🎙️🌍 How we're building with international public broadcasters

A deep dive into product design for public conversation

Last month we shared a first look into the Public Spaces Incubator, an international consortium of public broadcasters that aims to remake and revitalize public conversation on the internet. In this edition, we will dive into the details of what we are building and testing alongside our public media collaborators, and the product design principles that we have developed along the way.

As New_ Public Co-Director Eli Pariser noted in his recent presentation at re:publica 2024, public discourse on the internet is difficult and has never been more fragile, especially given the increasingly toxic and fragmented digital environments created by for-profit social media platforms and the erosion of trust in the news and institutions. People are increasingly fleeing to siloed, private group chats to talk to each other, leaving large absences in the digital public sphere.

But a healthy public sphere is essential to functioning democratic societies. It is a way for individuals and groups to interact with a variety of peoples, lived experiences, and ideas outside of our respective bubbles. It provides an opportunity to reason about, feel out, and make sense of the world together. We believe that public media organizations are uniquely positioned to play the role of host, moderator, and platform for such large public conversations — especially so as independent, publicly-funded institutions attuned to and driven by public interest, rather than profit and growth at all costs.

To design better public conversations online, we needed to move rapidly from this larger vision into the real context of people’s daily lives. How and why do individuals across different cultural contexts participate in public conversation? What are the obstacles that prevent them from engaging in public conversation online?

We spoke to over 200 people in our research across the four countries where our collaborators CBC/Radio-Canada (Canada), ZDF (Germany), RTBF (Belgium), and SRG SSR (Switzerland) are based — across age groups, languages, geographies, digital literacies, and relationships with public broadcasting and civic participation — and we prototyped over a hundred concepts. Through these encounters and iterations, we developed three key principles that continue to guide us through the implementation, testing, and evaluation of our interventions. We are excited to share these principles here, in hopes that they might be useful to other designers and technologists working to improve public discourse on the internet.

Design for “crowding in” over “crowding out”

Many people we interviewed over the past year of design and development wanted to broaden their understanding of important topics being debated across society — they wanted to draw connections between these issues and how they impact their specific communities, and share what they know. But when we asked them what prevented them from doing this online, participants cited fears including harassment, trolls, hate speech, misinformation, and extremism. Both anecdotally and in our research, we have found that a few bad actors or a small minority of loud, combative voices can crowd out everyone else in an online space. In fact, this dynamic has led some public broadcasters in the past to give up on open online discussions altogether.

As we began narrowing down hundreds of concept sketches to a handful and refining them for development and testing with our public broadcaster collaborators, we chose to focus not only on strategies for preventing harmful content from crowding out all other contributions; equally important, we developed strategies for amplifying productive feedback loops that allow for more — and more various — groups of people to feel welcome and safe in online conversations. In other words, we designed for positive, constructive contributions to crowd in.

We applied these strategies across the canonical user journey. To offer a simplified version of this user journey: you need to first discover a conversation, you might then browse the conversation and what’s already been said, and finally you might interact with others — perhaps in lightweight ways by using emojis or upvoting someone else’s comment, and/or you might compose a comment of your own.

To reduce harmful content, we are implementing, testing, and evaluating the use of Large Language Models and AI-aided moderation of content as a tool to help ascertain if a comment or post that a user has submitted is in violation of community guidelines. We may use these same tools to subsequently help the user to express their experiences and viewpoints while respecting these guidelines.

To unlock productive feedback loops that create a more welcoming and safe environment, we are building and testing features that are deliberately designed to cultivate prosocial norms. One prototype in development, for instance, is designed to invite in missing or underrepresented perspectives on an issue. Several other prototypes nudge people to take more nuanced positions or emotional reactions beyond a binary.

Design for public conversations to take place across content and to be long-lasting

In our design process, we also examined and reconsidered common conversation models that exist on the internet.

On many news and media sites, the comments section is typically a free-form textbox attached to a specific article or individual piece of content. On many popular social conversation platforms like Reddit or Twitter/X, people can post and reply as many times as they want. There are drawbacks to these conventional conversation models: yoking a comments section to a specific article tends to limit its relevance — a discussion lives only as long as the news cycle. And unlimited posting contributes to the dynamic that we described above, in which the few loudest or most controversial voices crowd out other views.

In our work on Public Spaces Incubator, we have chosen to experiment with alternate public conversation models. The model that we will test in the upcoming months allows a conversation thread to span multiple public broadcaster stories, requires a guiding prompt or question written by editors, and takes inspiration from some aspects of town hall discussions.

How might this work? An editor at a public broadcaster could set up a conversation space anchored on a specific question, which audience members can access from any article associated with the topic. (As an example: imagine a conversation space anchored on the prompt, “Should Canada raise taxes to support social programs for the elderly?” and accessible from several entry points — from articles reporting on new policies for an aging population to human interest stories on how a particular local community is supporting its elders.) Within a conversation space, each audience member is allowed one response.

This paradigm is inspired by the town hall format, in which every participant is given, equally, one opportunity to speak within the allocated time, so that the discussion is not commandeered by the loudest or most aggressive. Over time, as public broadcasters add more reporting or analysis on the topic at hand, audience members can hop back into the conversation space and engage with the question anew by editing and refining their response, or by replying to others’ responses. In this way, we hope that public discourse on a topic has the opportunity to deepen and outlast the latest hot take.

Story adapted from CBC News, for illustrative purposes. Comments generated by ChatGPT.

There is still a lot to work out in this new model. How will the editorial process work with the workflows of different public media organizations? How do we treat identity and anonymity? How long should conversations last, and how do we reconcile stale replies as audience members refine their responses over time? As we continue to test our ideas, any of these design decisions might evolve, but we are giving ourselves permission to rethink the dominant conversation models on the internet from the ground up.

Design for public value, not just individual value

We believe that this project’s approach to design and product for public broadcasters has the potential to elevate public conversation to the same level of importance as the broadcasters’ world-class journalism. This might seem like a tall ask: directing audience members’ finite attention to participating in discussion could mean diverting their time and attention away from business-driven objectives like advertising (revenue) or account sign-ups (retention). But the public broadcasters’ mission to strengthen public conversation gives us the space to fully invest in these explorations.

Ultimately, investing in these principles means conceiving of “value” on the internet differently. Product development in the tech industry has traditionally aimed to create value for the individual user — but we have seen from Big Tech’s practices that user-friendly design and public-friendly design are sometimes in tension with each other. Often, this user-centric orientation is directed towards contributing economic value (sometimes called “exchange-value” in economics).

With our work on the Public Spaces Incubator, we hope to design for not just individual value or business value in service of the sustainability of these institutions, but also public value. This is notoriously difficult to pin down — fields like economics, politics, and philosophy have been debating its definition for centuries. Moreover, as a recent report from the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose points out, there is an inherent tension in defining and measuring public value for many public service media organizations: on the one hand, they are expected to demonstrate public value through traditional consumption figures used by privately-owned media organizations such as advertising revenue, number of subscribers, or subscription revenue; on the other, they have public service mandates — to inform, educate, and entertain — that run counter to this for-profit logic.

