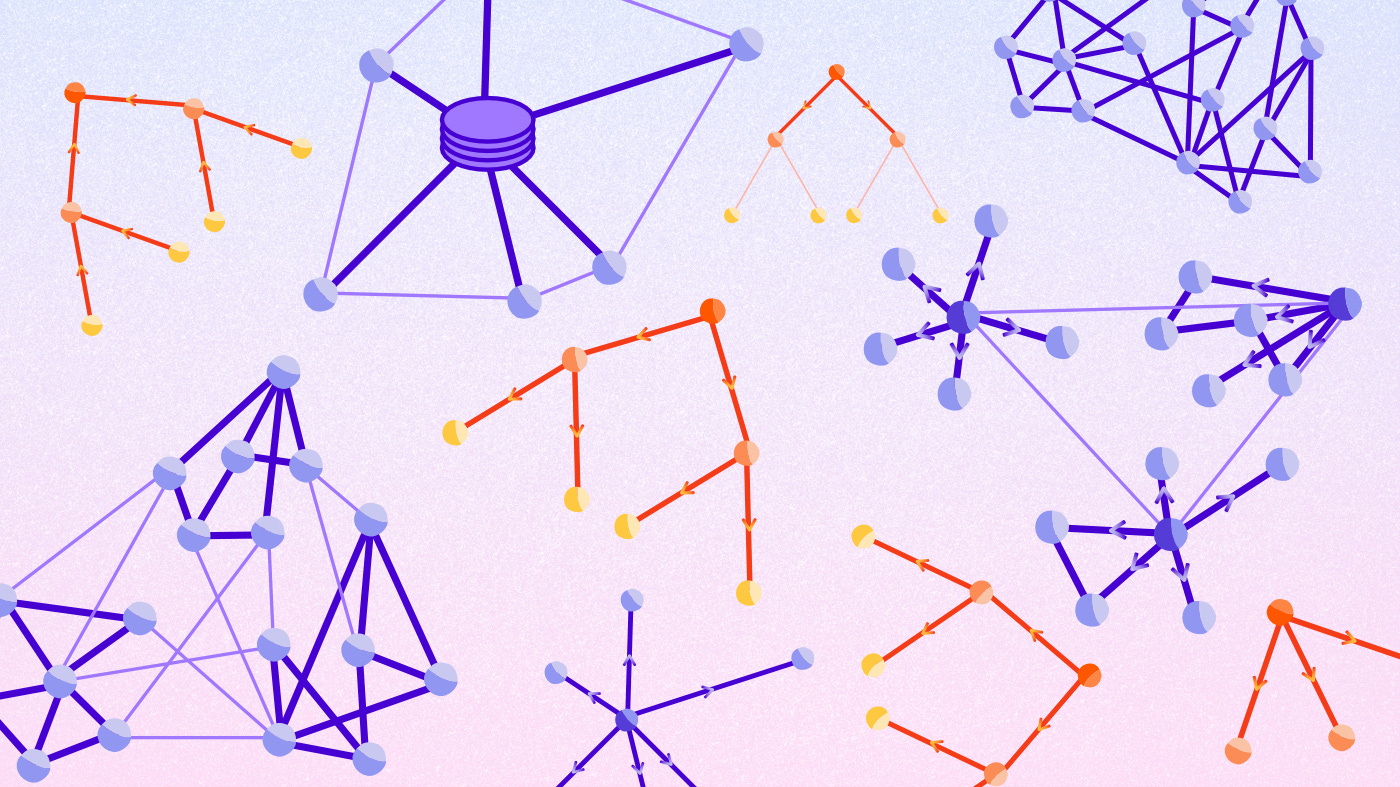

A visual guide to decentralization

From nesting to networking: forms of decentralization according to Nathan Schneider

Here at New_ Public, we’re interested in the evolution of digital public spaces—where communities can find themselves and flourish online. As a result, we think about structure and organization quite a lot, including the concept of decentralization. Take public parks, which we see as a useful analogy for internet commons. On one level, parks may appear decentralized: with unsupervised users observing norms and functioning responsibly and respectfully. However, as we find to be true with many so-called “decentralized” models, there is often centralization at work: a mosaic of taxpayer-funded institutions regulate, maintain, and even police parks.

