Starting today, Civic Signals is becoming New_ Public: a magazine, a newsletter and a community for all who believe our society needs digital public spaces 🏞📲. A movement is growing around the desire for online spaces that serve us, together: a public. And we want to support it by telling better stories about what public-friendly design might look like, by showing you glimpses of the work that’s already begun by kindred partners all over the world, and by connecting the people who can get us there.

In short: we want to make space for new ideas about what the internet can be.

With this launch comes some exciting new changes:

Marina Garcia-Vasquez, who has led a number of visionary media projects at Vice, the Wall Street Journal, and other institutions, joins us as Editor-in-Chief of New_ Public. Marina’s projects have covered technology, art and culture from deeply intersectional perspectives. You will be hearing much more from her in the weeks to come.

We’ve also recruited an all-star group of editorial contributors—Meredith Clark, journalist and Assistant Professor in Media Studies at the University of Virginia; Malkia Devich-Cyril, activist, writer and Senior Fellow at MediaJustice; Dipayan Ghosh, co-director of the Platform Accountability Project at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School; Sara Hendren, artist, design researcher, writer and Associate Professor at Olin College of Engineering (she’s the reason your phone has a ♿️ emoji); Aleks Krotoski, broadcast journalist, author and academic; Vanessa Mason, “Belongingness” expert and research director at the Institute for the Future; Margarita Noriega, co-founder of Glimmer and VP of Engagement for CalMatters; Doug Rushkoff, media theorist and author; Kamal Sinclair, Executive Director of the Guild of Future Architects; Caroline Sinders, machine-learning-design researcher and artist; Astra Taylor, documentary filmmaker, author of The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age—to contribute their unique perspectives and wealth of knowledge to the project.

And we are enlisting you, our dear readers—and now accomplices in publicness.

Here’s what you can expect to see in this space:

📰 A digest of the latest & greatest in the public-spirited tech space not being covered by mainstream tech journalism

💁♀️ Inside stories about new products and ✨speculative projects✨ that reflect this ethos from members of this community and beyond

✉️ Invitations to special conversations and events for this community in pop-up spaces

📚 We’ll be unveiling our “signals” research and framework about the key qualities of public space created with global cross-disciplinary experts and superusers

🗣️ Conversations with product managers, design activists, urban thinkers, academics and more

⛏️ Throughout all this, we’re hoping to break down the barriers of a typical newsletter, so that we may see and get to know each other. How can we help you?

In fact: tell us how we can help you 👇

🎞 Why digital public spaces?

Through the dozens of conversations we have been having over the past two years, what’s become clear to us is that our public spaces have a lot to teach us (good and bad!) about how to build spaces that promote the kinds of social behaviors that can help cultivate a more flourishing society. Taking a page from Vancouver Parks: “The space between us will hold us together” (h/t Wendy HK Chun).

We’ve been waiting to share this beautiful video made in collaboration with filmmaker Sai Selvarajan, which tells the story of this project, where it comes from and where it hopes to go.

🏙️ What does your favorite public space mean to you?

We found these vignettes from Marina and our founding contributing editors really engrossing and we hope that you will too.

_Marina Garcia-Vasquez

One of my favorite places in this world is El Jardín in the historical and architecturally rich town of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. As a public space, El Jardín is the most central tree-lined park in town and an active meeting zone. One could park themselves on a bench and read a book in the sunshine, exchange pleasantries with passing neighbors, check out the fashion of tourists from Mexico City, perk an ear out for an American accent, or watch the religious and cultural festivities that occur within the neo-gothic church or parroquia across the way. Your senses are stirred by the sound of traveling musicians singing ballads, the smell of local delicacies sold by street vendors, and the sight of children playing on cobblestone streets. The reward of posting up in the plaza for hours at a time is the exchange of local news and the visual cues of culture happening right before your eyes. You are in the heart of a bubbling picturesque Mexican village.

