The last time I used the BabyConnect app, it was to record nursing my son at bedtime. It was April, the day after my birthday, when X was 14 months old. I had gotten my second Covid vaccine shot that day, and I was ready to emerge (I thought) from the claustrophobic huddle of life with a pandemic baby. The feed lasted 23 minutes and at the end of it I hit pause on the timer, rather than stop. The clock kept running in the background, dutifully keeping track, until the next time I opened the app, which, as it turned out, was 7,148 hours and 35 minutes later. Perhaps it seems odd that I didn’t close it after that last feed with a sense of finality. But that’s how change happens with children: you don’t notice you’re done, or they’re done, and you certainly don’t get to say goodbye. Not to the binky with the fluffy white bunny rabbit attached, gripped, dropped, and washed so often it turned gray like roadkill, and not to the months when it dangled out of his mouth morning and night until one day, he just stopped needing it. The binky floated off on its canoe to who knows where, and we never noticed it go.

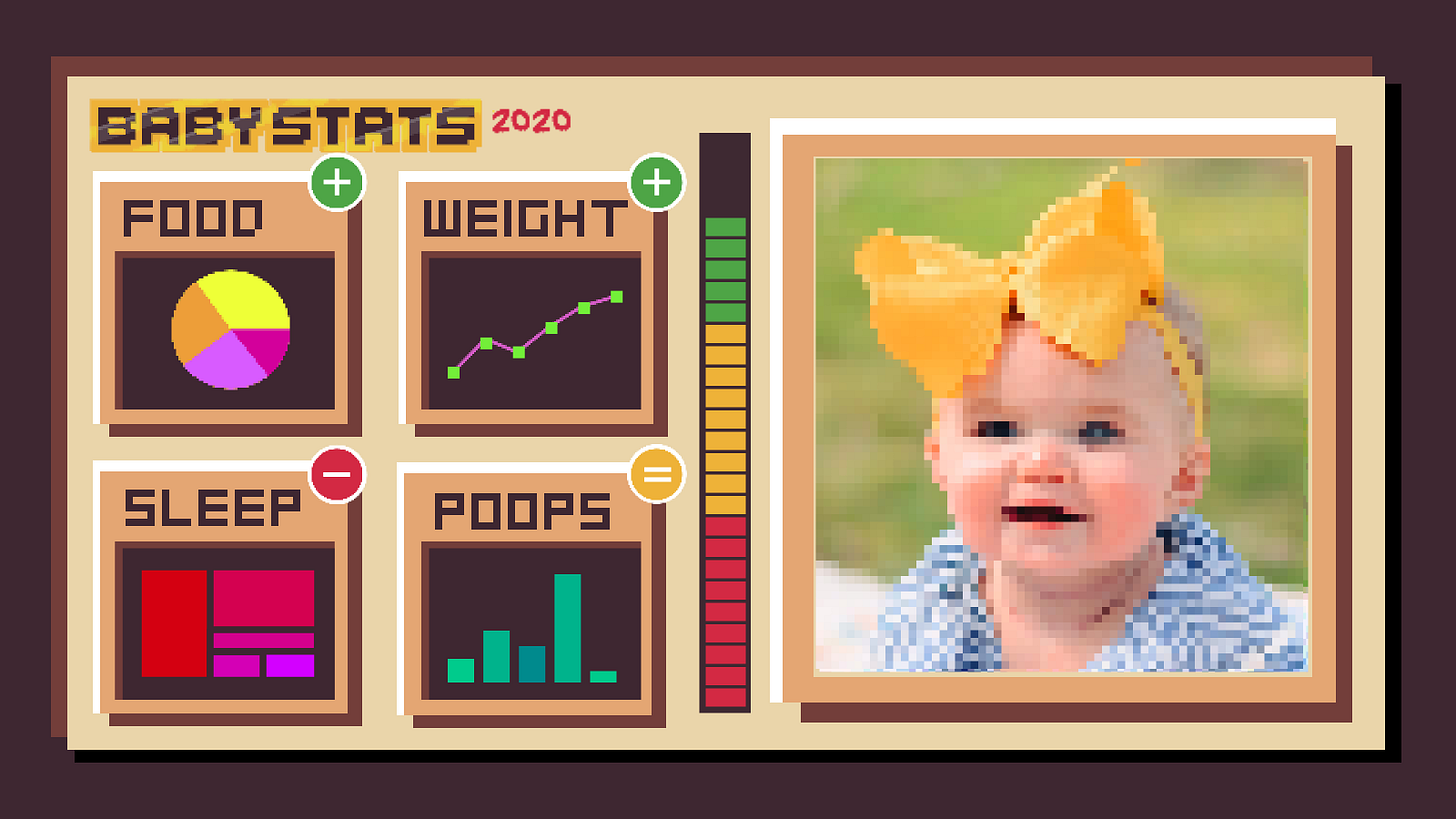

BabyConnect is a timer and tracker app that exists to mark the details of a baby’s development, to reassure new parents that time is passing and progress is being made. It was recommended to us, in no uncertain terms, by other parents we trusted, so we duly downloaded it. With its grid of gentle, pastel-colored circles and white icons, it’s simple to set up and use through the fog of anxiety exhaustion. The most important trackers are at the top, for sleep, diapers, and feeding—breast, bottle, or solid—but you can also record your baby’s mood, activity, medicines, and milestones. If you’d like, you can go even deeper: the app allows you to share information with your pediatrician, upload photos, keep a diary, make shopping lists, and call your partner. We stuck mainly to the first row of the data grid, and the only photo we uploaded was the header image, taken when X was a few hours old, tiny and sleeping and hooked up to monitors. Every time I opened the app, multiple times each day and night, there he was in his own little circle: a peaceful, fragile little stranger.

It turns out that five dollars is a very small price to pay for the illusion of control: a vital, sustaining illusion in the first weeks of parenthood. Tracking his feeds, sleeps, and diaper changes was a way of marking our progress, trusting that the amassing of experience was progress, that we knew more after ten, 45, 600 naps than we did before. More about ourselves, more about this strange new reality, more about this new person we’d brought into the world without consulting anyone. In the kinder, gentler schools of parenting advice, there is a tendency to reassure you that “you know your baby best.” But did we? In those weeks before smiles, before even eye contact, he felt as mysterious in my arms as he had in my belly. If he was known anywhere, it seemed, it was in the charts and graphs of BabyConnect. The data, at least, had our backs. For the rest of it, we were on our own.