To further explore this tension, we turned to University of Colorado Boulder professor Nathan Schneider, author of the article “Decentralization: An Incomplete Ambition,” published in the Journal of Cultural Economy in 2019. Schneider found that there are distinct models of decentralization in the domains of political science and computer networking—each with their own gray areas and contradictions. Decentralized structures, Schneider suggested, are not set in stone, but can change over time. To quote the Satoshi Oath, Jaya Klara Brekke’s proposed code of conduct for developing on the blockchain: “one version of decentralisation might clash with another, and if it becomes compulsory to take part in a decentralised system, the system itself becomes an oppressive authority in its own right.”

This visual guide, based on Schneider’s paper, describes some of the more notable forms of decentralized networks. As you consider the investigations of decentralization in this issue of our magazine, you may reflect on the models here and how they match—or diverge from—what you encounter.

Hierarchical nesting

“A theory of decentralization must include a theory of centralization as well,” wrote Schneider. So let’s start here, by thinking about when centralization works, and why.

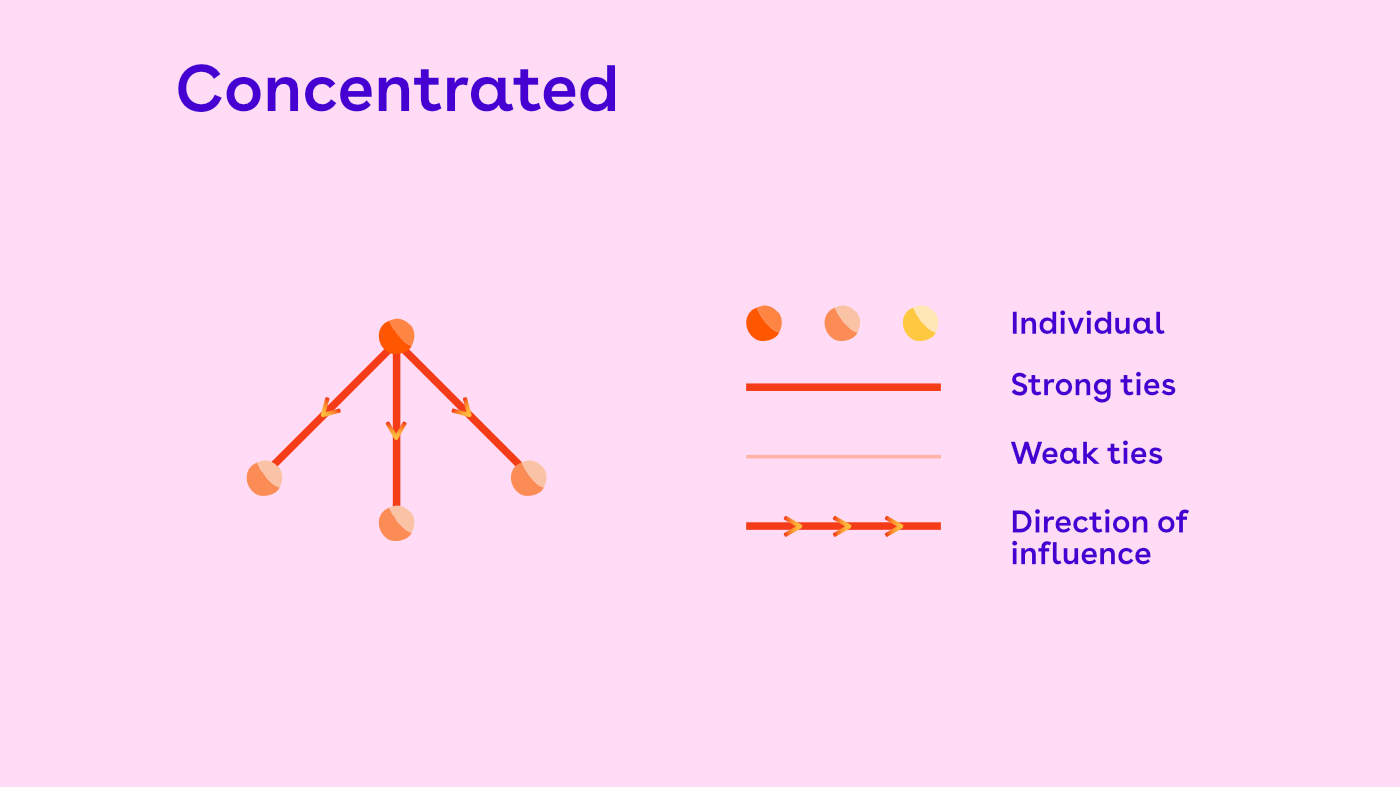

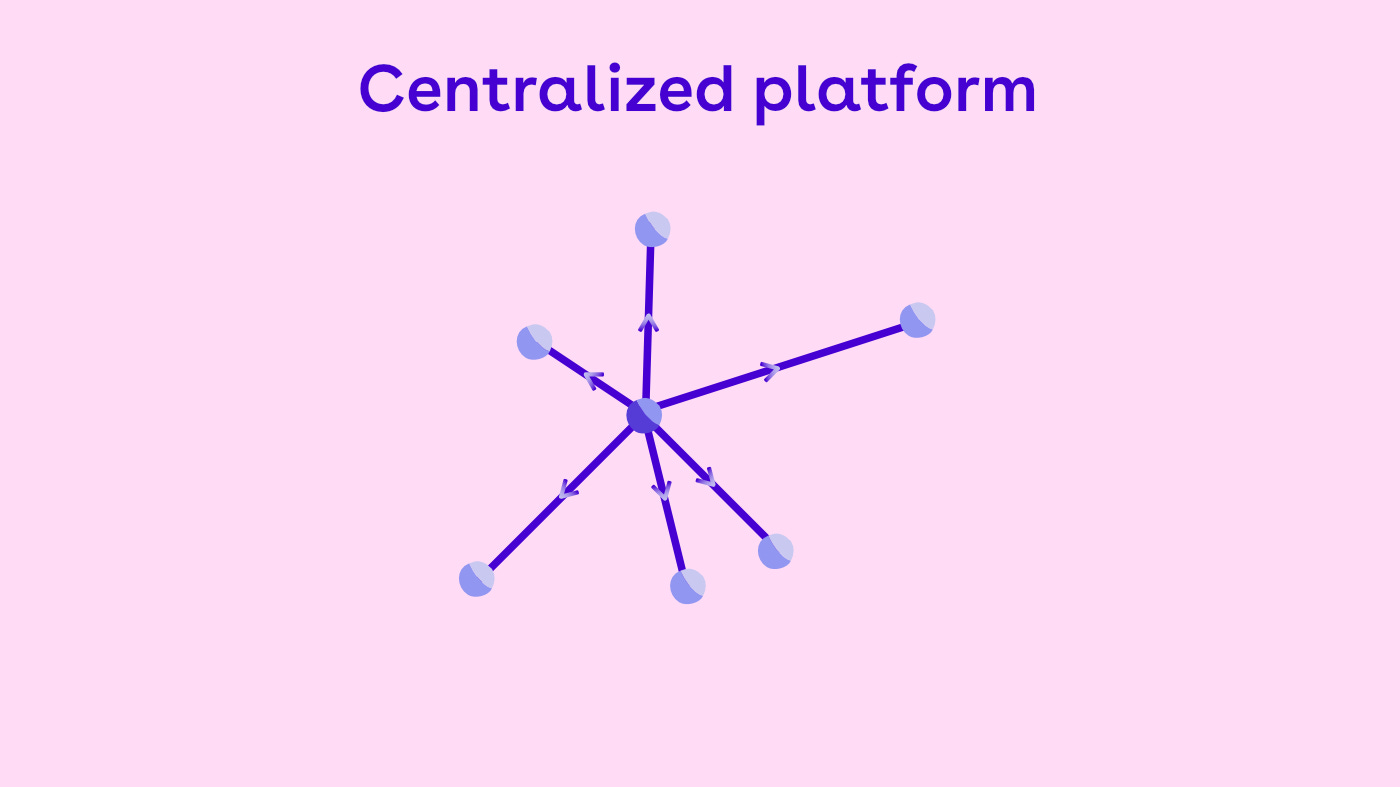

Centralized / Concentrated Structures

According to Schenider, “Centralized structures can have virtues, such as enabling publics to focus their limited attention for oversight, or forming a power bloc capable of challenging less-accountable blocs that might emerge. Centralized structures that have earned widespread respect in recent centuries—including governments, corporations, and nonprofit organizations—have done so in no small part because of the intentional design that went into those structures.”

