🏞️ Revisiting the public commons.

What can a medieval concept teach us about our public digital town squares

The collision of Elon Musk's takeover of Twitter with the November elections brings a renewed sense of urgency to how we think about our shared digital public spaces.

In his op-ed in this week’s Wired, New_ Public Co-director Eli Pariser pointed out that it’s time to choose a different path:

“It’s time to stop relying on a few billionaires or VCs to make key decisions for billions of people around the world. It’s time to invest in public digital spaces that actually serve the public and prioritize healthy relationships, stable communities and, well, people.

Let’s take a breath to ground ourselves, shall we? Why is there so much pressure and scrutiny on Twitter as a digital public space?

To find that out, we need to re-examine the origins, trajectory, and concept of The Commons and the Public Square and how places like libraries, parks, and cities come together to inform our shared commons, and how digital platforms create our public commons of today.

The origins and often misunderstood commons as place

When we use terms like “town square,” “public square,” or “commons” to talk about something like Twitter, do we have an equal understanding of these terms? Or are we perhaps taking its meaning for granted? Here’s a bit of a primer revisiting some assumptions we all make as we look back to build forward.

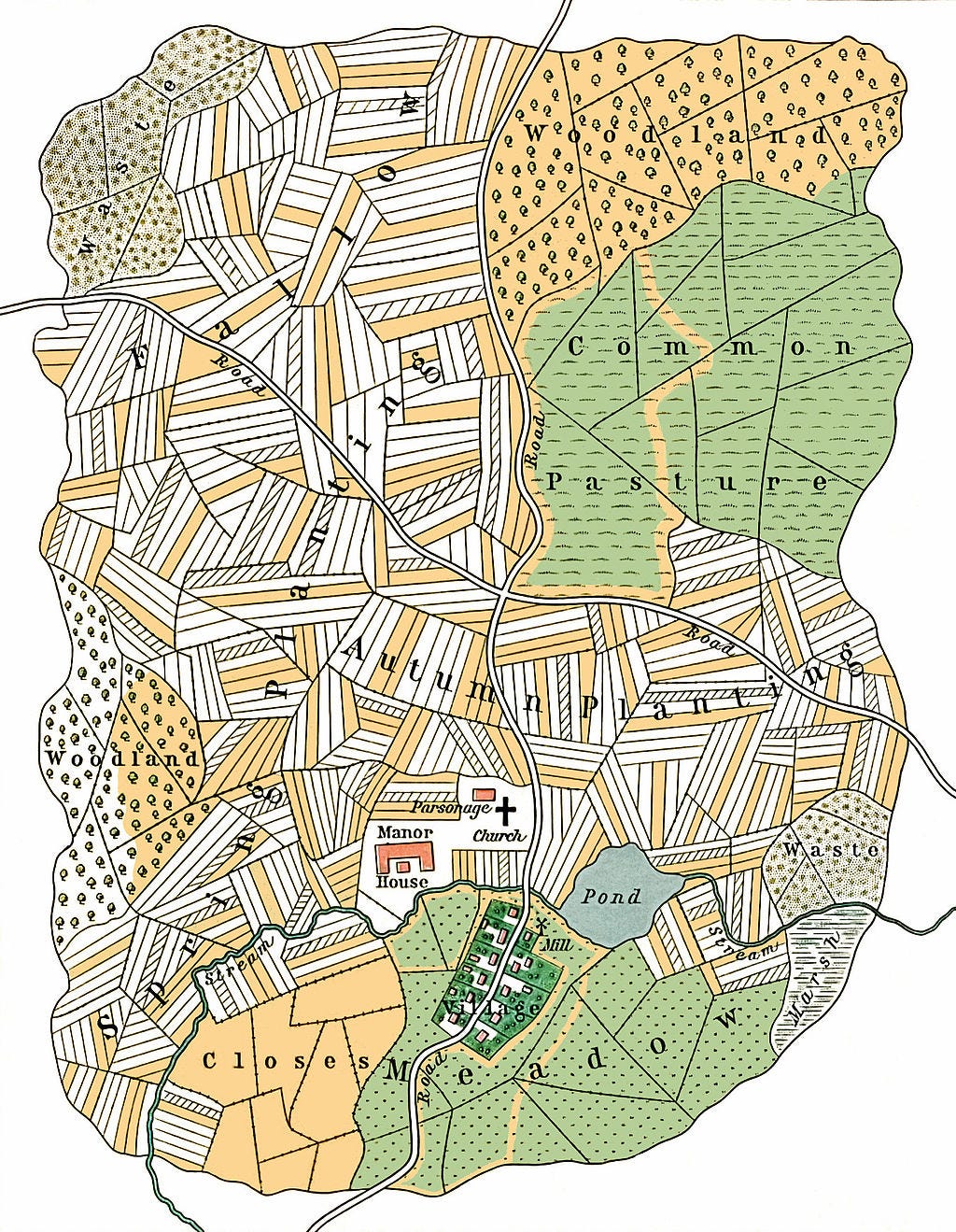

Let’s start with the origin of the term “commons.” In its simplest definition, it refers to the uncultivated land an English Lord’s manor set aside for use by his tenants. Over time it expanded to refer to the way communities managed land held ‘in common’ in medieval Europe.

Our modern-day assumptions about the commons as a free for all where citizens can do as they please is due in part to a now-famous 1968 essay by ecologist Garrett Hardin in the journal of Science entitled, ‘The tragedy of the commons.

Hardin believed the only way to avoid this chaos was via private property rights and government regulation. He wrote,

“Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep… the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy.”

However, as Eula Biss pointed out in a recent New Yorker article, The theft of the commons, “what Hardin considers the ‘inherent logic of the commons’ is actually the logic of capitalism, the dominant logic of our time. That logic dictates expansion, no matter the consequences, and it has brought our world, as Hardin warned it would, near ruin.”

But Hardin missed an important nuance. The tragedy of the commons is not an inevitability. The commons, in reality, was never a free-for-all.

Hardin ignored the communal governance and caretaking that went into the managing of the commons. Along with shared land, the community developed a clear set of rules about how the land was to be used.

Enter the digital commons - from utopia to tower of babel

Viewed as an extension of media and marketing, early websites were one-directional publishing engines, supported mainly through advertising and based on the private business model of print media.