X arrived three and half weeks early, at the end of February 2020, when visitors tramped into my shared postpartum room in regular clothes—no masks, no gloves. My mother and stepfather flew over from London for a three-day visit to meet the newborn, and we planned for when they’d come back later in the spring. The day after they left, the flights were grounded. We live in Astoria, Queens, around the corner from a major hospital, and by the time we reached my baby’s original due date, New York was a pandemic epicenter. Through the rest of March, April, and May I sat up at night in an armchair by the window feeding the baby while red lights slid across the glass and sirens rose, wailed, died, and rose again, relentlessly.

After those first social days we were alone: even our closest friends, neighbors who live upstairs and whom we’d planned to count on for babysitting, were shut away, sharing cocktails over Zoom instead of in our living room. We knew it was evening by the seven o’clock claps and hollers for the essential workers. Our friends who lived alone went months without a human touch, while I had never felt so touched—clung to, bitten, cuddled, pummeled, puked on, and worse—in my life. The worst of it was that we couldn’t share, couldn’t say Here, hold this baby. There was nobody but us to take his weight.

I’ve never been more reliant on my phone than during those months, watching social media feeds like a world through glass, then toggling between BabyConnect and a library e-book app when Twitter got too much. I manipulated the phone one-handed while I settled in to feed, trusting the minutes ticking by to translate into calories and ounces that would flesh out X’s skinny chicken legs enough to eventually fill out a newborn onesie. At first, I also hooked myself up to a breast pump, which at least proved that I was producing milk, but with nowhere to go and no prospect of separation, I gave up. I transferred my faith to the timer in the app.

In ordinary times, BabyConnect might be revealing about the division of domestic labor, since it labels who entered the information. But in our abnormal state of isolated togetherness, both working and parenting from home, my husband and I shared everything. Did you start the timer? I’d whisper-call from the other room, when we were sure the baby had gone down for a nap. My husband would change a diaper and I’d leap into action as some kind of bizarre scatological stenographer, to record the result. The app gave us a wealth of options: buttons for poopy, wet, or dry, and yes/no options for leaks, diaper cream, and “open-air accidents”—which, with baby boys, are more like gleeful target practice. Poop can be further classified by size, consistency, color. Was it more “soft” or “claylike”? “Runny” or “watery”? “Hard,” or “little balls”? A shade of brown or mustard, or alarming red, white, black? We drew the line at uploading photos, but used the comment field to vent our feelings: “Good god so much poop.” “Five-wipe tsunami.” “La Brea tar pits.” Once, simply, “DUDE.”

