#7: What Billboards Teach Us About Online Ads

+ Can Biden's bus tour go couch-surfing?

Welcome to the Civic Signals newsletter, a project dedicated to building better public digital spaces. If you’re already receiving this email, please share with your friends so we can build a bigger community.

On the road again

With the U.S. general election kicking into high gear this week, the 2020 presidential campaign offers online platforms a big chance to cash in with political advertising. In 2016, the campaigns and super PACs spent about $1.4 billion on digital ads during that election cycle. But with more scrutiny on how social media can spread political misinformation, different platforms are taking new steps at transparency this time around.

Just this week, Reddit announced a new subreddit for tracking key information about its political ads. It is a similar approach to Facebook’s Ad Library, while Twitter has opted to ban political ads entirely for the 2020 election. The challenge to create transparency in political ads requires rethinking how ads more generally get targeted on these sites. Along with the potential for misinformation, these ads are part of the challenge with the attention economy, which treats human attention as a scarce commodity to harness and monetize.

The problem of distraction, commercial interest, and public space isn’t new; cities have tangled with the intrusion of advertising for centuries, from bold business claims on the side of buildings to swinging shop signs above pedestrian walkways. But with the invention of the automobile came the spread of billboard signs and neon lights that drew greater attention.

While cities in the United States have contended with limiting billboards as far back as 1909, these eye-catching broadsides came into national focus as the interstate highways drew in a land rush in the 1960s. Writing for Life in 1959, urbanist William Holly Whyte wrote the first story in the magazine to use the term “urban sprawl” and described the consequences of uncontrolled suburban expansion into the countryside. As bulldozers gave rise to subdivisions, Whyte lamented the mess left by land speculation:

What open space remains you can no longer see. To the eye it is all a jumble, an endless succession of driving ranges, open-air theaters, billboards, neon signs, frozen custard spas, TV aerials and pink plaster flamingos.

As population growth kicked the federal highway program into gear, Whyte described these roadside attractions as a “foretaste of the future.” Such crass commercialization couldn’t continue, Whyte thought: “Your instincts will tell you that anything that looks this terrible cannot be good economics.”

The design of neon signs underwent a critical reevaluation in Learning from Las Vegas (1972) (Photo by Al R/Flickr/Creative Commons)

But the problem continued to a point where the federal government sought to intervene. In 1964, Lady Bird Johnson urged President Lyndon Johnson to write a Highway Beautification Act, after her frustration with the number of billboards and junkyards she used to see on her trips from Texas to Washington. Congress passed the bill in 1965.

At that time, the law was concerned with the physical space obstructed by the ads, rather than their content, as this current concern about political ads raises. But still the structure of ads shapes the web. If you remember banner ads, pop-up ads, email spam, or even the old rush you used to feel from push notifications, then you know how we’ve learned to ignore or block these roadside attractions of the internet. But advertising has been core to the business of the “information superhighway,” and now it almost has to find its way into the virtual road for us to see it. It makes it all the more important to distinguish advertisements from the other guiding information we’re consuming online.

A similar indifference to billboards and signs along the road existed back then, too. When Life went to document the federal beautification project’s effect five years later in 1970, everyday people didn’t seem to mind their intrusion and the roads gave way to novelty. “Nobody we met seemed to care much about the problem,” wrote Life editor Ralph Graves. “They didn’t even seem to notice.” (h/t Places Journal) With ads on the internet, getting people to notice what they’re being sold remains a civic challenge.

What’s clicking

Facebook will alert people who have interacted with coronavirus misinformation - Washington Post

What Zoom backgrounds say about our quarantined lives - Curbed

Apple and Google make a smartphone tool to track COVID-19 - NPR

The coronavirus traffic bump to news sites is pretty much over already - Nieman Lab

YouTube launches a free, DIY tool for businesses in need of short ads - TechCrunch

How Medium became the best and worst place for coronavirus news - The Verge

The news is making people anxious. Here’s what people are reading instead. - New York Times

All I need in life is this Facebook group where everyone pretends to be ants - The Verge

