#10: Laptops on Blacktops

+ What words will we use to describe our new online habits after COVID-19?

Welcome to the Civic Signals newsletter, a project dedicated to building better public digital spaces. If you’re already receiving this email, please share with your friends so we can build a bigger community.

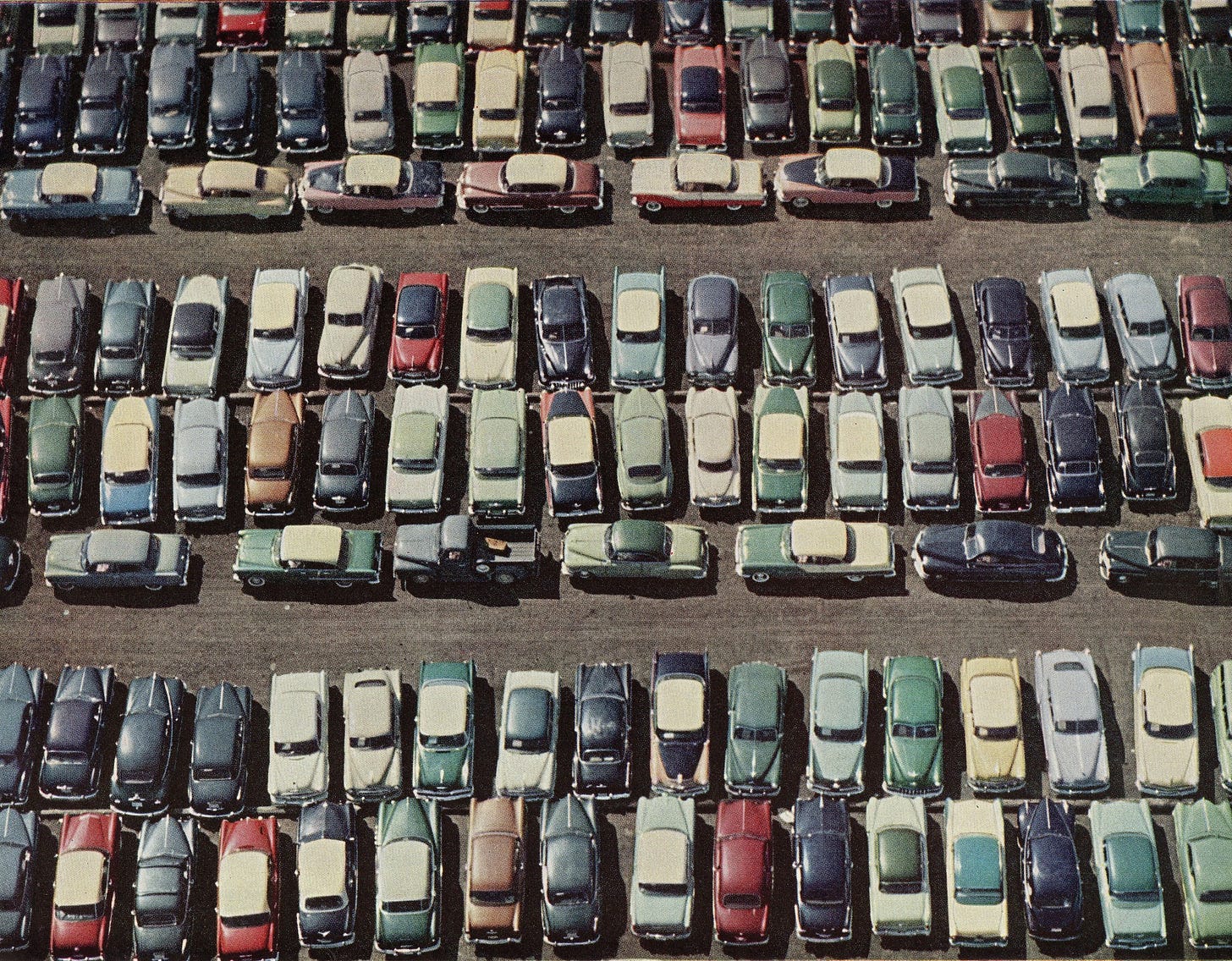

Remote lots

(Photo credit: Alden Jewell/Flickr)

America’s digital divide has long dampened the internet’s ability to offer equalizing opportunities in education and work, with about one in four Americans lacking access to high-speed internet at home. Now, with people being asked to work or take classes from home, the coronavirus lockdown reveals this societal inequality in a new physical form: parking.