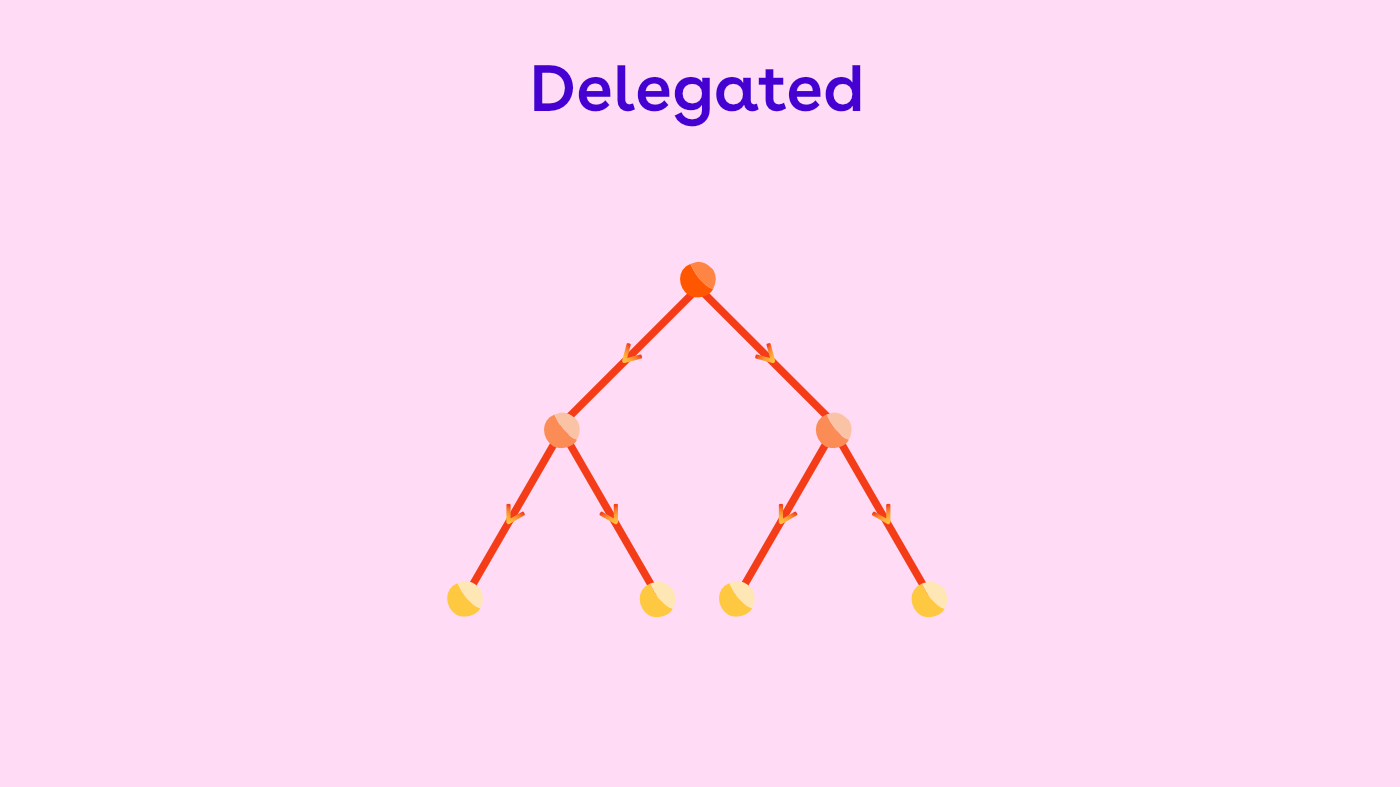

Delegated Structures

A delegated structure, where, for example, an individual empowers her subordinates to operate with some independence, is another form of decentralization. Delegation does not aim to eliminate the central authority. It’s a common management style, often a concession to the demands of keeping a complex organization running smoothly.

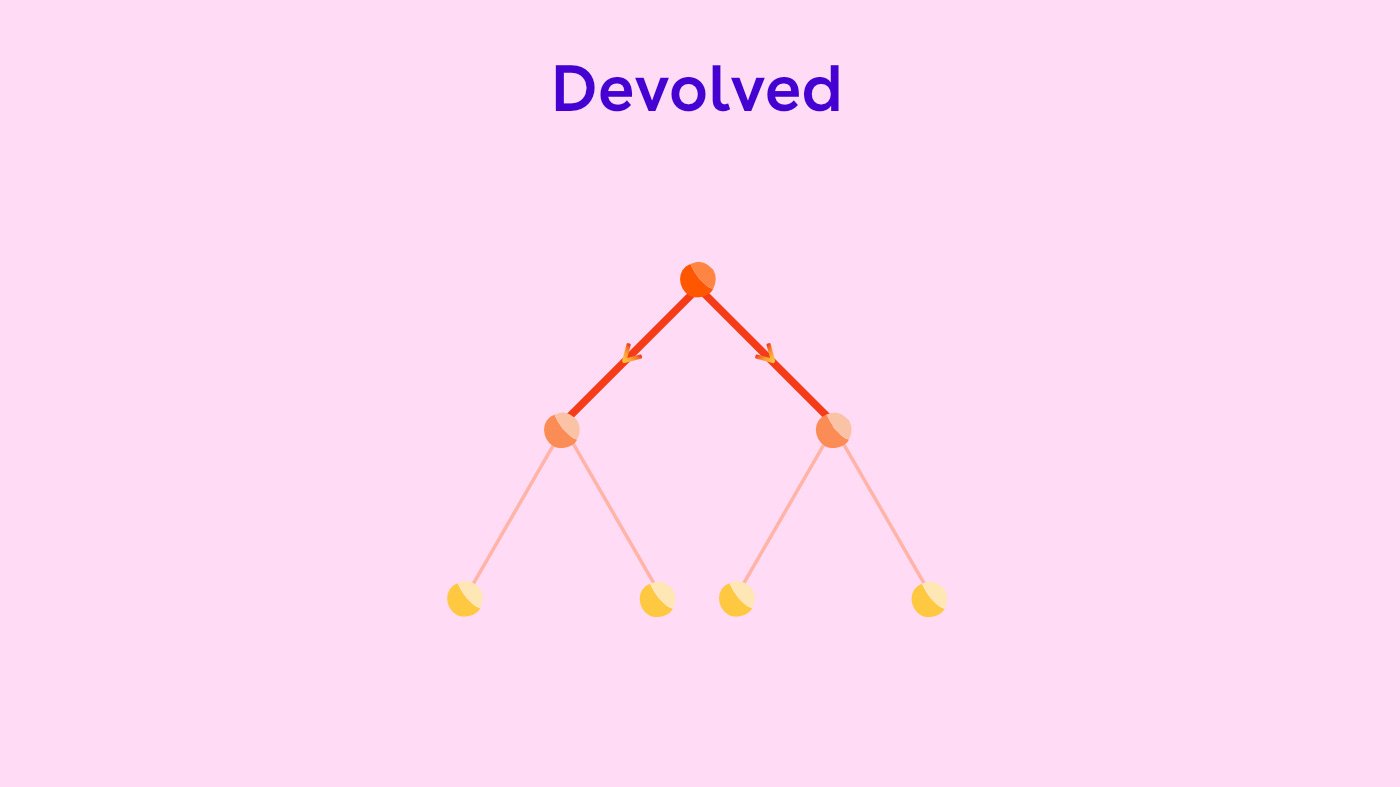

Devolved Structures

A devolved structure is “more” decentralized than a delegated one. According to Schneider, “devolution can involve significant local autonomy from a national government (e.g., in Spain’s Basque region) or even full national independence (e.g., the secession of South Sudan).” In the diagram, the nodes at the bottom are now connected to the central authority through weak ties instead of strong ties.

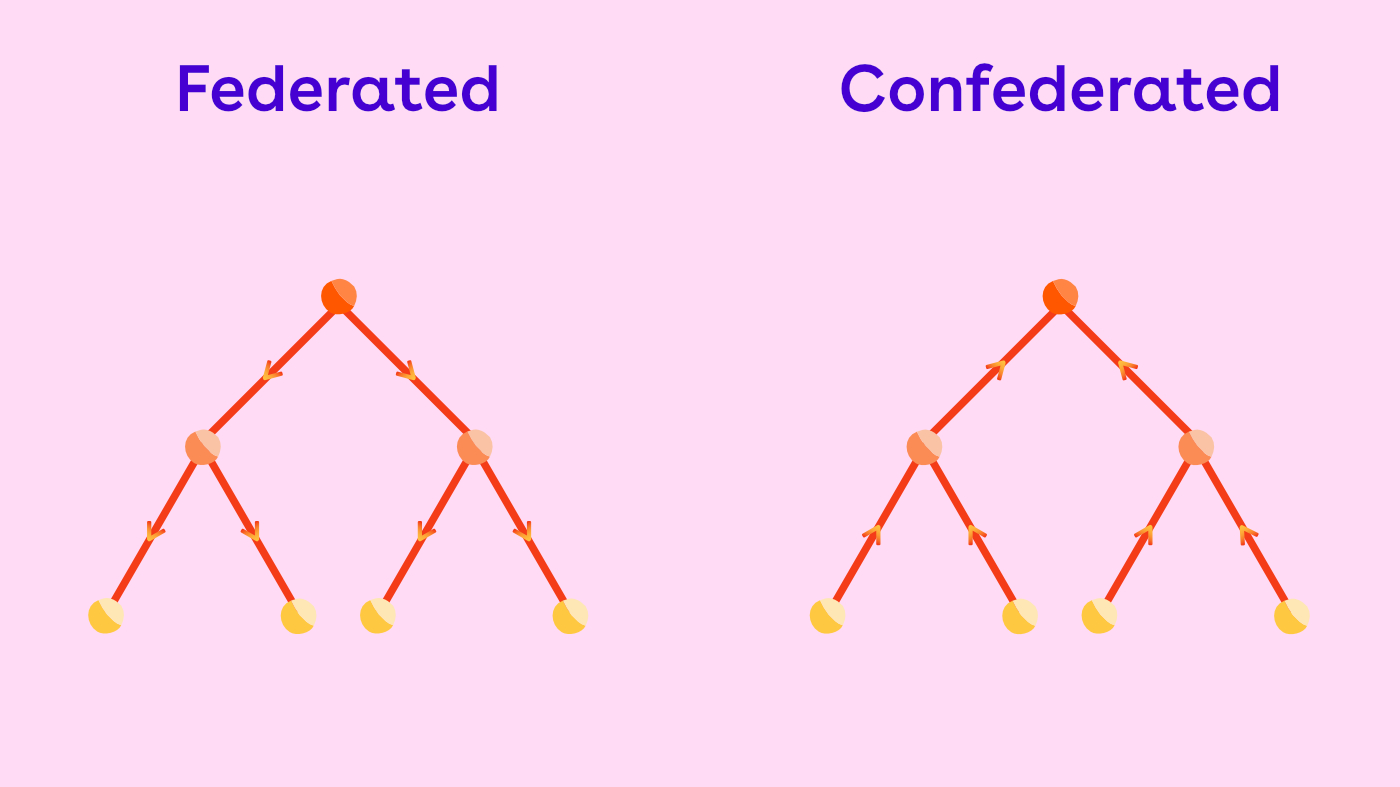

Federated / Confederated Structures

“A governmental pyramid may be federated (where sovereignty resides primarily in the central authority) or confederated (where sovereignty resides primarily among constituent members),” wrote Schneider, “but one way or another, international politics expects a head of state.” For example, the (modern) United States is federated, whereas the European Union is confederated. Pick your favorite example—these models of governance are still familiar the world over.

Peer-to-peer networking

As Schneider wrotes, “Fears that the decentralized Internet might become somehow centralized date back to its early days.” For creators of the modern internet, including Tim Berners-Lee, these concerns were focused on institutions of the late '90s: the Domain Name System and the organization ICANN. But now, a few firms (Google, Facebook) see the majority of web traffic in the US, a few companies host the majority of the data (AWS, Cloudflare), and a few telecoms operate the majority of the infrastructure (Comcast, Verizon).

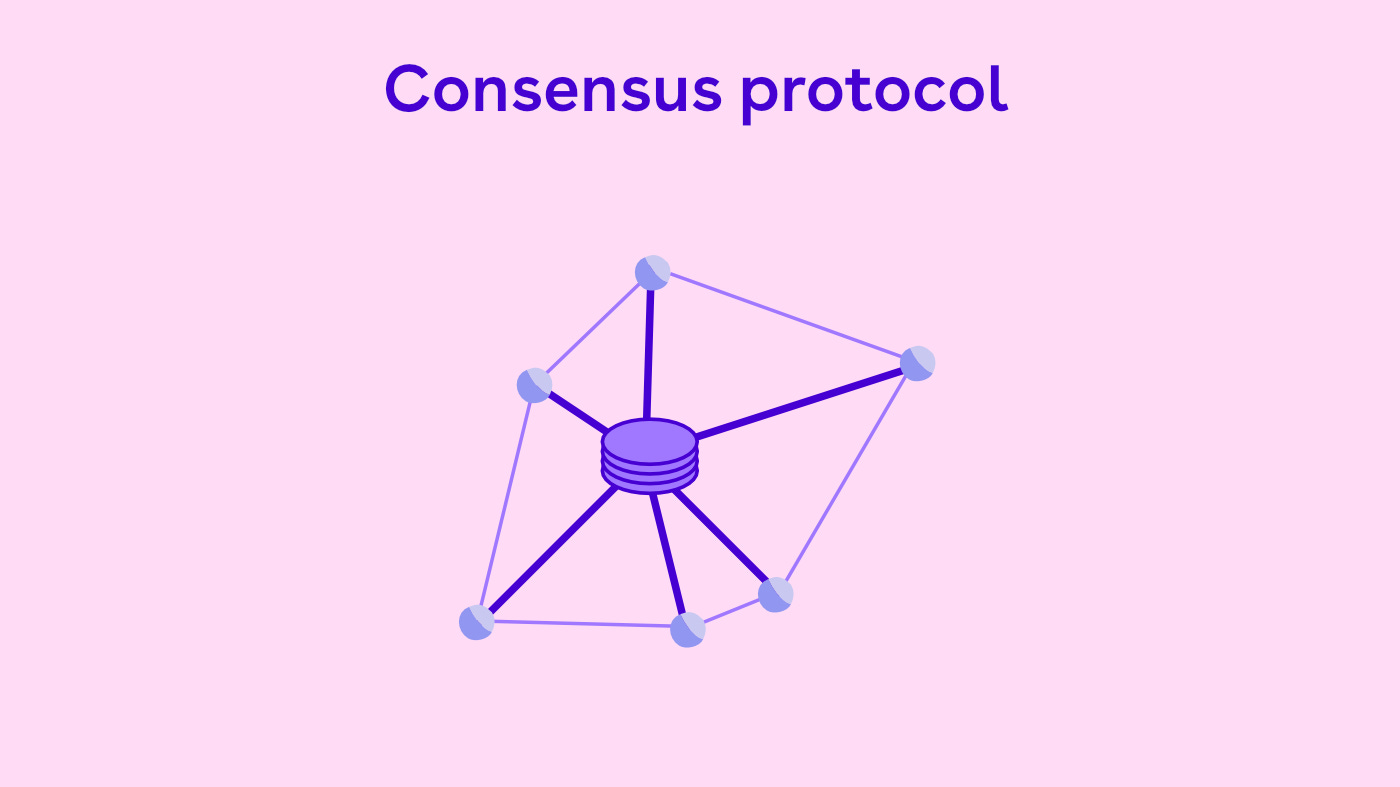

Consensus Protocols

We’ve finally reached the blockchain. With no centralized authority, the control of a blockchain system is distributed throughout a network. But is a blockchain completely “decentralized?” According to Schneider, summarizing Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin, consensus protocols like Ethereum “are architecturally and politically decentralized, but logically centralized, since they maintain a universal ledger based on the ‘consensus’ of peers in the system.”

Mesh Networks

In this idealized network, each node only communicates with the other nodes near it. Schneider described such a network as a “maximally redundant and egalitarian distributed mesh.” The basic structure of internet traffic borrows from this concept. But does a structure like this truly exist anywhere? It’s hard to realize a real-life network with no centralization whatsoever.