As a young adult who traveled to Mexico before the proliferation of smartphones, El Jardín was an easy place to catch friends after dinner to verbally find out about an art gallery opening or local house party. Today, as with many plazas around the world, El Jardín continues to be the buzzing point of entry into the town’s local culture, a barometer of the town’s energy, and a majestic place of beauty. It is a true place of gathering, connection, and community.

_Sara Hendren

It took me several months of living in Los Angeles in the late 1990s to figure out that I had rented an apartment, purely by happenstance, at the base of Runyon Canyon—a small series of dusty public hiking paths that take you high up above the city, the low trees and scrubby bushes making for wide vistas in every direction. My husband and I had landed in LA from Boston, blinking slowly in its “air light,” as Lawrence Weschler called it, and it had never occurred to us that a public park might look like that, might make a real hike possible—simple, even—in the middle of the city. What a find! Within a few months of that discovery, when a stray dog landed in our laps thanks to a neighbor, that park became not just our daily walk but twice-daily.

I came to count on those paths for their natural round-trip completion: a series of linear loops, none too long to get lost in, none too short for an unsatisfying zig there, zag back. Those loops took on a shape that I thought of as a narrative mirror, a walk to represent whatever furrowed-brow problem I was working on then. I huffed it out on the trail, up to the top, facing down some internal conflict, till I was completely out of breath. And then, right on time, I got the denouement of return, down the mountain with some slightly altered perspective. Public spaces are most compelling when their uses take on different meanings in different stages of your life, and that park will always represent that time, my late twenties, now lost. I’ve wanted other things from public parks in different stages since then—two decades later, with three kids, back in Boston, and a brand new puppy. But recalling the time of those LA canyons will always cause me a little bit of ache.

_Aleks Krotoski

At the moment, as a recent transplant to New York City, I am enchanted with the city’s streets. I’m buzzing on the smash of people, the collection of everyoneness condensed into pavement-width walkways and storefront escapes. We moved here from Los Angeles, where the public space of the beach never really did it for me—too empty, too open, too impressed with itself. I am a passionate lover of nature, but I have to retreat from its awesome vistas to the smothering city, where you trip over ideas and inspiration when you step out the door.

I only recently realised how important this public space is to my mental health. I don’t need to live here; I have no business here. My work is far away and it always has been, wherever I am. I have always been liberated from place, like my former neighbours who are newly remote workers and schoolers, and who have now moved to the suburbs “because they can”. But my previous experiments of remote working have taught me that this Jane becomes a very dull girl without immediate external stimulation away from the phone or the computer screen. And here it is, outside the door, all the world to watch and see. Conversations struck up in the line at the fishmongers. Stories with the lady who’s lived down the block for forty years. A fight on the corner. A man with bubbles trailed by a pack of kids like a sudsy Pied Piper.

It’s the rhythm of the chaos that inspires me. Rhythm that emerges like organic matter. Chaos made possible by the public-ness of the thruways. Other cities have it too. They’re usually the old ones. The ones that have drawn people to them with promises of anonymity, new life, reinvention. They have old ways of doing things, hidden networks that police the tide. To uncover these secret passageways, you need to find a place to sit, and watch the public rolling by.

_Vanessa Mason

I love the murals and public art of Johannesburg that I saw on a solo trip there four years ago. Just before the trip, I rediscovered a love of photography that really encouraged me to spend more time in public spaces and see the world in new ways.

So much of the city occupies multiple moments in time, with murals depicting the violence and struggle of apartheid as well as the unbridled creativity of Black South Africans.

As you walk about, you also see how the changes in the built environment shape the messages the artist hoped to convey in their work. It’s also a wonderful way to meet other people who are gazing at the art work. In so many ways, the art and the people you encounter there serve as a visceral reminder of how much more we have in common than discourse would imply.