By the mid-2000s, Web 2.0 promised an equal voice in the digital town square. We were free to post and comment and share. Participation was its own nirvana.

It worked. Well, sort of.

These digital town squares were mere villages; we were chatting amongst ourselves with an unwritten sense of the boundaries and rules and with the space and time to get to know one another.

It wasn’t all bliss. We had our flame wars. We worked them out in public. The town square was small, and as a result, the ramifications were [mostly] limited to bruised egos and bragging rights.

More and more participatory platforms were born, each with its own purpose, goal, and objectives. More and more people joined the town square. And more opportunities to share a sort of untethered digital commons were created.

Very few large sites had rules for participation. Two notable exceptions include Mechanical Turk, an early crowdworkers site owned by Amazon, where workers and requesters collaboratively determined wages, and Wikipedia, which set early policies and guidelines. There have been challenges in both these shared spaces, but there is also an acknowledgment of a co-managing of sorts aligned with the open-software movement.

Unlike the medieval physical commons, there were very few examples of shared governance or digital stewardship for sites in the Web 2.0 era. The majority of platforms were privately owned and did not design their town squares with an understanding of their greater impact or consider the broader communal implications of their participatory designs. The term social media gives us the first clue that they were not built to function as communal town squares but as inherent extensions of their publishing roots. They were designed from the top down to scale at all costs. They simply tacked on any sort of governance after the fact.

Content moderation and community management are designed to mitigate problems vs. embedding the structure of a shared digital commons by design. Mike Masnick’s recent piece, “Hey Elon: Let Me Help You Speed Run The Content Moderation Learning Curve,” is a wise and humorous take on the downward spiral of content moderation and the futility of this approach.

There is no commons without commoning

Ecologists have increasingly turned to the concepts of the commons as a guide for managing our shared resources; there is a renewed energy in commons-based society practices, examining what we own together and how we cooperate in cities across the globe.

Nathan Matias pointed out in a 2015 article entitled, The tragedy of the digital commons, that ‘advocates for fairer, safer online spaces are turning to the conservation movement for inspiration’ asking,

“If code is law online and platform designers are its legislators, who identifies the problems and sets the goals for those laws? “

Many advocates (including the New_ Public team) are inspired by Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom who spent her career documenting communities around the world and their successful management of common resources. Her work debunked the tragedy of the commons, highlighting that “what we have ignored is what citizens can do and the importance of real involvement of the people.”

