Can New Zealanders trust an automated government?

‘Algorithms work best in conjunction with relationships.’

Much ink has been spilled this year about digital infrastructures that might let people make decisions, transact, and play without needing to know or trust each other. Over in the febrile waters of web3, small groups plot new organizations where decisions will be automated through smart contracts. In the fustier offices of government bureaucrats around the world, people consider whether laws and regulations could be made machine readable, enabling more decisions to be automated as code becomes law. Trust in institutions and government may be low, the logic goes, but perhaps we can trust computers instead.

These experiments are part of a broader trend of people exploring how technological systems can support new models of organizing people, money, and activity. But in the process of automating complex processes, automated decision-making systems and “trustless” infrastructures alike risk making complexity invisible and recourse impossible, further entrenching existing inequities and alienating already-underrepresented people.

In this essay we focus on automated decision-making deployed by governments, whose decisions around automation and AI have far-reaching consequences. And we know that people are concerned—because we asked them.

In 2020, we were part of a research project looking at trusted and trustworthy and automated decision-making in Aotearoa New Zealand. In the course of the project, we heard from 187 people from around the country about how automated decision-making affects their lives, how they feel about it, and what could be done to make them feel more comfortable. The research project was led by the Digital Council for Aotearoa New Zealand, an independent advisory group to the Minister for the Digital Economy and Communications, with the participatory research conducted by Toi Āria’s design research team. We, the authors of this piece, drafted the final research output, bringing together findings from the participatory research, a literature review, and a report from Māori experts into a report to the Minister with recommendations to the government.

In the past few years, there has been significant discussion in New Zealand about the role of algorithms in decision-making—particularly those deployed by government agencies—with a focus on ensuring fairness and transparency. In 2019, the government released a stocktake of operational algorithms used across agencies, and in 2021 the official statistics agency Stats NZ released the Algorithm Charter for Aotearoa New Zealand, outlining guidelines for participating government agencies in their implementation of medium and high-risk operational algorithms.

Unlike previous work on algorithms in New Zealand, and much of the broader research on trust and automated decision-making, our project with the Digital Council prioritized hearing from folks who are often impacted by complex digital systems but rarely have agency or input into their design. We heard loud and clear from participants that they are doubtful the current approach to automating important processes will lead to more equitable outcomes, even if the automation is intended to reduce human bias or make the decisions more trustworthy. But we also came away with important insights about how institutions that use automated decision-making can improve—and it starts with including people in the process.

Relationships come first

Our research team knew we wanted to hear about trust and automated decision-making from people whose voices aren’t usually heard on the topic. Research participants included young people with experience in the care system, Māori and Pacific youth, blind and vision impaired people, and migrant and refugee women. But to begin talking about trust, we had to build trust—especially as we wanted to hear from folks who’ve had their goodwill and capacity drawn on so many times before by researchers, government and nonprofits, with little reciprocity or progress to show for it. That meant forming relationships with people from the communities we hoped to hear from, communicating transparently and consistently, and making people feel that their words would be heard, understood, and respected.

Eventually we all made it into the room together. Workshop sessions were held in community centers, offices, and Zoom rooms around New Zealand. Each workshop focused on participants from a different group or community, and each started with a welcome, introduction, and shared kai (food). People split into small groups, and with the guidance of facilitators, discussed a set of scenarios in which algorithms played a key role in a decision-making process. The scenarios ranged from low-stakes situations like having a film suggested by a recommendation algorithm, to high-stakes situations like automated risk-assessment instruments that inform parole decisions. They largely focused on the government’s use of automated decision-making where the decisions had significant impacts on people’s lives.

You can’t automate your way to trust

For years, academics and activists including Safiya Noble, Cathy O’Neil, and Joy Buolamwini have written about the potential for algorithms and automated decision-making systems to be developed and used in ways that embed and perpetuate systemic biases and racism, or the individual biases of the people building the technology. Many of the people we heard from pinpointed these same issues, and were wary that automated decision-making systems would do nothing to help remedy the systemic bias or demeaning bureaucracy many of them often faced in interactions with the government.

Algorithms are only as good as the people who designed them. Machine learning might help with that, but right now most of the algorithms are people-designed, so people’s individual biases … can come into play.

—Blind and vision impaired workshop participant

People from poorer and minority communities are also well aware that data collected about them does not reflect the full picture of their lives and aspirations. People experiencing poverty are required to give up copious information about their living situations, spending, and family lives in order to access services like welfare and housing assistance. But when these data sets are used to inform algorithmic decision-making processes, it can feel like you’re forever defined by past challenges.

Who wants their life to be based on stink stuff from their past, that came from things from their parent’s past that they had no control over? Stop focusing algorithms on what you think is the matter with us. Instead focus them on what matters to us, the changes we want to make. Ask us, and start collecting that data.

—Whānau Ora navigators workshop participant

It didn’t come as a surprise that folks we heard from had strong and perceptive opinions on data and bias—people with lived experience of discrimination often have to also become experts in the government systems they’re required to navigate.

