institution, social media governance should obey the principle of subsidiarity. The Nobel Prize–winning economist Elinor Ostrom found, through studying grassroots solutions to local environmental problems around the world, that some problems are best solved locally, while others are best solved at a higher level.

In terms of content moderation, posts related to child sexual abuse or terrorism are best handled by professionals trained to help keep millions or billions safe. But a lot of decisions about speech can be solved in each community, or even user by user as people assemble Bluesky block lists.

However, Ostrom herself often warned about panaceas. Researcher and author Renée DiResta has warned that “federation … makes it significantly harder to combat systemic harms or coordinate responses to threats like disinformation, harassment or exploitation.” It’s also possible that being able to choose your preferred moderation scheme might only make things worse: If given the choice, people might choose moderation consistent with their beliefs that amplifies misinformation they agree with. To some, this might be an acceptable price for freer speech online.

Confronting lies and manipulation online was never going to be easy. For a variety of reasons, the status quo now appears to be shifting. What do you think? Should social media platforms be responsible for fact-checking? Tell us here.

Not minding the cold weather all that much,

–Josh

Just a note: please comment through the link instead of here this week. Thanks!

lol Orwellian