With cafes and libraries closed, the parking lots near places with free Wi-Fi have become a “digital lifeline” for people, the New York Times reports. Whether due to a lack of broadband infrastructure or a lack of affordable options, limited internet access is a challenge both rural and urban communities face.

New polling from the Pew Research Center finds that 53 percent of Americans considered internet access “essential” during the lockdown—another 34 percent considered it “important, but not essential.” But only 37 percent of respondents told Pew that they think the government has a responsibility to provide broadband internet to ensure connectivity.

(Source: Pew Research Center)

There's an appropriate parallel here with parking, because for better or worse, parking has shaped the debate about what it means to have access to the city. Parking straddles the line between the public and the private, where the tradeoffs between paid parking lots or free parking spots shape how we reach the jobs and amenities that urban life offers. American planners have proven effective at building big highways that bring people into the city, but they have faced a challenge called the “last mile” problem, where that desire to get directly to your destination on the last leg of your trip runs up against the limited space available in a city that appeared limitless.

UCLA professor Donald Shoup has made a name for himself estimating the high costs of free parking, like longer commutes and higher rents. It’s this grey space of using public space for storing private cars that has made parking a key point of contention in arguments for bike lanes, public transit, and parks. And the challenge is that there are cultural and political concerns to navigate, rather than just building plans, to make these negotiations of the public realm successful.

The gaps in digital infrastructure mirror the gaps created by the built environment. But even once we’re online, the digital world replicate problems that are a matter of the expectations and biases once we are online and negotiating the rules that society has coded into using these tools. Take this example about remote learning from Naomi Klein in response to Governor Cuomo’s insinuation that technology could just replace the old model of a teachers in classrooms:

With so many city streets now going empty, it’s hard to miss how much of our desire to learn, work, and play has shifted to the internet. The fact that the United States’ internet has kept running during the pandemic, despite a 20 percent rise in traffic, is an amazing feat on its own, as Charles Fishman detailed in the Atlantic yesterday. But those parking lots filled with people trying to log on shows how the same issue of accessibility exists in virtual spaces. For once, it’s a real life avatar of those digital inequities, but it’s a haunting reminder that these barriers to entry online shape whose experiences we see reflected on our screens.

What’s clicking

With Zoom pranks, PowerPoint parties, and a billion memes, students are recreating campus life virtually - Slate

Should Google and Facebook have to pay the media? - OneZero

Mute your mic! Virtual city council is now in session - CityLab

Kids are staring at screens all day. Is this really a problem? - Elemental

The actual experience of virtual experiences - Vox

How we got to Sesame Street- New Yorker

What Google searches tell us about coronavirus fears - Recode

Yelp is making it easier for businesses to highlight virtual services - TechCrunch

Twitter tests a warning message that tells users to rethink offensive replies - The Verge

Word on the street

(Photo credit: Garry Knight/flickr)

How will we describe our new online habits developed during coronavirus like Zoom happy hours or FaceTime dates when we return back to spending time together in real life? For the New York Times, journalist Katie Mooney spoke with Gretchen McCulloch, the author of Because Internet, on how technology might influence our ever-expanding virus vernacular:

Looking ahead, linguistic changes are yet to come, Ms. McCulloch said. She explained the concept of a retronym — assigning a new name for a default now dated by technology or social change; for example, with the rise of cellphones, non-mobile phones became “landlines.”

“We are still in the phase of naming the new things we’re encountering, but eventually we’ll get to the stage where we need names for what things were like before the virus hit,” she said.

ICYMI: The Shift

Ordinarily, in a democratic society if the government starts to make decisions that don’t reflect some semblance of what people want, we have access to protest at the National Mall or the state house, or even afterwards in Zuccotti Park… The strange, worrisome thing is we’re in the midst of making these massive epoch defining decisions, and instead of those places, we have Facebook and Twitter and Zoom.

—Eric Klinenberg, Director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University

Don’t worry if you missed Tuesday’s livestream of The Shift, our new series exploring the social implications of the shift of public life to digital space during the COVID-19 pandemic (in partnership with NYU Institute for Public Knowledge, The Social Science Research Council, and The Knight Foundation), the video is available on YouTube.

In this episode, urban planner Toni Griffin, designer Chelina Odbert, and New York Public Library chief digital officer Tony Ageh weighed in with their takes on what makes public space important to civic life with Eric Klinenberg, Mona Sloane, and our own Eli Pariser. The Knight Foundation’s Gary Zamchick also illustrated throughout the discussion. The next episode of the series (date TBD) will cover how the crisis is shaking up education. We’ll keep you posted.

Logging off,

Andrew Small

Civic Signals is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America. Share this newsletter with your friends!