As well as noting that algorithms might encode the biases of the engineers and organizations that design them, people were quick to identify that the datasets that train algorithms and inform decisions are likely to reinforce historic patterns of discrimination and selective measurement.

While discussing a scenario where automated decision-making was used to inform parole decisions, one workshop participant said, “This is the justice system and I can’t imagine a training set that didn’t come from past decisions. … [Assessments about a person’s] risk of offending would be based on data on reoffending which is based on getting caught, getting convicted—which we already know has got a huge amount of bias in this country—so it would just self-perpetuate.”

While algorithms and data sets are central to the function of an automated decision-making system, solving for bias in algorithms and building better data sets will not be sufficient to solve the trust problem. “It’s not whether the algorithm is testing what it’s supposed to test, it’s what they’re doing afterwards,” one young person with care experience told the team. People clearly saw algorithms and data as just one small component of a wider system of system design, governance, and organizational culture.

We shouldn't separate the system and the algorithm because, for something to work, we have to consider both. It has only ever been designed to be part of the system.

—General public workshop participant

A trusted and trustworthy digital system requires users to have trust in the organization building and maintaining that system. And when that organization is a government agency, for many people the trust just isn’t there. A significant number of the people we heard from—and especially Māori, Pacific and blind or low vision people—had very low trust in scenarios where government departments used algorithms for high-stakes decisions.

This distrust has complex historic reasons. For Māori in particular, distrust in government decisionmaking is informed by the history and ongoing experience of colonization. In their contributing report “Māori perspectives on Trust and Automated Decision-Making,” the Te Kotahi Research Institute authors noted that “the whakapapa of distrust is rooted in a broader distrust of the systems in which ADM’s [automated decision-making systems] are embedded.” Work to build trust in government decision-making will necessarily start with work to address the root causes of this distrust. As the authors state, there is “no current incentive for Māori to trust the systems in which ADM may be employed.”

In the course of our research, we learned from Māori experts and workshop participants that the project’s framing and key research question—which centered questions and concepts of trust—wasn’t well suited to enable the issues to be discussed from Māori perspectives. The word “trust” does not have a commensurate word in te reo Māori, nor is the Western concept of trust the key issue for Māori when it comes to navigating relationships and power. Researchers at Te Kotahi emphasized “the importance of being able to frame questions in ways that align with Māori concepts and values, allowing for discussion and debate within a te Ao Māori view and from the point of view of Māori interests”.

This disjunct prompted us to reflect on the need to design research engagements around participants’ cultural values and ways of working, and emphasized the limitation of “trust” as a framework for understanding relationships, technology, and power.

Toward something better

So how can the state—or other organizations that provide services or spaces for a broad public—build digital systems and employ automation in a way that doesn’t further disenfranchise people? From what we heard in our research, a key to building people’s comfort with automated decision-making is summed up in the disability rights and participatory democracy rallying cry: Nothing about us without us. “We want to see Iwi, hapū, whānau involvement in creating them [systems]. Co-develop the solution,” said a Whānau Ora navigator participant.

The people directly affected need to be consulted about the criteria being written for the algorithm and definite checks and balances are needed, reviewing and monitoring them, and also that things are being created to take into account social disadvantage.

—Blind and vision impaired workshop participant

Despite strong feelings of discomfort towards many automated decision-making scenarios, most people weren’t opposed to all uses of automated decision-making, even by a government they had little reason to trust. Some decisions were considered simple or low-stakes enough that automation was appropriate, and might help speed up previously-slow processes. People could also clearly imagine how automation could be mobilized in equitable, even liberatory ways, if conditions were different and if systems were designed in a way that included them. “If you want to know an area that an algorithm could help with, find an area that actually matters to famil[ies],” one Whānau Ora navigator participant said. “Create the algorithms around that—what makes up a happy person, a happy whānau,” said another.

People also wanted to see more transparency about when automated decision-making was being used, how it worked, what data and criteria were used to inform decisions, and what part it played in the wider system. They wanted to see this transparency accompanied by clear and open communication that made space for asking questions and opportunities for recourse if something did go wrong. The ability to talk directly with a person, not just a chat bot or via one-way missives from an organization, was also seen as an essential part of building trust through community.

Algorithms work best in conjunction with relationships.

—General public workshop participant

Ultimately, we learned that digital projects and systems are likely to succeed or fail, build trust or diminish it, because of the relationships involved.

Postscript

The Digital Council presented their report to Minister David Clark in late 2020, and launched publicly in 2021. Although our work on the project finished over a year ago, the insights from the research have significantly shaped our thinking about trust and digital technologies and our approach to research and design more broadly. We have more trouble than ever imagining a scenario where trust in institutions could be replaced with trust in a technical system. And we have more appreciation than ever for the hard work of communities and activists who fight to be heard and included by designers, organizations, and governments who so often (despite frequent good intentions) build digital infrastructures that disregard people’s best interests or even cause harm.