Quoteworthy

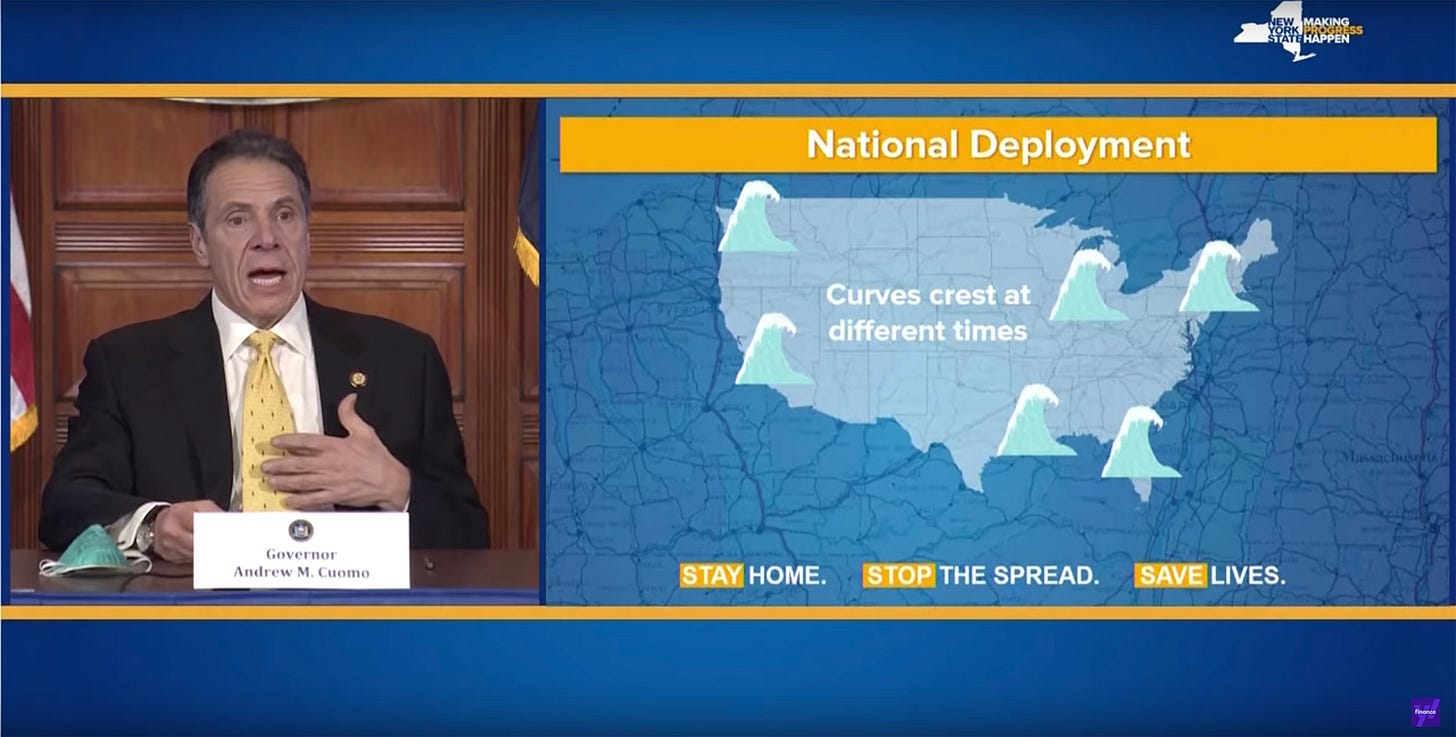

Another headlined “What Happens” prompts Cuomo to note, in Proxima Nova, that the “Bigger Question to Me” is “WHAT DO WE LEARN ABOUT OURSELVES?”

The lessons we might derive from such introspection are framed, in part, by the mix of civic symbols encountered in these briefings: Richardson’s excess and Microsoft’s functionalism, regal hues and high-contrast blue and gold, state flags and clip art, velvet curtains and polo shirts, chandeliers and LCD projectors.

-Shannon Mattern, “Andrew Cuomo’s COVID-19 Briefings Draw on the Persuasive Authority of PowerPoint,” Art in America

Digital handshakes

Speaking of campaign season, now that Joe Biden is the presumptive Democratic nominee, his “old-school retail” political style faces the daunting task of crafting an “all-digital campaign strategy.” Biden’s digital director describes the shift to the New York Times as a “battle for the soul of the internet.” By many metrics, from video views and podcast rankings to ad reach and post interactions, Biden’s campaign is lagging behind President Trump’s engagement numbers as the internet tends to amplify content that stirs emotions. That, Kevin Roose writes, has rendered Biden “invisible on platforms where conflict equals clicks.”

Certainly that means Biden will start to bring the fight to Trump directly, but it’s also a question about how to turn the kinder, less sensational qualities of politics into online media. What would it look like to turn the bus tour into a living room tour? Can Biden finesse his Onion-generated Diamond Joe meme image into an earnest door-knocking, couch-surfing campaign?

The template for more neighborly and empathetic campaign could take some cues from John Krasinski’s soft-hearted quarantine-counter-programming YouTube show, Some Good News. Or perhaps the Biden campaign could emulate the example set by Bernie Sanders in trying new formats like Instagram Live with Cardi B? Could Joe go crashing Zoom happy hours with Elizabeth Warren?

Send us your thoughts on what novel ideas you would like to see on the virtual campaign trail at civicsignals@gmail.com.

Be careful out there,

Civic Signals is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America. Share this newsletter with your friends!