This is the daily reality of early parenthood, universal and utterly particular: brain fog and poop jokes. In this way, BabyConnect resembled a much older form of recording, the notebooks mothers have kept for generations, like the ones my mother found and read to me over the phone, a patchy record of my older brother’s first months (these systems usually drop off with subsequent children.) I didn’t keep a notebook consistently, feeling both the practical limitations of finding a pen and paper and a light, but more heavily the pressure to make the writing good. I couldn’t even fill out the pre-printed pages of a perky “new mum’s diary” I received as a gift; the experience was too much, overwhelming the checklists and pages set aside for those elusive milestones. It should be poetry, this experience, this overwhelming, endless, fleeting life, and I didn’t have it in me. And it was also too sad, a reminder of the strangeness of our particular experience: our park outings masked and distanced, no meeting of grandparents, babysitters, other babies. But the app didn’t ask for poetry, nor impose a picture of normal babyhood we couldn’t match. It was experience stripped of feeling, stripped of the specificity of 2020. Just an endless scroll of lovely, timeless, ultimately meaningless data.

The app would turn the data into bar charts and timelines, which we’d study to see if there was a pattern emerging. (There wasn’t.) Even at the time, I suspected that the data was a hedge against the powerlessness of simply waiting for him to grow older, to become physically able to sleep through the night. Recording it, parsing it for patterns and messages helped us feel that we were doing something in that waiting period, while we lay awake listening to coughs and coos and whimpers from the crib across the room, tensing for the escalation into screams.

When I look back on the data now, I can see growth happening inexorably, sleep stretching out, all the changes that are part of the incredible pace of growth and development in a baby: the doubling in weight, the learning, the kicking-in of new bodily functions and the abandonment of old needs. But I can’t see the story. The app offers a few pre-set menu options for obvious milestones, like “Born,” and let us add our own: “first bath without screaming!” But most of the time you don’t know what’s a milestone, what matters—like the first time he slept nine hours, and it felt like a window opening. The app gives no interpretation of the data, no analysis that will spit out a grade, much to the chagrin of mothers like me, who were dutiful straight-A students. I could tell the app that my baby’s nap lasted 13 minutes, or three hours, and record two hours of wakefulness at 4 a.m., but it wouldn’t tell me what to do about it.

In a recent WIRED article, the disinformation researcher Nina Jancowicz offered a damning assessment of popular pregnancy apps as “a fantasy-land-cum-horror-show, providing little realistic information about the journey to parenthood.” Although leading apps like What to Expect and BabyCenter have discernibly worked to counter the woo-woo—being forthright that childhood vaccines are essential and touting the medical credentials of the authors and reviewers of their articles—they are still, Jancowicz argues, in the business of building their subscriber base and mining user data for the benefit of advertisers and corporate partners. But BabyConnect didn’t look at our nights of broken sleep and suggest we spring for a Snoo; nor did it bombard me with the hotly contested pros and cons of breastfeeding. That reticence makes it rare, perhaps uniquely trustworthy, in the suite of pregnancy and new-baby apps. In our pandemic isolation, it was reassuring simply to feel we had another set of eyes on us, and on the baby. Not a judge, but a witness.

As much as we trusted BabyConnect, I see that we cheated on it, leaving no visible record of the worst disaster of our first year. At the beginning of December 2020, my husband tripped over the outstretched leg of the high chair, holding the baby. A day or so later, we discovered that X had broken his leg in the fall. The unfurling nightmare that followed—of hospitals mid-Covid surge, full-body X-rays, talks with surgeons and social workers, and getting the leg of a baby just starting to crawl immobilized in plaster—is nowhere to be seen in the app. I fed X in curtained cubicles and recorded it, but I didn’t say where I was. There are no gaps in the scroll of data: as mundane and unrevealing as ever. It was a way of reassuring myself that he was still a healthy baby, sleeping, pooping, feeding on schedule, despite the fracture. He would never remember it, the doctors reassured us, and we would never forget it. We made it to London for his first Christmas, and within weeks, he recovered completely.

In that experience, we turned to the community we had—our friends and family—and realized how much they were with us, even if we couldn’t see them in person. My friends told me stories of accidents with their kids that they would never otherwise have shared. In the new year, we put X in daycare for the first time, and he spent time with other babies. Immediately, he went down with a cold that he’s pretty much had ever since. But we found a real community, and we relied less and less on the app. We could see how much he was eating, at the table with us, and it didn’t matter so much how long his naps were once he reliably slept at night. We trusted the data for a little over a year. Seven thousand or so hours later, we’ve started to trust ourselves.

Joanna Scutts is a historian and literary critic based in New York. Her writing has appeared in venues including The New York Times, The Guardian, Slate, and the Paris Review. She is the author of The Extra Woman and the forthcoming Hotbed: Bohemian New York and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism (Seal Press/Hachette).

Illustration by Josh Kramer.

Photo by Christian Bowen, via Unsplash.