🧮 How to calculate the inclusiveness of online groups

Our new paper on Dynamic Polycentrism with the SNF Agora Institute

Along with our friends from ex/ante, we’re hosting a Happy Hour in NYC on April 10.

Our friends at Reboot are releasing the newest issue of their magazine, Kernel, and will be hosting their first-ever symposium to celebrate on March 23 in SF. We’ll be there, hosting a workshop. More info soon!

How do you know if an online community is healthy and interested in democracy? You can ask the community members about their beliefs and behaviors, but that can be complicated, time-consuming, and imprecise. How do you even know you’re asking the right questions? Is there any way to know in advance if a digital group is heading in an authoritarian direction?

With our friends at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and supported by New Pluralists, we’re releasing a new whitepaper with an important concept for measuring the pluralism of online communities.

This week: an interview with Hahrie Han of SNF Agora about our new paper on measuring pluralism

Don’t let the name “Dynamic Polycentricism” trip you up — this is about finding a way to assess the inclusiveness of a community, which can indicate whether it’s oriented towards democracy. As SNF Agora Director Hahrie Han explains below, this is crucial work, and this approach potentially offers actionable, measurable data.

Both this paper, and another, adjacent concept from SNF Agora and More in Common — what they call collective settings — examine how pluralistic communities, and the spaces they inhabit, have an important role in American civic and democratic life.

–Josh Kramer, New_ Public Head of Editorial

Taking stock of community pluralism

Hahrie explains her work at SNF Agora:

The SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University is an academic and a public forum dedicated to trying to strengthen democracy all over the world, with a particular focus on the notion of the agora as being foundational to making democracy work.

The ancient agora in Athens was the place where people gathered — they went shopping, they discussed politics, they got to know each other. The agora-like spaces we inhabit nowadays have been transformed in radical ways since ancient times.

And those transformations matter for making democracy work. Alexis de Tocqueville is a French philosopher who came to America when it was still a nascent democracy to learn what made it possible. When he visited, he was like, “What is going on here? All the people are like joining things, all the time.” He was surprised to find that Americans get together all the time — to drink beer, go bowling, plant neighborhood gardens, to do all the things. And that, he argued, was part of what made this crazy democratic experiment in America possible.

We have a really rich and robust history of strong civil society organizations that always worked alongside government and the market to form society’s three-legged stool. But now, in too many places, civil society has been really hollowed out. In places it’s moved entirely online, and in other places it’s some combination of both.

Why bringing people together in communities is not enough:

What we know from history is that civil society, or these “great free schools of democracy” that Tocqueville described, can be carriers of either authoritarianism or democracy. When you bring people together in these civic communities, historically we have found that they can either facilitate the “small d” democratic outcomes that we want, or they can actually facilitate authoritarian outcomes.

The most notable example is work by a scholar named Sheri Berman where she documents the ways in which civil society was actually really vibrant and very thick in the years leading up to the Weimar Republic. And in that case, it was a carrier for Nazism, which obviously is not something that we want to see repeated in history.

So the big question is, how do we know ahead of time which civil society organizations are going to be carriers of democracy and which ones will be carriers of authoritarianism? We can look back retrospectively and say with a hundred years of hindsight that we know that the Weimar Republic was not good civil society.

But really what we want to be able to do is look around and say, “here are the groups in America that are really going to strengthen and facilitate our ability to have a common democratic project. Whereas, here are the groups that are actually hindering our ability to have a shared democratic community.”

Pluralism is the secret sauce of democracy:

Pluralism is built on the reality that no two people are ever going to have the exact same goals and interests and desires in the public sphere. There are inevitable differences between people who are trying to create a shared community. People are going to disagree. But pluralism is about creating a process, and a set of institutions, and a culture, that enables those disagreements to be productively channeled so that we can make agreements about how we want to share resources and how we want to create a life together.

One of the things that we've always known from the very earliest days of democracy, is that people are not born with the capacities that it takes to live in a pluralistic democratic society. Humans are naturally shortsighted and self-interested and we like to hang out with people who are more like ourselves, and we have all these shortcomings that makes it really hard to live together in a pluralistic community.

That’s why Tocquevillian “schools of democracy” are so important — the audacious promise at the heart of democracy is that by working with each other, people learn the motivations and capabilities they need to work with each other, navigate difference, and live together in a pluralistic society.

Why is it difficult to measure pluralism?

One of the really hard things about measuring pluralism is that you don't know ahead of time what lines of division are going to divide a community. So certainly in America, there are lots of structural inequities that lead to common sources of divisiveness. Race, class, gender — these are all issues that, because of structural inequities that exist in society, often lead to areas of divisiveness. But we also have others that you wouldn't necessarily be able to anticipate.

For example, right now we live in a very polarized era — partisanship is another axis of divisiveness. If you had asked me two years ago, what’s the issue that's going to be most divisive on college campuses today, I'm not sure that I would have said Israel/Palestine issues. Yet that is, in fact, the issue that's tearing a lot of college campuses apart right now. It's not that we didn't know that there's disagreement around Israel and Palestine, but it hadn't come to the forefront in such a way that it was threatening the pluralism of particular communities.

That's the challenge that makes measuring pluralism really hard — we can’t always anticipate what the lines of difference are that we should assess. The challenge of measuring it ahead of time is trying to figure out, how do we assess how pluralistic a community is without knowing all the different ways in which people might disagree?

The advantages of using “polycentrism” to measure pluralism:

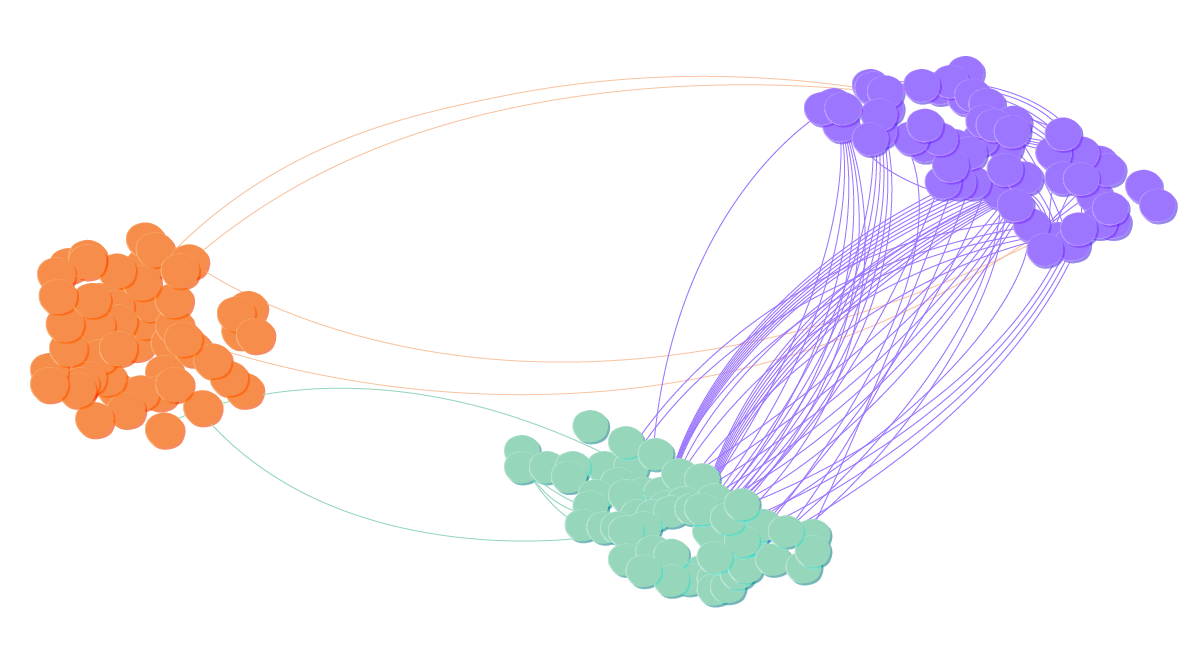

Polycentrism is an idea that was made famous by work from Elinor Ostrom, who was the first woman to win the Nobel prize in economics. She and her husband did a lot of work on polycentrism. Basically it's the idea that healthy communities have multiple nodes of power that sort of exist in decentralized ways. So it's not just a centralized community, but it's a poly-centralized community — there’s many centers, essentially. And those communities have certain advantages.

In the context of what we're talking about here, the particular advantage is that you do not have just one person, or one group of people, who are in charge and may or may not be reflective of the many different ways in which a community is pluralistic. It’s that you have lots of these different nodes, spread out throughout the community, that each have their own center of gravity.

We anticipate that a community that has lots of different centers of gravity spread throughout it is going to be more flexible and able to adapt to divisive challenges that might come its way, because those centers of gravity can flex and flow with the challenges that emerge. That’s why polycentrism is important to pluralism.

What makes a polycentric community dynamic?

It’s dynamic if who makes up the nodes, and how those nodes are relating to other people in the community, are constantly changing, so that it’s not the same people accruing and ossifying power over time. The ways in which people are tied to each other are dynamic, in other words. You’d anticipate that those kinds of communities are more likely to have the flexibility to be able to adapt to kind of the pluralism that we would want.

The advantage of thinking about dynamic polycentrism as a measure of pluralism, is that we have a lot of the data on it, particularly in digital communities. We can actually observe the structure of the networks in these communities. It's an observable, attainable measure that gives us a hint about the likelihood of communities to be truly pluralistic or not.

This measure of pluralism is useful because we can look at communities that seem to be trending in less polycentric or less dynamic ways, and try to make interventions to forestall undemocratic outcomes that we may not desire.

An example of dynamic polycentrism in action:

The best example I have is an offline example. I have done a ton of research with evangelical megachurches in America. The church that I've done the most work with is a church that gets 35,000 people to show up each week and about 500,000 people attending online. There are very few organizations that can get 35,000 people to show up each week to anything.

The building block of megachurches in America — not just this one — is what they call “small groups.” Essentially they’re self-organized, self-governing groups that get together. It might be anything from ten people who want to do a Bible study, to people that want to go rock climbing on Friday nights, or new parents who want to find a community of support within their church. They self organize around a range of different kinds of topics and interests and reasons to get involved, and they’re self-governed, so they decide together: how are they going to structure their Bible study? How often and where are they going to meet? When they do get together as new parents, what are the topics they're going to discuss?

That essentially creates all these polycentric nodes of people who have organized these small groups. And they’re dynamic, in the sense that small groups tend to shift and flow over time as people move in and out of different small groups. And what research has shown is that megachurches are at the growth edge of churches in America. Something like 90% of megachurches use small groups, so they have that sort of natural polycentric structure to them that enables you to be both intimately connected to a small group of people, but also part of a much larger community.

What’s next for dynamic polycentrism?

The whole idea of dynamic polycentrism is still a hypothesis. We're trying to assess whether or not it's a good ex-ante, anticipatory measure of how pluralistic a community can be or not.

At the SNF Agora Institute, we recently completed a project that we called Mapping the Modern Agora. Basically we use a lot of data science to map civic infrastructure in the United States. But we don't know what kind of community is inside those organizations, and so that's the data that we need, both in formal geographic civic entities, but also within digital communities, because we know that people are as active in digital communities as they are in non-digital communities.

Community stewards should consider how dynamic, polycentric, and ultimately, pluralistic their community is. Builders should contemplate optimizing for these metrics as they develop new social products and spaces. Are there design features that ensure a multiplicity of different kinds of voices?Thanks Hahrie! Reach out in the comments below if you’re interested in testing dynamic polycentrism in your community.

Reminder: New_ Public and the Center for Media Engagement want to know more about what excites online leaders, the role they play, and the challenges they face. Your insights will help us better support community leaders. Participants from our quick survey will be randomly selected to receive $25 gift cards.

Happy to see daffodils opening,

Josh

Yes, this idea of dynamic polycentrism is a very promising direction for re-forming social media.

Very much in the spirit of part 3 of my series in Tech Policy Press with Chris Riley: Community and Content Moderation in the Digital Public Hypersquare (https://www.techpolicy.press/community-and-content-moderation-in-the-digital-public-hypersquare/).

And for an outline of how we can make that can take shape, see A New, Broader, More Fundamental Case for Social Media Agent "Middleware" (https://ucm.teleshuttle.com/2023/11/a-new-broader-more-fundamental-case-for.html).

The idea is that human discourse and society have always been organized by a “social mediation ecosystem” that is dynamically and organically polycentric. We need to re-form social media to support that, not destroy it.

Are you aware there was a second public space for democratic discussions in ancient Athens, the Pnyx, with very different public architecture of the space? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pnyx

The shape https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_Pnyx_colored.svg is more similar to Senate or second chamber parliamentary buildings in some states now. I've been noticing how the shape of a space influences people's social psychology and thinking about this since 2016, and recently came across this special collection in European Journal of Political Theory which aligns with some of my hunches- van Leeuwen, B. (2024). Is architecture relevant for political theory? *European Journal of Political Theory, 23*(1), 116-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/14748851211063672