Ostrom’s observations of both the success and failures of managing the commons are elegantly outlined in her eight principles for managing the commons, and they offer us a potential guide for a more equitable digital commons. Getting members of the community to write their own rules and graduated sanctions for rule violators are just two rules that could have a profound impact on our digital commons if implemented properly. What would be the result if, instead of banning bad actors from a site, which results in public shunning and backlash behavior, we designed a more nuanced approach?

Recent advocates of the reexamination of the commons, such as Jay Walljasper, former editor of the Utne Reader, look to the “commons as a new story for our future”; his book All That We Share is a field guide for the commons, packed with essays arguing for a new way of living in which the ‘we,’ matters as much as the ‘me.’

Perhaps, David Bollier, a leading theorist on the commons, sums it up best when he says, “there is no commons without commoning.”

So, although the medieval physical commons may be disappearing, the often overlooked rules that govern the commons and how we think about our digital town square can offer us a way forward. But Ostrom is careful to point out - there is no one size fits all solution. “Rules cannot last, as society, business, and technology change. Consequently, successful commons governance requires that rules evolve." It’s time to recognize that our digital commons and public squares are both place and practice, requiring design, active stewardship, and collaboration.

Multitudes of publics, designed for all

From the start, the digital town square contained multitudes. It was both a noun and a verb.

As Mastodon, Planetary, DAO’s and other server-based federalized platforms and spaces gain traction, will they be able to govern and nurture their town squares? How will they wrestle with these same issues? Are they designing for a different type of commons and participation?

At first blush, Mastodon looks and functions like a Twitter clone; how will each server deal with their trolls and bad behavior? How will we support those who step up to do the often unseen, heavy lifting of managing their servers?

In 2015, Stuart Geiger, a professor and proponent of designers and social scientists to embrace their role as the web's “civil servants,” presciently pointed out,

“If Twitter or Mechanical Turk or Wikipedia die in 10 years and something new replaces all of them, we're still going to have these issues, and the people who are tackling those issues will still care about them.”

Even back in the earliest days of the Web, we never had a singular public or commons. This fallacy of the public may function locally in a pre-industrial, pre-internet age, but as we have seen, it’s not holding up so well in our current era.

There is no singular digital town square. We live in an era of multiple public squares and multiple commons.

As New_ Public’s Signals research and our shared experiences online have shown us — our many commons and digital public squares require new design structures, a new pattern language, and most importantly, people who care for them and each other. I have faith in our ability to build up our communing digital muscles.

🍁 Off to crunch the fall leaves,

Community Corkboard

🗳️🇺🇸 Links to help get you primed for the November 8th elections.

Brennan Center for Justice, “‘News Deserts’ Could Impact Midterm Elections” A lot of voters are getting their news online rather than in their local newspapers, and it’s creating a challenging void in coverage and information. Food deserts, meet news deserts. 🌵

Coforma, on LinkedIn “Future-Proofing the AccessibleVoting.net Site for Voters” All citizens should have the right to vote, regardless of disability status. Coforma is a design-forward civic tech company that is making voting more accessible this year through their work on AccessibleVoting.net.

The AIGA “Get Out the Vote” Poster Gallery Looking for a different GOTV vibe to hang in your window or your lawn, or share on your socials? Check out the hundreds of poster submissions for this year’s AIGA initiative, Design for Democracy.

IDEO: LA County Registrar/Recorder’s Office, “Making Voting Easier”

Voting centers and polling places are one of the few remaining civic institutions where people from different walks of life intersect in person, in real-time. Here’s how IDEO worked with LA County to reimagine the public voting experience.

Apply to the 2023 Reboot Student Fellowship Reboot HQ is a good friend of ours, and their fellowship program is back for another year! Explore tech, humanity, and power through a guided book club, writing workshop, and community mentorship. Deadline is Friday, November 18, at 11:59 pm PT

The Community Corkboard is our place to help build awareness about all the exciting goings-on in the healthy digital spaces community. Do you have an upcoming event or happening you would like us to list on the Corkboard?

New_ Public is bringing together community experts, technologists, designers, futurists, and civic entrepreneurs to build digital public spaces for everyone.

great work, thank you! gonna pass to my students.

Thanks for this. I just wrote something similar in my newsletter -- albeit a bit more pessimistic. I think your point about multiple commons and public spaces is spot on!