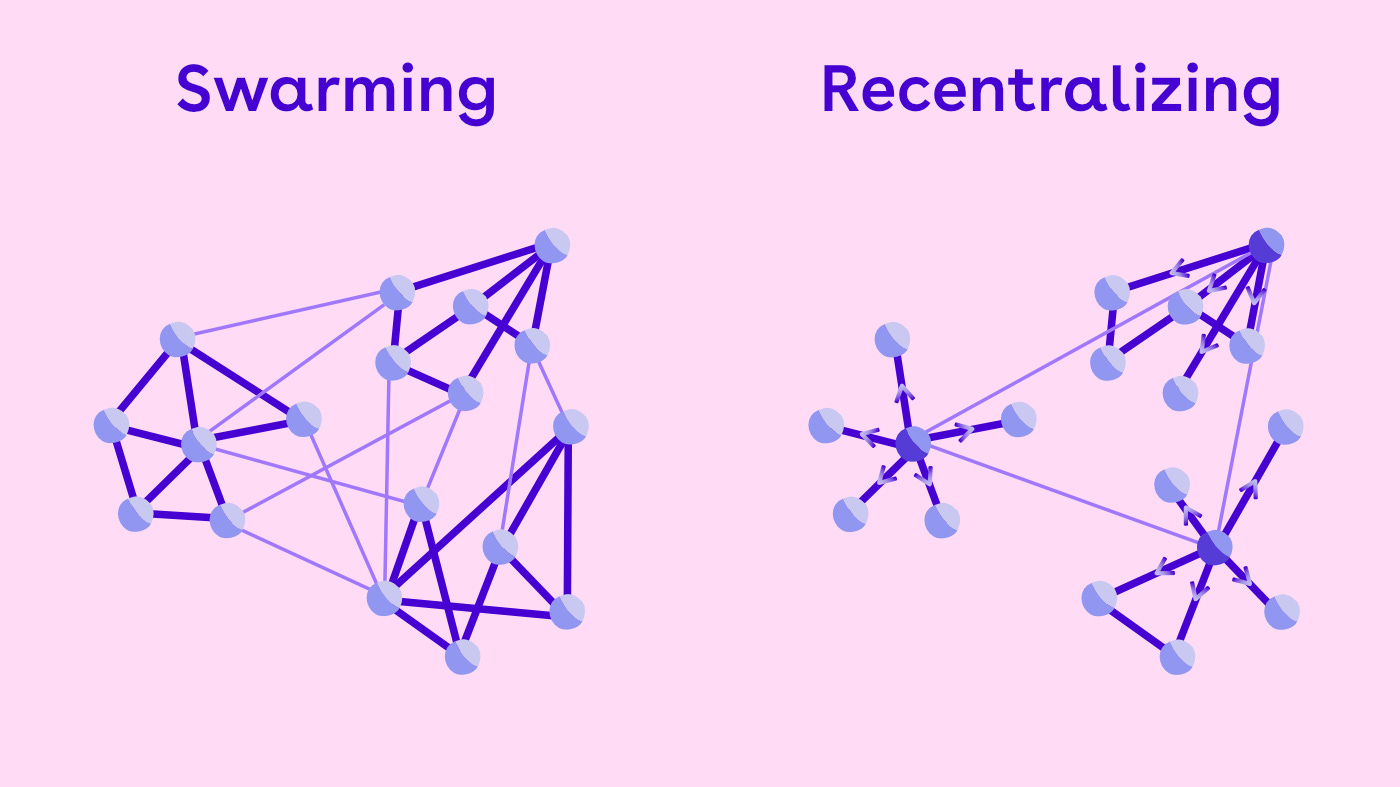

Swarming and Recentralizing Networks

Even highly distributed networks have a tendency toward reorganization. One of those transformations, according to Schneider, is swarming, which “refers to self-organizing, anti-hierarchical behavior among groups.” Notice how the mesh network in the swarming diagram is organized in clusters, with weak ties connecting those clusters.

A mesh network might also recentralize into something that resembles a few clustered, centralized networks. As Schneider noted, this whole process may itself be an illusion: “The center never departed in so many cases where we hear the cry of decentralization—it only shifted and took time for proper reconstitution. The shift was not noticed because people were too busy speaking of decentralization.” 🌳

Josh Kramer is a cartoonist, illustrator, and journalist living in Northeast Washington, D.C. His art and writing, often focused on cities and transportation, has appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, and CityLab. Josh was a 2017 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan and has a Master’s in cartooning from the Center for Cartoon Studies.

Design by Josh Kramer, with gratitude to Nathan Schneider.