💾 Why we’re nostalgic for the early web

Also: A Ukrainian reflects on digital legacy and memorialization

This week:

👻 Revisiting the handmade quality of digital ghost signs from the early web

🎨 Beyond pixel art, people miss creativity, experimentation, and community

🪦 Denys Kulyk on how we remember the past using digital artifacts

Sometimes, you can spend all day on smoothly-designed interfaces like Airbnb, or spend an hour scrolling through perfectly manicured selfies on Instagram, and wonder to yourself, “was the Internet always this slick?”

You might remember that the web had a funky, weird adolescence that we love to write about here in this newsletter. In the mid-to-late 1990s, large numbers of people were online for the first time, and a new set of reliable protocols, browsers, and search engines made it easier than ever to find and build websites. Suddenly, anyone with a decent modem and a copy of “HTML for Dummies” could cobble together their own Dr. Who fanpage.

But there were limits, of course, both to image quality and size, as well as the sophistication of website design. Early websites often had a looser, messier aesthetic typified by pixelated images, manic animated gifs, and very basic typography. You can get a good sense for some of these sites by hovering over images and clicking through to some of the pages on Cameron’s World, a visual archive of deleted GeoCities content.

These websites, especially by today’s standards, required a lot of care. Before CMS backends like Wordpress, code was typed out — or copied and pasted from elsewhere — and then tweaked and adjusted continuously. It seems quaint to not just post something, but to revisit it later and make changes. Even the term “webmaster” sounds incredibly archaic today. From the way we communicate, to even the way we connect to the internet, our contemporary online lives are far more mediated by a few centralized, large corporations.

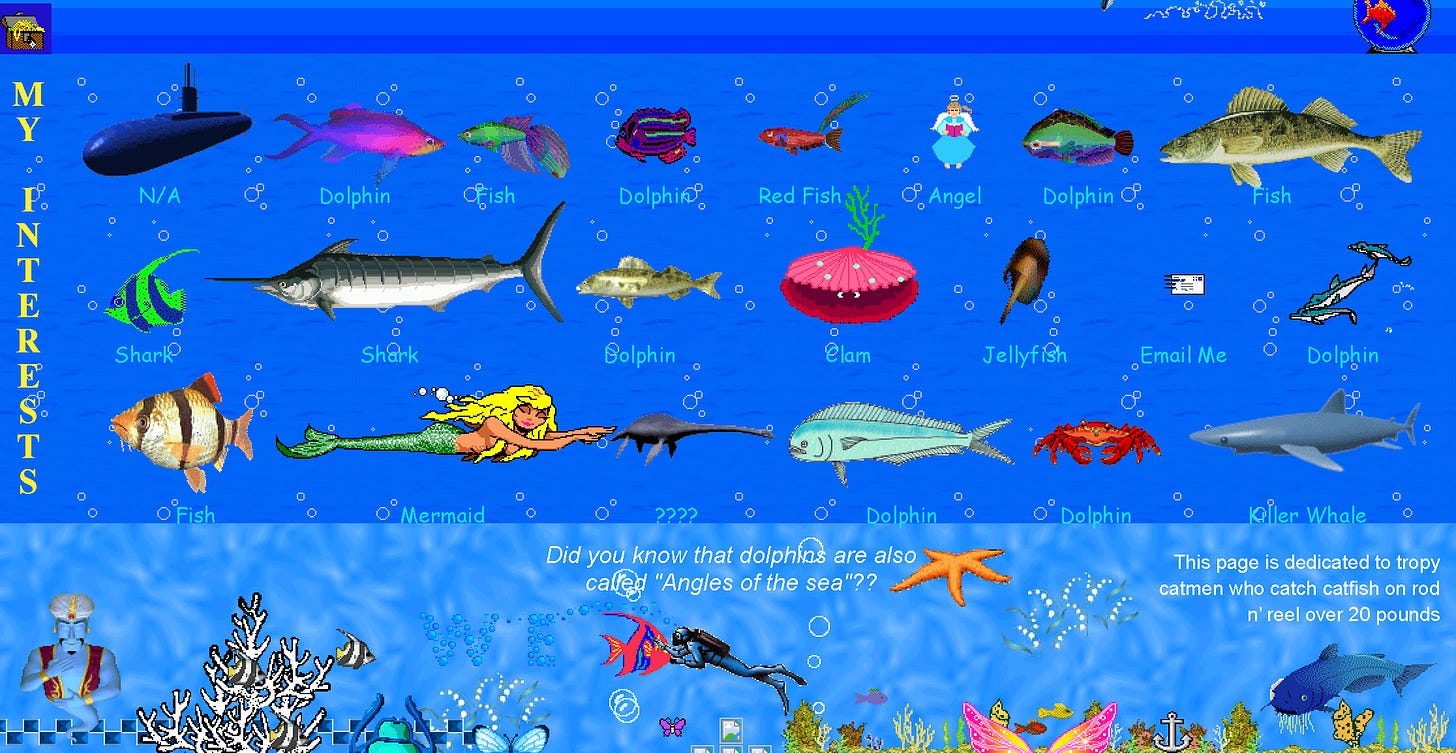

Painted signs with unfinished business

The boom and bust cycle of early websites reminds me of another medium for highly ornamental mass-communication and display: hand-painted signs on buildings. Just like early websites, painted signs were precipitated by large-scale societal changes. In CityLab, Feargus O'Sullivan explains how literacy led to the proliferation of painted signs in England:

As Britain developed as an industrial and imperial power throughout the 19th century, the government realized it needed far higher levels of literacy in the workforce. It set about an educational drive that culminated in 1870 with an act of Parliament agreeing that the government would provide free elementary education to those who could not afford it. A steadily more literate public could then be more effectively wooed through writing, and wordier advertising proliferated across urban walls to attract customers during the Industrial Revolution’s second wave, when new manufacturers’ move from heavy industry to focus more on consumer goods produced an ever-expanding range of products and businesses.

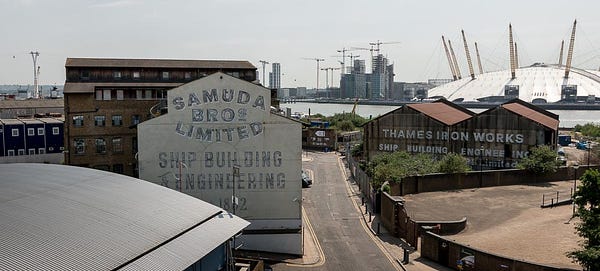

And just as the internet progressed to social media, blogs, and everything else, technological change also hastened the end for painted signs. Neon, plastic, vinyl were each cheaper and easier than hiring a trained professional to paint on a building’s facade. Yet today, all over the world, “ghost signs” persist.

A sign is a “ghost” when the original businesses is gone, but at least some of the sign remains. Faded and semi-legible painted signs can be found in many cities, and people delight in finding them and chronicling them with tags like #ghostsigns on social media. In some cases they are restored by professional painters, recreated with light projections, or even mimicked to add authenticity to a development project:

Digital ghost signs

And while a lot of the early internet has been wiped away, no longer hosted or adrift in a sea of dead links, plenty of it has been preserved intentionally. Thanks to groups like the GeoCities Research Institute and the Internet Archive, we can see, and sometimes interact with, long dead webpages.

There are also the small wonders like the original Space Jam website from 1996, recently moved from its original home at Spacejam.com to make space for the sequel, into a permanent URL here. Some of the subpages, like a list of radio stations where “Fly Life An Eagle” are playing, are so precious. The source code includes the charming snippet … <!-- Badda Bing, Badda Boom -->. Why are “digital ghost signs” like this appealing? Is it just fun to consider how incongruous they are with the rest of the internet? Or is there something more?

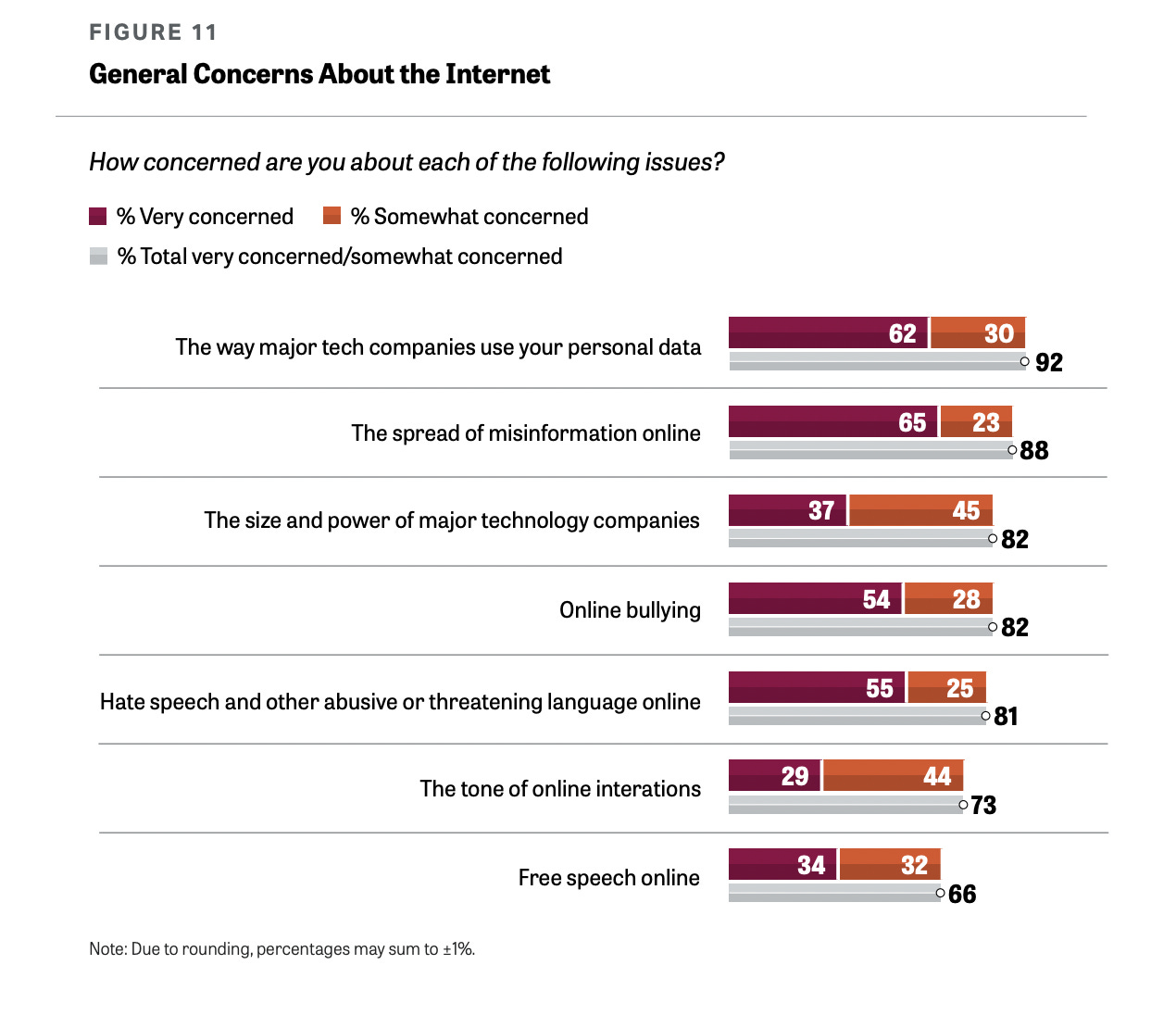

For New Yorker contributing editor Kyle Chayka, the appeal of the early-internet aesthetic is its contrast with the “repetitive templates, inhuman scale, and turbocharged content” of social media. “For many people, the earlier era of the Internet represents a time when they still had power over their digital lives,” writes Chayka. Unlike an HTML website where you can right click on the background and select “View Page Source” to review every creative decision, what we see on social media is powered by vastly complex “black box” algorithms. It’s often impossible for users to understand how social platforms work. Studies show that even though most people use social media, they have serious concerns about it.

But it’s not just about authorship and intent. In his newsletter, Chayka says the spirit of these sites was far more collaborative and community-minded: “what I miss most of all about the earlier internet is the sense that I was connecting to a coherent community, a group of people who, even if I didn’t know them IRL, I knew.”

Another moment of change?

Technology keeps on changing, and as we’ve discussed here many times before: it’s not at all inevitable that social media will continue to function in the same way. For a few reasons, this feels like a moment of instability and upheaval: TikTok has emerged relatively suddenly, with powerful in-app editing tools yielding content that feels comparatively raw and unmanipulated. This has resulted in a huge volume of creativity on the app, despite its deeply algorithmically-mediated feed. Also, cultural tastes may be shifting towards a new demand for authentic, hand-made digital experiences.

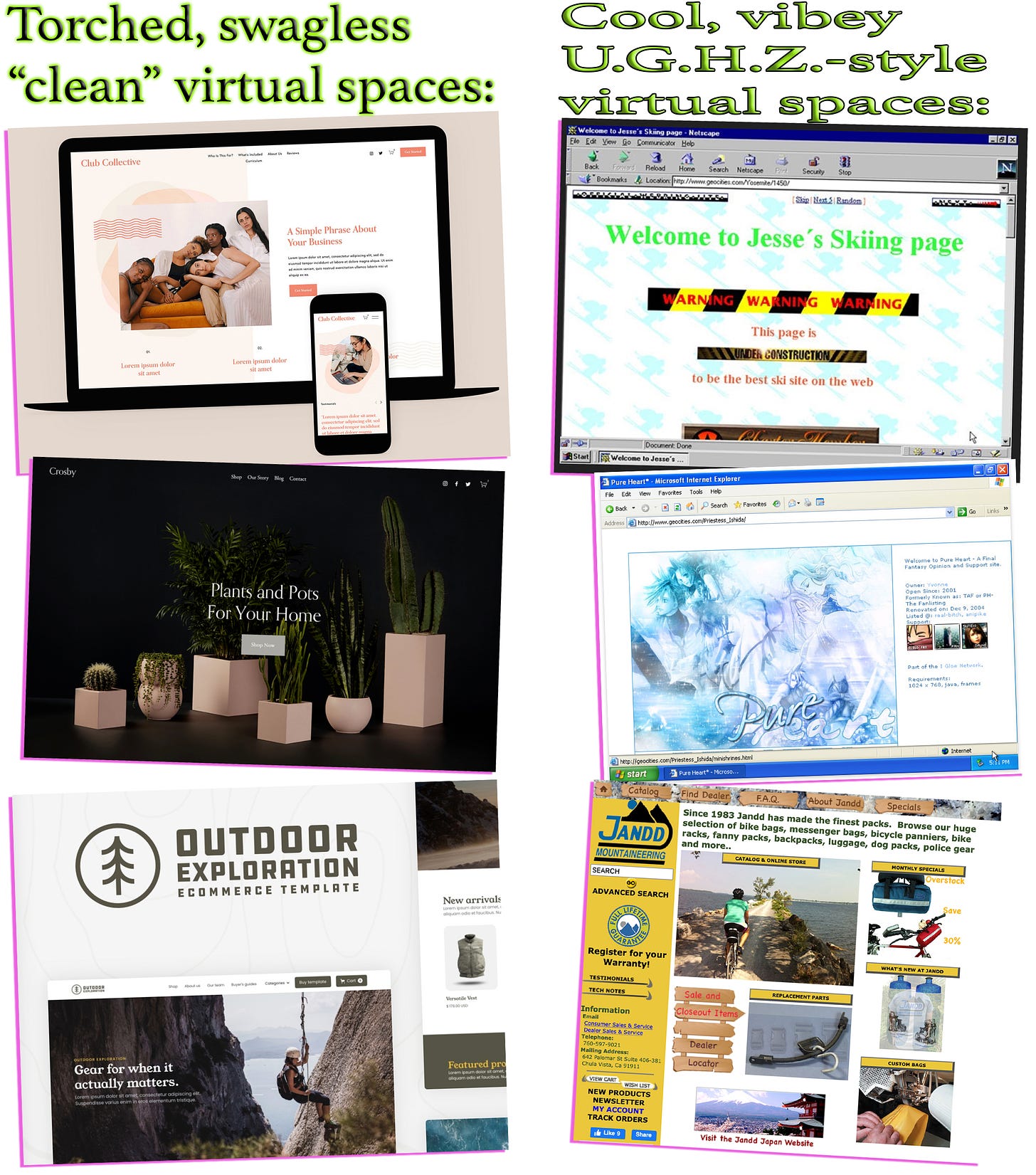

In the New Yorker, Chayka tracks the rise of pixel art and other “lo-fi digital aesthetics,” including a MySpace clone called SpaceHey popular with Gen Z, and the retro stylings of NFTs like CryptoPunks. Cool kid internet tastemakers Blackbird Spyplane recently coined the term “Un-Grammable Hang Zones (U.G.H.Z.)” for real life and virtual places that defy the “torched’” look of so many online brands, in favor of the “vibey” throwback style of hand-coded websites.

And yet, we can’t completely go back to a world of autoplaying background music, pixelated animations, and digital guest books. That’s all gone. And for the most part, I think the appeal of these pages has less to do with design and everything to do with the values of the era they’re from. One of things that’s so exciting about ghost signs is that they recall a time of professional artisans deeply interwoven with everyday culture and society. Many values of the early years of the internet, including openness, creativity, and connection, are deeply appealing now.

But while looking backwards for inspiration, let’s keep the accessibility and approachability of the modern internet we’ve built in the meantime. It’s good that websites and videos are easy to make, and that there are many tools for easy transcription and translation to accessible formats. So bring on the pixel art, as well as new protocols and platforms that make space for authentic, unmanipulated creativity.

It seems to me that many users are craving to be able to see and understand how the online content they consume reaches their screens. Is it just nostalgia for a less complicated life online, or the beginning of a social media version of the “farm to table” movement? Would you join it? What would you call it? Tell me in a comment:

– Josh

I started writing this article three months ago when the Russian invasion of Ukraine seemed like madness and we all refused to believe it. For more than two weeks now, my country has been fighting for freedom and the democratic ideals of the free world. Digital legacy has become a new normal as many of our friends and families no longer appear online and we can only keep digital records about them. I invite you to learn more about current events here. If you want to help, please donate to Come Back Alive, which helps Ukraine's Armed Forces to protect my nation. –Denys

Somewhere at home, you probably have a box full of memories: diplomas, pictures from concerts, a favorite jersey. Whether it’s a school yearbook or black and white pictures of relatives from a different country, physical objects have always been important to the way we create and maintain memories.

Good memories make us feel comfortable; they help us reflect and guide our actions. However, people now work online, nurture relationships on social media, invest money in digital assets like cryptocurrencies and NFTs — all without creating physical objects. As our digital and physical lives become more interconnected, we store memories in zeros and ones instead of printed photos, videotapes, and paper notes. Perhaps the way we make memories will have to change too. As we live more of our lives online, we'll need to find an equivalent for each of those physical objects in a digital setting.