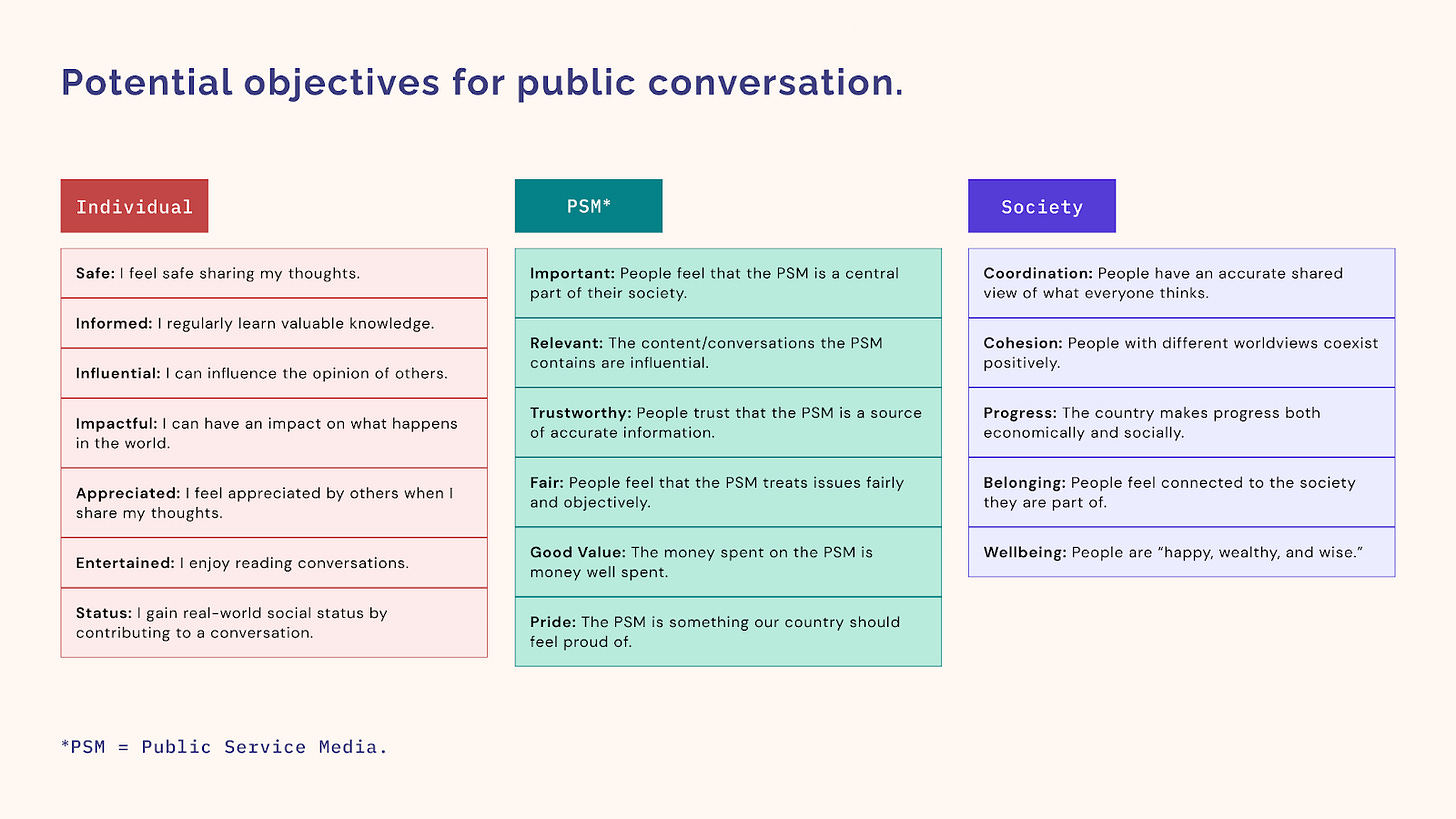

One way to address this tension is to acknowledge that our work, co-designed with audiences, can create value across three dimensions: 1) for individual people, as users and citizens, 2) for public service media, as organizations and institutions, and 3) for the public at large. Alongside our collaborators, and grounded in our research with audience members, we have begun developing a framework to situate our objectives and measure the outcomes of our work along all three dimensions.

Over the coming months, we will be building out more of our prototypes with our collaborators, testing them at increasing scale with even more users, and working to measure and understand their impact on public conversation. We look forward to sharing our progress as well as what we learn as we go along. Stay tuned!

— Victoria Sgarro, Lead Designer, and Min Li Chan, Senior Product Director

Such excellent and thorough work as always — I can tell I’ll be referencing this frequently ✨ It’s exciting to see others in our space converge on journalism as a key way to ground our work. (https://letsstudio.substack.com/p/on-journalism-democracy-and-design)

- The model you’re describing (inclusive conversations, over time, across content) was something that SF Chronicle prototyped using Discord through their SF Next initiative last year. Never fully took off, but definitely worth iterating on or talking to them about it.

- I’m also interested in the role of physical spaces, given the potential for stronger connection, inherent locality, cultural value, etc of a spot on the block. Are there places where these kinds of conversations about local issues are taking place, and if so, what can we do to augment and connect them? Is creating a new space helpful — and if so, how do you seed it? Currently exploring this in Oakland.

This reminds me of what I've read about Polis, a platform based on Taiwan's experience in generating consensus through discussion.

https://compdemocracy.org/Polis/