Like many people, I have spent much more time in nature due to the COVID19 pandemic. I love feeling connected to our public parks and nature, but I miss the awe that comes with seeing the work of human hands in public art and the feeling of being energized and inspired that comes with “bumping” into people there. In our social distanced reality, we don’t have the same kind of engagement with art and creative expression. Unlike museums, public art makes human genius available for everyone and helps to fulfill the right to the pursuit of happiness promised in the Declaration of Independence.

_Margarita Noriega

My favorite public space is the Mariposa Grove in California because it is the home of the most special thing in the world to me. I’ve never been more in awe of anything than of the Giant Sequoia, also known as Sierra Redwoods—an icon of what connects life across millennia. Standing among them, things make more sense to me—a truly rare experience. Its size makes sense for how big (I think) the universe is. My height makes more sense because I’m not that tall, or short, after all, and who cares? The moon and stars feel closer to me because I know the top of a giant sequoia is a little bit closer to them.

If you are next to one, you are literally standing on the shoulders of giants. (For the record—don’t hug them, as I excitedly and foolishly did years ago—their root system is sensitive to being stepped on, and whose isn’t, honestly?) The oldest known giant sequoias are about 3,000 years old, which makes me not 36 years old but 2,964 years young.

The giant sequoia inspire me to dream bigger than the scale I live in, to acknowledge that everything in the world is living within its own scale, and dare to suggest that every place is some one or some thing’s public space, and it is my obligation and promise to honor that beautiful, sensible, ancient fact.

_Eli Pariser

For my family, Fort Greene park, a 30-acre square of elm trees, winding paths, playgrounds and monuments, has been a very special public space. It’s an early-morning romper room, mid-day meeting point, festival ground and farmstand, as well as a spot to sit for an hour on a hot summer evening.

There are house-music dance parties, movie nights on the grass, soccer games during which you can hear cursing in at least five languages, and, of course, the world-famous Great Pupkin Halloween Dog Costume Contest. On some evenings, the park feels like an ode to democracy itself.

In Fort Greene Park, this process—the building of a collective identity, the weaving of a social fabric, the identification and remediation of inequities -- is ongoing, and it’s not always relaxed or comfortable. Friction and suboptimization are part of the essence of public space. What makes public spaces so generative is precisely that we run into people we’d normally avoid, encounter events we’d never expect, and have to negotiate with other groups that have their own needs.

Great public spaces can’t be separated from the fact that they’re owned by everyone and therefore ought to be designed for everyone. As Jane Jacobs, a lioness of public life, wrote, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” Community board meetings and public governance processes can be slow and annoying and very frictional. But—when they’re working properly—they force designers to contend with and listen to the communities they ostensibly serve.

_Douglas Rushkoff

I think my favorite public space has always been the library. I remember going to the Larchmont Public Library when I was maybe 5 years old. And they had a separate entrance for kids, to a whole library in the basement.

I don’t know if I liked books any more than the next kid. But I was amazed that there was this whole place with books that were already paid for. My mom didn’t have to buy them for me. They were just there. And I remember the lady there—the librarian—telling me I could take home any book I wanted for two weeks. Up to FIVE.

So we signed me up for a library card. They were filled out by hand or a typewriter in those days. It wasn’t something you applied for and then came in the mail from some central office. They handed it to you on the spot.

It was my first introduction to the word “public.” Public Library. And it really framed my understanding of public space, public projects, and the whole public ethos. People paid for this place and all the books in it, because they thought it was an important public good. Not just for themselves, but for all the kids downstairs who don’t even pay taxes.

_Kamal Sinclair

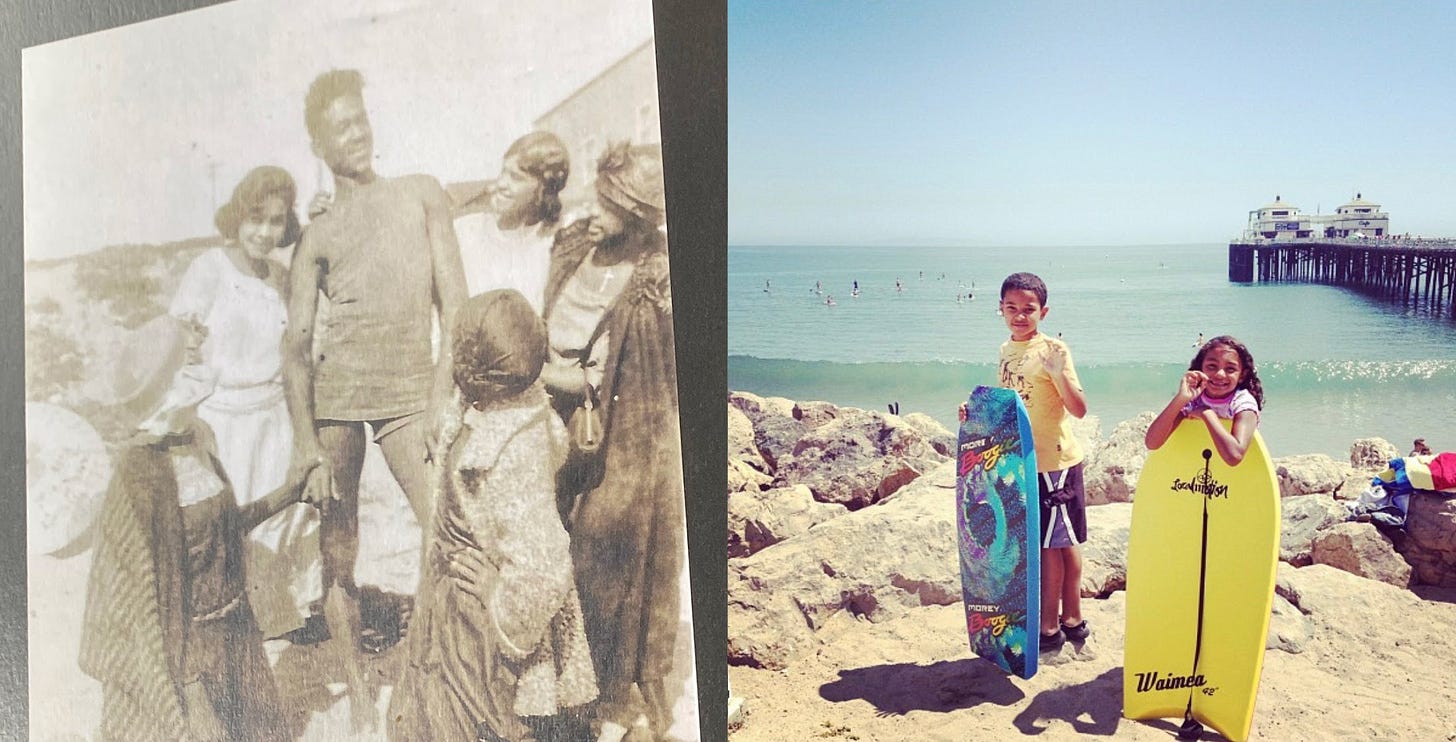

My family and I are multi-generational Angelenos, which translates to residents of the Los Angeles area. Our ancestors migrated from the southern states to this area in the mid-1800s, before the emancipation proclamation. After being freed by the person who legally owned them as slaves they settled in Watts, CA and built a farm house. In fact we have a picture of our last living family member that was born a slave standing in front of that house in 1963. In that same photo album we have an image of family members posing in their swim suits at an LA beach in 1919. You can look at the history of sites like Bruce’s Beach or the advocacy of the California Coastal Act to better understand that Beaches in California have been historical hotspots for the battle between exclusionary access for the privileged and inclusionary access for all. When my family and I go to spend a day at a public beach in LA, enjoying the views of the vast sunlight ocean in one direction and the mountain cliffs in the other direction, I think about those who have championed free and open access to these natural wonders.

_Caroline Sinders

Two things unite New York and New Orleans in this specific memory, other than nostalgia. Okoay, three things including nostalgia—which is live music, and live music and colorful characters in two parks both named Washington Square. I visited New York City when I was 13 years old, and visited Washington Square Park. Walking through the arch right to the fountains, I heard live jazz music. I saw old men placing chess, and crisscrossed across the park, passing NYU students who were delightfully dressed—peacocking all around, with bright colors, or in all black. It was so cool.

Washington Square park in New Orleans is right off Frenchmen Street, which comes alive, with music, at night. Almost every storefront on that street is a bar and music venue. The street itself gets packed shoulder to shoulder with people, holding cold drinks, and dancing in the street. And the most perfect respite from the music, but you can still hear it? Washington Square Park, which is also open during the day.

The beauty of a public space is just that—it’s public, for the people. It allows for a kind of unbridled happenstance, of what joy and relaxing. Unlike other spaces that can feel public, but aren’t really, a park is. It’s localized, and reflects the DNA of that community. Only few of our digital commons spaces do that (and definitely not the ones that are created by Big Tech). A public space should reflect the neighborhood—their wants, needs, and their joy. What is a public space without joy, or music? I can’t say, and I don’t want to know. That’s the beauty of parks—those perfect public spaces, free, but full. Sometimes all you want to do is sit, and be, and be with friends, and music. Anything can happen in a park. Parks that are filled with the orchestra of murmured conversations, the thunder of laughter and live music, of drums, dogs barking, and dancing. Washington Square Park(s), in either location, are magical spaces in my heart.

💬 Introduce yourself

To kick off New_ Public, we’re asking our community members to introduce themselves. What’s your own favorite public space, and why does it matter to you? Is there a way to translate some of those elements into digital spaces? Reply in the comments below, or share it on Twitter with the hashtag #WeAreNew_Public.

Just Around the Corner

There’s so much more than we can fit into this issue, so don’t forget to visit us at newpublic.org where you’ll find our editorial values and a sneak peek at the immersive and participatory festival we’re hosting on Jan. 12-14th, 2021.

We’re looking forward to seeing all our friends together in one place.

Finally, who’s the one designer, urbanist, technologist, builder, artist or civic futurist that you think should be part of New_ Public moving forward? Would you consider sharing this with them?

All dressed up and someplace to go,

The New_ Public Team

With the pandemic, I've been drawn to the overgrown, in-between spaces that interlace my Boston neighborhood. The most enriching of these has been Allandale Woods, a "small urban wild"—so designated by the Parks Commission—where a tangle of trees fills up a series of modest glacier-inscribed valleys, which lie like a bit too much carpet rumpling up between the busy parkways.

It's a feral place, bottle-glass strewn and New-England gritty, stands of slender glowing beeches on the hillsides giving way to reed-choked seeps and brookside jewelweed thickets, remnant blueberry barrens haunting the hilltops. An island of green in the city's hardscape sea, it lacks the native-vegetative richness of big woodlands to the west, but is constellated with the cosmopolitan traces of invasives and exotics—like the twisty little larches near the parking lot, fugitives from the nearby arboretum, who are just now giving up their golden needles as autumn gives way to winter.

My dog, herself the color of November oak leaves, porpoises through the drifting litter, chasing whatever windmills are tenanted by squirrels; my senses hitch a ride as she blurs through the whiplash undergrowth. I know this is a place of invisibilities, too, of uneven access (fringed by pricy townhouse estates, the nearest bus stop a long out-of-woods walk away). It's a place of past trauma, too—the land having once been a private estate and, before that, a parcel of farms deeded to the Weld family by Governor Winthrop, a prize for having fought the Wampanoag who lived here. Stripped of trees and tilled for corn and tobacco, this land would have been worked by slaves, African and Native, before slavery was finally outlawed in Massachusetts in 1783. So this public space, in its feral richness and gritty diversity, also holds wounds and secrets—some lost to time, others ongoing—a condition I suspect no space, digital or otherwise, avoids entirely. How we walk them, how we witness, makes the difference.