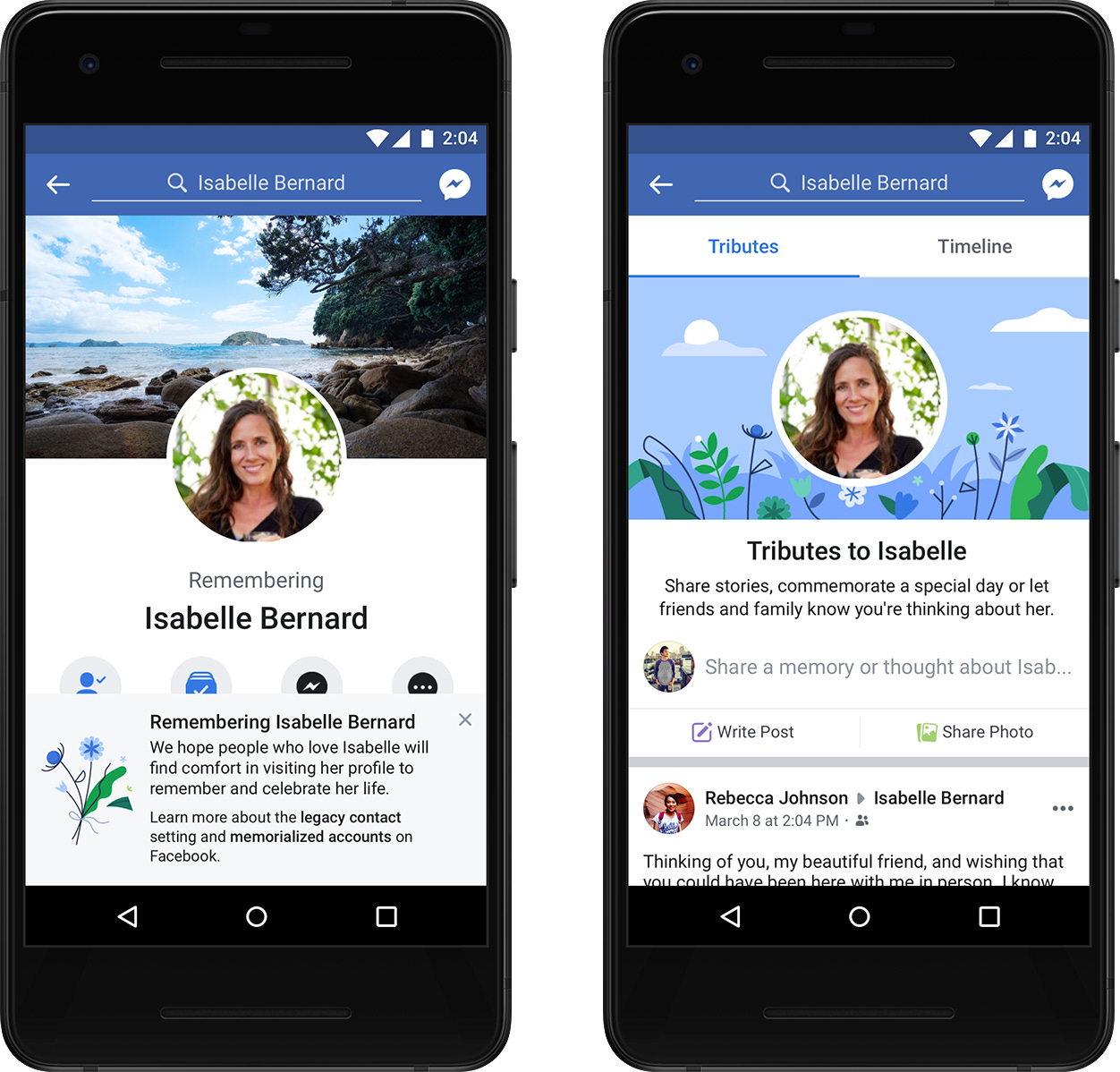

As the internet turns 30, there is far more death online. Many real-life connections emerge in the digital world: you might turn to a trusted friend from social media to become your emergency contact. Instead of a will, you might bequeath a password to share your iCloud and Google data. And increasingly, social media platforms are becoming digital cemeteries filled with memorialized accounts.

In real-world Ukraine, families go to cemeteries to grieve loved ones every year during the Easter holidays. One tradition is to bring bread and candies to leave near tombs for others to eat and to pay respect to deceased family members. I have attended a few of these events. It’s a big part of our culture to show respect for those who are no longer with us. More importantly, small talk at events like this can often lead to deeper discussions between family members that has helped me learn about my extended family.

What do we lose when a legacy goes online? We can pass down our favorite book, a guitar from a high school band, or even our house. But people often don't own their digital legacy: they rent storage from Google, Facebook, Apple, and other companies. You’re less likely to accidentally discover a relative’s memories while cleaning their attic if their memories are on their phone, locked behind a phone passcode. Future generations may never learn how their great-grandparents backpacked together across Europe and fell in love unless they wrote it down in a blog post and carefully saved a copy.

Of course, people will find social media profiles with nice pictures and announcements on their career changes. Yet, that’s not the same as handwritten, private love letters. A public social media profile will never match the intimacy of family-curated photo albums of awkward pictures from high school and family trips. Private text messages, including texted photos, can easily be deleted permanently when a user passes away. If the protocols of the internet change, to something more decentralized, perhaps on the blockchain, how will that affect access to memorialized accounts? It may take decades to build new norms, laws, and expectations about digital legacy so that digital memories can be preserved for future generations.

Denys Kulyk is interested in how people communicate and learn with technology. He is a Product Manager at Grammarly. Apart from work he also writes and illustrates a newsletter on how to have a healthy relationship with technology in the modern world.

Live in DC this Wednesday

Our friends at Garbage Day and All Tech is Human are taking part in a live tech festival and mixer in Washington, DC this Wednesday at Union Stage. I’ll be there if you want to come and say “Hi.” There will be “fireside chats, live podcast tapings, panels, and speakers exploring the most critical questions about our relationship with technology, and where we go from here.” Speakers include The Intercept’s DC Bureau Chief Ryan Grim and The Young Turks’ Jordan Uhl. Use promo code FUTURE for $5 off! Click here to check it out.

–Josh

Badda Bing, Badda Boom,

Josh

Screenshots with lots of gifs are from Cameron’s World. “Digital Legacy” illustration by Denys Kulyk. Facebook memorial image from Meta. Our Connected Future illustration from Digital Void.

New_ Public is a partnership between the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas, Austin, and the National Conference on Citizenship, and was incubated by New America.