Automation allows for increased speed, scale, and sometimes immutability, all of which can have huge benefits—especially for people profiting from the efficiency gains as a result. But without taking steps to build trust over time and involve users and diverse teams in design, trust in digital systems will remain unevenly distributed. Privileged people will likely trust that systems will serve them while less-privileged communities have little choice but to engage with digital infrastructures they don’t trust but which define the course of their lives.

If governments and organizations want to have trustworthy systems that truly serve a broader public, sometimes decision-making needs to be slowed down to a human scale, with the space to make adjustments to account for the needs of people affected. Because you don’t build trust with technical systems. You build trust through relationships. 🌳

Kelly Pendergrast is writer, researcher, and sometimes art worker based in San Francisco. She is the co-founder of Antistatic, a consultancy that focuses on complex issues around technology and the environment. Her writing has appeared in Real Life magazine, e-flux, and Business Insider.

Anna Pendergrast is a writer, strategist and policy analyst based in Wellington, New Zealand. As co-founder of Antistatic, Anna helps people communicate about the complex issues they are working on in order to drive positive social and environmental change. Much of her recent work has focused on digital technology and data systems and their impacts on individuals, communities and the environment.

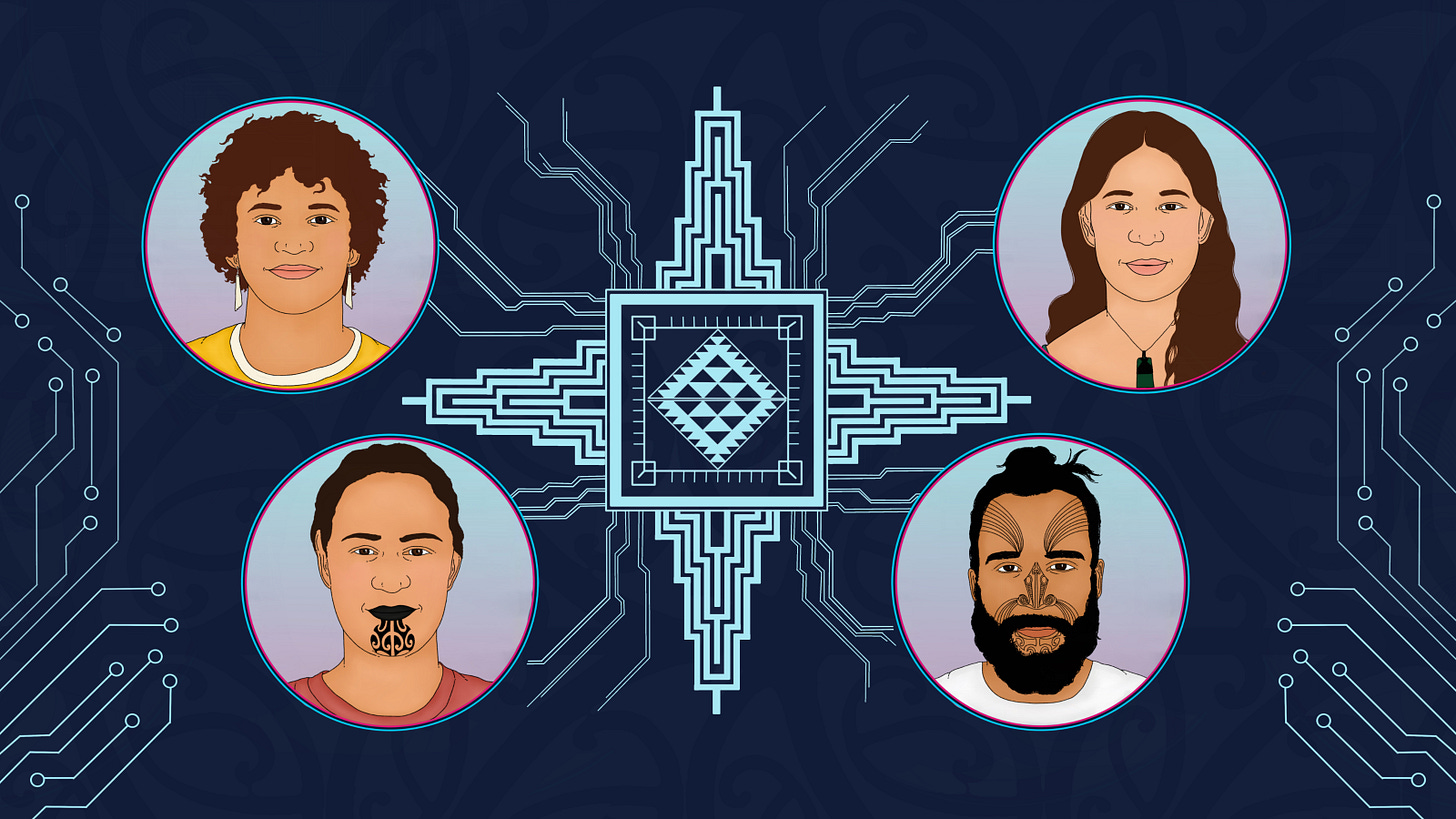

Illustration by Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho.